Invasion!

Invasion!

It’s probably fair to say that nobody in Scotland actually trusted Edward, and that war with England could not have been too far from anyone’s mind, especially when the king, after having chosen the new ruler of his troublesome northern neighbour, started throwing his weight around: demanding cases be heard in England and not Scotland, summoning the king himself, John Bailiol, to court (he refused to go, sending his envoy instead, which must have spoken volumes). But Baliol, though a weak and ineffectual king (and possibly chosen by Edward for that very reason, where the fiery Bruce, who had nearly as strong a claim, might have made a more formidable opponent for him) knew Scotland could not hope to oppose the might of England alone, and so sought help.

Turning to England’s old enemy (no, not Ireland: what use would we have been to the Scots?) Balioli sent emissaries to King Phillipe IV of France, seeking a treaty, which was duly signed as the Treaty of Paris in 1296. Suffice to say, Edward was not amused and sent his armies to attack Scotland, mustering on the borders of Newcastle. They were met by a Scottish army headed by John Comyn (not the same one who had contested the crown, but his cousin) who took and burned Carlisle, but without siege engines had to leg it back across the border. Edward’s armies then crossed into Scotland and took Berwick, and the two armies finally met for battle at Dunbar in April 1296.

It was over in a matter of months. Roundly defeated at the so-called Battle of Dunbar, the Scots retreated and Edward advanced, taking Edinburgh and Stirling Castle (the latter of which had been abandoned), and by July John Bailiol had surrendered. Edward stripped him of his crown and had him and his nobles sent back to London to the Tower, Scotland completely under his heel now. He forced all the nobles and clergy to swear loyalty to him, and to reinforce the point that Scotland’s independence was at an end, took the famous Stone of Scone, which had been the location used for the coronation of the Scottish kings since the ninth century, back to Westminster, along with the other trappings of Scotland’s monarchy, the Black Rood of St. Margaret - said to have been a piece of the cross on which Jesus was crucified - and the Scottish Crown.

Invasion! - the Rematch: Brave Hearts and Broken Bones

Defeated but ready to rise again, Scotland simmered with anger at the treatment meted out to it by the English king, and as the country rose in open revolt against its English occupiers, two famous names were to be written in the annals of Scottish history. One we all know, the other perhaps not so much.

Andrew de Moray (died c. 1297)

Andrew de Moray (died c. 1297)

The Moray dynasty was no stranger to independence; they even resisted joining the Scottish nation until the 12th century, when the Flemish noble, Freskin, to whom Andrew’s family traced their lineage, led an uprising on behalf of the king, David I, and took Moray for him. However resistance continued through the reign of successive kings, and it would not be until Alexander II brought events to a final - and fatal - excuse the pun, head. This was accomplished by having his soldiers take the infant heir to the throne of Moray and smash her head against the market-cross. Proof that Scottish kings could be just as brutal as English ones.

During the first Scottish War of Independence, Andrew rode with his father against Robert Bruce in Carlisle, in the army raised by John Comyn, wreaking havoc across the countryside when they could not get into the castle, killing and burning and pillaging, and all the sort of things you do when you can’t get into a castle and do all your killing there. But when the Scots were quickly defeated by the army of Edward I, Andrew’s father was taken prisoner and died in the Tower of London two years later, while he himself was held at the lower-security Chester Castle.

After defeating the Scots Edward was not exactly magnanimous in victory, imposing heavy taxes on the people, seizing castles and installing English lords to run the place. His plan to force Scottish men - including nobles - to fight in his armies in Flanders did not go down well, and resentment, already simmering, began to boil over. At the beginning of 1207 Andrew Moray escaped from Chester Castle and made his way back to Scotland, just as another rebel raised his flag against the English. You may have heard of him.

William Wallace (c. 1270 - 1305)

William Wallace (c. 1270 - 1305)

If Scotland was polytheistic instead of Christian, it’s pretty certain that WIlliam Wallace would rank high among its pantheon. As it is, he is known as one of Scotland’s greatest and most legendary heroes, and even if the movie Braveheart has taken some liberties with history and the truth, Wallace is certainly remembered as one of the country’s finest and most noble and loyal sons. Described as "a tall man with the body of a giant ... with lengthy flanks ... broad in the hips, with strong arms and legs ... with all his limbs very strong and firm" and though historians differ on various aspects of his story, it is known that his first act of rebellion took place as Andrew Moray was making his escape from English captivity, the murder of the High Sherrif of Lanark, William de Heselrig, after which he joined William the Hardy, Lord of Douglas, to carry out the Raid of Scone, where they put the Justice of Scotland (appointed of course by Edward) William de Ormesby, to flight, and then set up base on Etthick Forest, in a sort of Scottish echo, perhaps, of another famous outlaw.

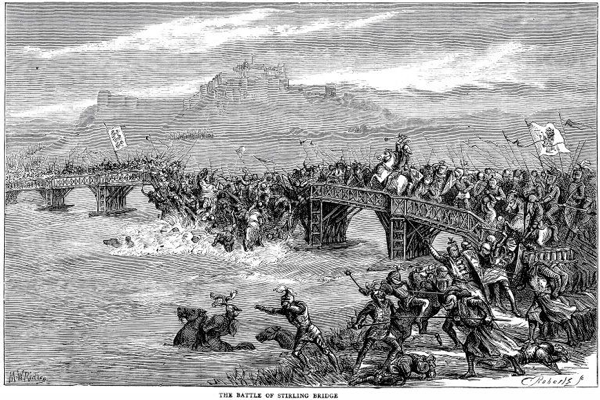

Wallace’s greatest triumph though undoubtedly was the Battle of Stirling Bridge, where he and the forces of Andrew Moray, who had joined up earlier, dealt the English a crippling blow.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge (September 11 1297)

The Battle of Stirling Bridge (September 11 1297)

Playing for time, the Earl of Surrey, who held Stirling Castle for Edward, sent emissaries, including two Dominican friars to negotiate with Wallace and Moray. He was concerned about the long narrow passage from the castle across the river which would put him at a disadvantage, facing a superior number of his enemies, and no doubt hoped for reinforcements. Wallace was unimpressed: "We are not here to make peace but to do battle to defend ourselves and liberate our kingdom. Let them come on and we shall prove this to their very beards."

Can’t get much plainer spoken than that! Opting, for some reason, for a direct attack from across the bridge, rather than trying to outflank the Scots further upriver, as had been suggested to him, the Earl led as many of his men onto the bridge as would fit at once, but the Scots poured down from the hills onto the bridge and slaughtered them, cutting off any chance of reinforcements from the rear. Losing his nerve completely, the Earl ordered the bridge destroyed, and retreated, leaving Wallace and Moray victorious, though Moray had been mortally wounded and would die soon after.

Stirling Bridge nevertheless ranks as a huge achievement for the Scots, the first time their armies had taken on the English and not only won, but routed them utterly, and on their home soil. Wallace went on to lead an large scale invasion of England, through Northumbria and Cumberland, and Edward prepared to reciprocate.

Wallace, however, was no fool, and knew that despite his victories he could not hope to take on the full might of the English army, so his men avoided Edward’s troops, shadowing them and relying on falling morale to send the English back home as food supplies began to run out. Partially, this did work, as Edward had to put down a mutiny by his own men, mostly Welsh adventurers, but then received intelligence that Wallace was camped at Falkirk, waiting to harass his forces (but not expecting a full-on battle) and he rode to meet them. This time, things didn’t go so well for Braveheart.

The Battle of Falkirk (July 22 1298)

The terrain was not on the Scots’ side now, a flanking strategy preferred by Edward’s commanders who picked off the cavalry ranged behind their formations of schilltrons - tightly packed formations of men with spears and pikes - but could not make any further progress against the spear walls. However with their own archers picked off by the English, this left the schilltrons unprotected, with nowhere to run once the English arrows began falling, and as the lines of spearmen began to fall in numbers, opening gaps in the wall, the English cavalry charged in, wreaking havoc. Backed up by the infantry, it wasn’t long before they had slaughtered or routed all the Scots, and the day was Edward’s.

The problem appeared to be twofold: first, the Scottish had not been prepared for or expecting a battle, unlike at Stirling, where they had controlled everything, and second, the main military genius behind that previous victory is believed to have been Moray, who was dead by the time Falkirk was fought. Wallace, though an able commander when performing hit and run, guerilla-style raids, turned out not to be a strategically-minded man, and basically led his forces into a trap against overwhelming odd and with no real plan.

After Falkirk Wallace renounced the Guardianship of Scotland, conferred upon him when he had been made a knight of the realm after Stirling, and is believed to have travelled to France to look for assistance from the other old enemy of the English, with a possibility of also going to Rome, though this is not confirmed. He returned to Scotland in 1304, where he fought against the English for another year before finally being betrayed and delivered to the English king. Tried for high treason, he sneered that “I could never be a traitor to Edward as I was never his subject.” The king was not impressed, and ordered him to be hung, drawn and quartered at Smithfield. In case anyone for some reason doesn’t know that that entails (haven’t you seen Braveheart? They more or less got it spot on) here are all the gory details.

When hanging was too good for them - the awful price of treason

When hanging was too good for them - the awful price of treason

Reserved, so far as I know, for the capital offence of treason alone, hanging, drawing and quartering was perhaps the most gruesome, humiliating and painful death ever devised by man. Well, maybe crucifixion, but still - it gets you out in the fresh air, doesn’t it? Treason was probably the very worst crime a subject of the king or queen could commit, and so it was proportionately punished, both to ensure the miscreant died the worst death possible and to serve as a dire and stark warning to others who might be considering doing the same.

It all began (after, presumably, days of torture, whether for information, confession or just revenge is probably unimportant) with the criminal being dragged - sometimes on a board, sometimes just on a rope or chain - through the streets behind a horse to his or her place of execution. Obviously hardly the least comfortable of ways to travel, the prisoner would already be in pretty poor shape by the time he arrived at the gallows, at which point he would be strung up, hanged, but not in the traditional way. There would be no drop, no quick breaking of the neck, oh no. This was not hanging to kill - not yet - merely to hurt, cause panic, humiliate, terrify. And it was far from the worst of the punishment.

After a few minutes being choked on the end of a rope (as the audience cheered, spat, threw things and cursed at the criminal) he would be laid flat on the platform, his chest bared. A none too gentle incision would be made in his chest, something I guess like they do in a Caesarian section, except rather than draw forth a baby the executioner would draw forth the innards and guts of the man, which would be pulled out and burned before his - supposedly still alive and able to see - eyes, his,um, tackle cut off and burned too, his head then removed and his heart torn from his chest (not sure if that happened before or after the beheading, but given that he was supposed to witness the burning of his other organs, and that removal of the heart causes instant death, I’d say after). Finally, quite dead now, his body could be quartered.

This entailed chopping the body up into four parts, most often centring on the two legs and two arms, these often sent to places in the country where the criminal had been supported, lived, fought or which for some other reason had connection to him. His head would usually be placed on a spike atop London Bridge or the Tower of London, as a clear and visible and enduring (until it eventually fell apart or was picked clean by birds) warning of the terrible price to be paid by those who raised their hand against the monarch.