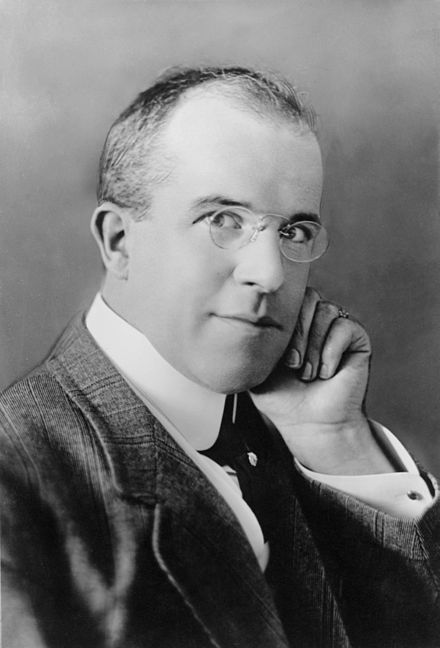

James Stuart Blackton (1875-1941)

James Stuart Blackton (1875-1941)

Another Englishman who can be truly said to be one of the godfathers of animation, Blackton produced most of his work in the USA, so may erroneously sometimes be considered an American animator, but he was born in Sheffield in England. He worked with Thomas Edison and set up the American Vitagraph Company, one of the first motion picture companies in America. Eventually the company was bought out by Warner Bros. Blackton produced some animated films that are recognised today as the finest examples of clever stop-motion film, including “The Enchanted Drawing” (1900) in which Blackton draws a picture of a fat man and then beside him a bottle and a glass. He then takes the glass and bottle from the canvas and drinks the beer, later also drawing a top hat on the man which he takes and wears. The expression of the drawing changes too. It’s really quite remarkable for the time.

His other major stop-motion films (not strictly animation but using it in some scenes) are “Humorous Phases of Funny Faces” (1906) and “The Haunted Hotel” (1907), both of which illustrate the technique well, especially the latter, which allows the creation of ghosts on the screen. “Humorous Phases” shows two faces, one man one woman, reacting to each other, They smile, wink, and when the man blows cigar smoke at the woman and obscures her completely (just before she makes a disapproving frown) Blackton erases them both and creates a new, full-figure sketch of man who bears more than a passing resemblance to a certain rotund director of suspense films! Good evening…

“Haunted Hotel” seems to show ghosts writhing in the smoke from the chimney as the short opens, then the house and a tree outside it both animate, the windows and doors of the former becoming a face. Inside the hotel, objects move, confusing and annoying the weary traveller, and then in an action which surely Disney must have robbed for Fantasia twenty years later, bread cuts itself and coffee pours itself out and then a sheet runs comes out of the milk jug and dances around. The animation is exceptionally smooth and seamless for the era we’re talking about here, and it’s no wonder all of these early films are now in the Library of Congress, preserved for future generations.

So, far from Uncle Walt or even already-discussed and rightly celebrated Winsor McCay being the father of animation, it seems the only ones to come close to deserving that title were in fact English. Still, everything the abovementioned created was either what were known as “lightning sketches” (where the hand of the artist is shown sketching out a figure which is then animated by various cinematographic effects) or stop-motion films, both of which can certainly be regarded as forms of animation, but don’t really tie in with what cartoons and animated films would eventually turn out to be, ie manipulation of frames of drawn characters.

Over the English Channel, the film craze had already been underway of course, with Reynauld and the Lumiere brothers, but nobody had really made the leap into true animation. It was in fact another Frenchman, decoding the ideas and methods of an Englishman, who would perhaps unlock the door that led to one of the world’s first true animated films.

Émile Cohl (1857-1938)

Émile Cohl (1857-1938)

Cohl was intrigued by the process used to animate the dinner things in James Blackton’s “The Haunted Hotel”, and set about working it out for himself. Once he had, he used that process to produce his own animated feature, which debuted in 1909. “Fantasmagorie” featured a clown who interacts with various other people and objects. The motion is fluid, and when a woman sits in front of him with a large hat with many feathers, blocking his view, he delights in taking the feathers from her hat one by one and disposing of them. But the film is very stream-of-consciousness, as figures become other figures, objects metamorphose and really there’s no real sense or logic to the thing, unlike just about every other animated feature prior to its creation. At one point, the animator (Cohl) seems to actually reach into the drawing and pick up the character.

This was totally different to anything that had gone before. Up to now, any animated feature, no matter how weird, had a strange sense of logic running through it. Paul’s car flew in “The ? Motorist”, yes, but it still followed some basic rules of logic, driving around the rings of Saturn, using the clouds as if they were hills. Despite the need to suspend disbelief, this and other animations still kept their feet, metaphorically speaking, rooted on the ground. Weird and unexpected things happened, yes, but you understand what was going on. In “Fantasmagorie”, as the title implies, everything is a fantasy and nothing is, or needs to be, explained.

This is perhaps the first template for the true cartoon, where things just happened, and no laws of physics applied. A wall could fall on a character, squashing him flat, but he would be up and running about in the next scene. People could fall from heights and leave with nothing more than perhaps concertinaed up legs (which would be staightened out next time) and characters could be shown dying, but still remain alive. In cartoons, everything would go, nothing would be too nonsensical or fantastic or unbelievable. Everything was possible, everything was doable, and there was no such word as can’t.

Three years later, Cohl animated “The Newlyweds”, a comic strip that had appeared in “New York World” , which I believe makes him the first to bring characters who had appeared in a newspaper strip to life, as it were, through the medium of animation. Only one example of this long-running series has survived time’s passage. You can see it below, but be warned: even restored, it’s still pretty poor quality.

It’s believed that later animator Winsor McCay took some influences and perhaps even paid homage to Cohl in his films, particularly “Little Nemo”, created a year later in 1910. Another ground-breaking film by Cohl introduced colour (I can’t confirm if this was the first time or not that colour was used in an animated film - other than coloured paper, which was of course in use long before this - but I haven’t read of any other instances of it) to allow him to animate coloured blank canvasses in the four-minute live-action film “The Neo-Impressionistic Painter”, where a prospective client is duped into thinking that blank slates are works of art, his imagination filling in the details which Cohl draws and animates.

George Méliès (1861-1938)

George Méliès (1861-1938)

Yes, I know what you’re thinking. You

are thinking it, aren’t you? You’re right: he died the very same year as Emile Cohl, mere hours later in fact. Seems the history of animation is full of such crazy little coincidences. But who does not know this name? If you don’t actually know his name, you definitely know, or have seen clips of, what was believed to be the world’s first ever science-fiction film, “A Trip to the Moon”, based on fellow Frenchman’s classic novels “From the Earth to the Moon” and “Around the Moon”. Having had his interest in cinema fired by witnessing the demonstration of the Lumière brothers’ new invention in 1895, he to buy one but was turned down. However two years later their camera and others were readily on sale and he was able to buy one that suited his needs.

One of his earliest films used the effect of multiple exposure to allow him play seven characters at once in the 1900 short, “One Man Band”, while “The Vanishing Lady”, even earlier (1896) shows him making a woman disappear, come back as a skeleton and finally as herself. All of these effects of course are more trick film techniques, and perhaps are not, or should not, be considered true animation, but it’s hard to discover where the line between effects and animations lies, and so I’ve made a sort of arbitrary decision to include examples of anyone who used any sort of effect in their work that either made the film more than it could be with normal camera work, or that mimicked or perhaps even later inspired animation techniques, such as Cohl’s “The Haunted Hotel”.

Méliès also seems to be the first (probably not the only but certainly the first) film maker I can see who made a satirical religious film, in his “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” (1898) in which a monk worshipping at the foot of the cross is plagued by women who appear out of nowhere and attempt to seduce him, one actually taking the place of Christ on the cross. Surely controversial for the time, and in Catholic France, surely very courageous.

Without question though, his most famous and enduring film is the aforementioned “A Trip to the Moon” (1902) which has been generally accepted as the world’s first science-fiction film. I think everyone recognises the famous shot of the moon, a face looking none too pleased as the rocket carrying the space pioneers lands in its eye.