So why did we get so distracted with the history of Scotland, you ask? You may remember (or you may not; it’s been some time now as I went through this) that I was trying to show how the Scottish had as much reason to hate the English as we do. They too fought for their independence, but were thwarted by their southern neighbours at every turn. They were occupied, oppressed, in some cases almost ethnically cleansed by successive English kings, but I suppose at least they weren’t persecuted along religious lines in the way we were. Nevertheless, it’s clear now, or it should be, why, given a choice between supporting the people who shared the landmass they were on or those of an entirely separate island to the west, Scotland would always consider Ireland to be allies, comrades in arms, fellows in suffering under the English tyrannical boot.

Which brings us back to here.

Skeletons in the Field: Ireland’s Forgotten Famine 1740 - 1741

Skeletons in the Field: Ireland’s Forgotten Famine 1740 - 1741

When we think of famine in Ireland, when we recall the hardships that forced hundreds of thousands of our forebears to abandon our native country and seek sanctuary in America, when we talk of coffin ships and bodies piling up in the streets and the inhumanity of the English landowners, we do something of a disservice to those who died in the previous famine, which took place almost a century the Great Famine, but was, in many ways, worse.

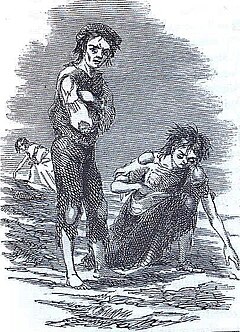

While there had been, as already related, widespread famine across Europe in the earlier centuries, no single country was hit as hard in the eighteenth century than Ireland. This was due to many factors, some of them to do with nature, but more to do with humanity, or rather, the lack of it. The baser parts of humanity - greed, lack of compassion, inequality, brutality, thoughtlessness and prejudice - all helped contribute to one of the biggest humanitarian disasters in Irish history, though sadly not the last. By the time it was finished, it would have wiped out almost twenty percent of the population of Ireland, almost half a million people, making it even more devastating, in ratio, to the Great Famine of 1845-1852.

The principle cause of the famine was the weather, and a reliance by the Irish upon crops that formed the basis of their diet. Grain and potatoes were the staple of Irish families, sometimes (though not by any means always) supplemented by fish or duck, but usually only in coastal areas where such game could be found. After relatively mild winters over the previous decade something called The Great Frost hit Europe. Nobody knows what caused it exactly, though links have been suggested with volcanic activity. Wherever it came from, it froze the land, freezing over rivers like the Shannon, Liffey and Boyne, and even inside it was freezing, indoor temperatures (though few records survive from the time) stated to be -12 Celsius (10 Fahrenheit) while the single outdoor reading spoke of “thirty-two degrees of frost.” All across Europe lakes, waterfalls, rivers froze, fish died and howling winter winds battered the continent.

People tried to keep warm but it wasn’t easy. There were no coal deliveries for months due to both the coal factories in Cumbria and South Wales freezing, and the quays to which they would have been taken also in the grip of the relentless ice, and when deliveries did resume, perhaps not surprisingly, coal prices had skyrocketed. People desperately salvaged any wood they could find to burn, stripping hedges, ornamental trees and nurseries. Not only that, but had there been any wheat it could not have been milled into bread to feed the hungry populace, as the mill wheels had frozen in place.

To be fair to them and give credit where it’s due, the Protestant landowners did not stand idly by, providing coal and meal to the poor, and the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Duke of Devonshire, issued an order prohibiting the export of grain outside of Ireland, other than to England. To be cynical about it, these measures were likely not taken out of the goodness of the gentry’s hearts; they needed these people to work in their factories, mills and fields, and probably feared that too many deaths would impact upon their business, and therefore their pocket. Still, they did a hell of a lot more than their successors would a century later.

Things went from bad to worse as the potato crop failed, all potatoes destroyed by the frost, and this was followed in the spring by a drought, as the expected rain did not make an appearance, and in addition corn and wheat crops failed, leading to the elimination of virtually the entire food supply in Ireland. The harsh drought, coupled with the ferocious winter winds, which continued into the spring, also killed off much cattle, sheep and other animals, and rural dwellers had no recourse but to descend on the cities, begging on the streets and leading, eventually and rather inevitably, to conflict.

The trouble was that, for some reason, the country folk had not considered that their urban counterparts might be just as hungry and helpless as they were. Hungry they were, helpless, not quite. In mid-April a band descended on the docks at Drogheda and damaged a ship loaded with oatmeal which was bound for Scotland. Exports were quickly stopped after that. What didn’t stop was the unrest, anger and indignation at the authorities, with stories going around of food being hoarded, provided to the more well-off. Food riots broke out, first in Dublin and then all over the country. Many people were shot in an attempt to control these outbreaks.

Some respite seemed finally at hand in Autumn, as the cold decreased and cattle began to recover, but they were weak and few gave milk or birth, then in October a huge blizzard hit the country, and the expected rains finally arrived - no longer welcome - leading to large-scale flooding. These were backed up by freezing temperatures which turned the rain to ice and clogged up the rivers, proving a hazard to shipping. With the weather so unpredictable and harsh, those who had food to sell knocked its price way up, or hoarded what they had for fear they might not be able to get any more. Food riots again exploded. The country was on the edge of famine.

From the

Caledonian Mercury, 1740

Dublin, Jan. 11. The Frost still continues here very severe. Numbers are in Want, the Hardness of the Season not permitting them to work ; and Letters from all Parts of the Country give most melancholy Accounts of its Effects, the Mills being stopt they cannot get their Corn grinded, and the Poor whose chief Support is Potatoes are in extreme Want, they being mostly spoiled in the Ground. All the Rivers in and about Cork in Ireland are so frozen up, that People frequently walk 3 Miles upon the Ice. There are Tables and Forms on the Liffey, at Dublin., for selling Liquors . It was also intended to roaft an Ox upon it: And the Thermometer was many Degrees of Cold more than ever known.

Poet William Dunkin put it in more flowery, but no less deadly language in 1742, in his poem

The Frosty Winter of Ireland, in the Year 1739--1740

:

…Beneath the glassy gulph

Fishes benumb’d, and lazy sea-calves freeze

In crystal coalition with the deep.

…The long resounding waves

Of naval ocean, whitening into foam

Boil from the nether bottom, and uprol

Successive, fluid mountains to the stars.

Not sandy shores at other times expos’d

More shatter’d prows, or billow-broken keels:

But if the waves had haply roll’d to land

Some, warm with vital motion, and a-broach

With oozy brine, they stiffen at the breath

Of Boreas, marrow-piercing, and adhere

In senseless union, to the frozy rocks.

Apart from those dying of cold or pure starvation, there were many deaths due to other associated diseases, such as typhus and dysentery, as related in

The Newcastle Courant which reported

…an uncommon Mortality among the poor People by Fevers and Fluxes, owing no doubt in a great Measure to their poor Living, the Price of Corn being risen to an excessive Rate…

The Lord Mayor of Dublin, along with the Chief Justices and the Lord Chancellor, passed legislation to reduce the price of corn, and Archbishop Boulter, one of the aforementioned Chief Justices, used his own money to arrange to feed the poor. Those found to be hoarding private stocks of grain were induced to share it among the hungry poor, and Kathleen Connolly, the widow of the Speaker William Connolly, already having made efforts to feed the poor on her own initiative, provided work for those who had none. Another Chief Justice, Henry Singleton, also put his hand in his pocket to help the needy.

A curate in County Monaghan, Patrick Skelton, described the scene of the famine:

"Whole parishes are almost desolate, and the dead have been eaten in the fields by dogs for want of people to bury them. Whole thousands in a barony have perished, some of hunger and others of disorders occasioned by an unnatural, putrid and unwholesome diet."

The weather finally began to turn near the latter half of 1741, and though the harvest was not exactly great, at least there

was one. Life began slowly to return to some semblance of normality; the dead could be buried, losses counted and arrangements put in place to ensure something like this, an event which was called “The Year of Slaughter”, or in Irish,

bliain an áir, never happened again.

Except, of course, it did.