Éirí Amach! The 1798 Irish Rebellion: Rise up fellow Irishmen!

Éirí Amach! The 1798 Irish Rebellion: Rise up fellow Irishmen!

We’ve seen, mostly through the stories of the lives of the men and women who led or were influential in the coming rebellion, how things came to a head, and with the imposition of martial law on Ireland in March, following the arrest of most of the leadership of the United Irishmen, the rising began. It was of course doomed from the start. Much has been made of the inexperience and even the courage of some of the officers leading regiments, and while Ireland had never had as such any sort of proper army and still suffered from internal divisions within the society - some, like Emmet and McNevin wishing to wait for the faint hope of French help - the British had been putting down rebellions and uprisings for centuries. They were superbly trained for it, had an innate dislike of the Catholic Irish, and spared no effort to brutally suppress what they saw as treason against their monarch.

As in so much of history, Ireland was f

ucked from the beginning.

On the face of it, for an Irish rising the plan was not too bad. It was, as usual, scumbag traitors who ballsed the whole thing up. The original idea was to, unsurprisingly, take Dublin and hold it, with the counties around rising in support and thereby blocking any chance of the capital being relieved from outside. In one way, it made sense: go for the centre of power right away and essentially decapitate the snake. Osama had the same idea, only he nearly succeeded whereas the Irish were betrayed. And the one major flaw with the plan was that if you attack the centre of power and fail to take it, you’re then facing the might of the enemy, on his “home” turf, as it were, like trying to take a castle and finding yourself surrounded by its defenders. Dublin hit back hard at the rebels, sending overwhelming forces to the intended assembly points, arresting the leaders before they even had a chance to lead, and putting the fear of God into the Irish, so that those who could quickly dispersed, even throwing their weapons in the rivers so as not to be arrested.

In essence, the rising was over before it got a chance to start.

Or was it?

Dublin rose as planned, and fighting was fierce, spreading quickly throughout Leinster, with the heaviest fighting (and losses) taking place in Kildare, Meath and Carlow. One of the major turning points of the short-lived rising though was southeast of Dublin, in the county of Wexford. For whatever reason, this smaller county had not been seen as significant by the British, and so they were more than surprised when not only did it rise, but produced the most successful battles of the rebellion, one of which has gone down in Irish folklore.

After the capture and torture of Anthony Perry, a senior United Irishman, other leaders were arrested and executed. With this news, and the intelligence of further atrocities committed in nearby Wicklow, the United Irishmen attacked, their first major engagement something less than a battle, as forty rebels faced twenty militia at the village of The Harrow, killing their commanding officer and putting the rest to flight. The official report:

"On arrival in Ferns, Lieut. Smith and a party was ordered towards Scarawalsh, where the murders were committed, to see if this information was true, and Lieut. Bookey with another Party rode towards the Harrow, where he met a large party of Insurgents armed with Pikes and some Arms. The Lieut. rode before the Party, and ordered the rebels to surrender, and deliver up their Arms, on which they discharged a volley at the Party, accompanied with a shower of stones, some of which brought Lieut. Bookey from his horse, as also John Donovan, a private in the Corps. The party after firing a few shots, finding themselves overpowered by the Rebels, retreated to Ferns, where they remained ‘till day break, melancholy spectators of the devastation committed by the Rebels. The information of the Murders at Scarawalsh found to be true."

The next major engagement was at Oulart Hill, where this time the odds were very firmly again on the side of the Irish, but much more so: about 110 militia faced over 4,000 angry Irishmen. There could only be one outcome. Finding the massive force of their enemy occupying the high ground and, perhaps proving the English had learned little since the days of Andrew Moray and William Wallace, they advanced to meet them and were cut down almost to the last man. News of the great victory spread throughout the county, and soon rebel forces controlled Enniscorthy, Gorey and Wexford Town itself. Finding his troops penned in at Wexford, the commander of the fort at Duncannon, General Fawcett, led 200 men to bolster the garrison there. Heavy artillery was to follow.

Duped into thinking the road ahead was safe, the slower force bringing the big guns was attacked in an ambush at the Three Rocks, in Forth Mountain, and all but wiped out. Their guns were seized, now in the hands of the rebels, and the survivors left to rendezvous with Fawcett, who realised his guns were now likely to be used against him, and headed back to the fort, leaving Wexford’s commander, General Maxwell, to come out hunting for him, and also run into an ambush from which he barely escaped. Finally realising how desperate his situation had become, Maxwell sued for peace while in reality using the sending of the envoys as a chance to have his men slip away quietly, and like true English bastards they took thier revenge on the locals, burning, raping and murdering as they made their way to Duncannon.

However, the rebels had achieved an astonishing victory, much more than those in the capital had managed, and the county of Wexford was almost entirely in rebel hands.

Firmly established now, the Irish set up a French-inspired Committee of Public Safety, and divided their forces, half to head to Dublin and half to New Ross. The latter encountered stiff resistance and were soundly defeated at the Battle of New Ross, despite outnumbering the English about five to one. But they had cannon, and the Irish were mostly just armed with pikes, not to mention that the attack had been anticipated and prepared for, the defences around the city strengthened and ready to withstand any attack. Despite the attempts of the Irish leader, Bagenal Harvey, to negotiate the town’s surrender, his emissary was shot down under a flag of truce, and the enraged Irish charged. Perhaps this was intended, a ruse to make them lose their heads and throw caution to the wind. If so, it worked.

In true Irish fashion, the rebels drove a herd of cattle through the gates, and when the British cavalry charged they were driven back. Fierce and savage street-fighting ensued, in which the rebels took heavy losses but managed to secure most of the town. Unfortunately, their lack of ammunition proved their undoing, and when reinforcements arrived they had nothing to face them with other than pikes. After a pitched battle they were finally driven out of New Ross and the British re-assumed control of it.

And then the massacres began.

I’m of course Irish, so will generally side with my historic countrymen, and lord knows the English had a reputation, well deserved, for brutality and inhuman treatment of prisoners, but it would be unfair and revisionist to ignore the part played by the Irish in the slaughter that followed. I’m not going to attempt to excuse or explain it, as I don’t think there’s every any excuse for what is without question cold-blooded murder (well, hot-blooded, but you know what I mean). I think the belief that one side is always a) right and b) honourable in any war or conflict is a fallacy; we all have it in us to be brutal, or to quote Nick Cave, people ain’t no good. Perhaps to take that further, the wisdom of those merry minstrels, Slipknot, might suffice: people=sh

it. Everyone likes to think they would never do that, never could do that, but for every Nazi prisoner tortured or every American soldier mistreated by the Japanese you can bet there are equal atrocities committed on the other side. Nobody is immune to the madness of war, and good guys do not necessarily wear white, or indeed, black.

Or in this case, green.

In the town of New Ross, days of murder ensued, with both captured and trapped rebels and ordinary citizens - some of whom were Protestant - killed. Many burned alive. In fact it was said that more rebels were killed after the battle than during it. In retaliation, Scullabogue happened.

A small farm and outbuilding outside of the town, Scullabogue had been used by the rebels as a staging post, and all those believed to be enemies or potential spies rounded up and locked in a barn there. These included women, and indeed children. When news of the defeat at New Ross was brought by those escaping the battle, passions were inflamed, and thoughts of revenge bubbled over into violence. Although the guards drove the rebels back twice (Irishmen fighting Irishmen, how odd

) they eventually bowed to pressure and allowed some of the prisoners to be shot, however that wasn’t enough and the barn was torched, those trying to flee shot, stabbed, beaten to death or forced back into the flames. All but two of the prisoners perished. The event horrified General Thomas Cloney, who reported “The wretches who burned Scullabogue Barn did not at least profane the sacred name of justice by alleging that they were offering her a propitiatory sacrifice. The highly criminal and atrocious immolation of the victims at Scullabogue was, by no means, premeditated by the guard left in charge of the prisoners; it was excited and promoted by the cowardly ruffians who ran away from the Ross battle, and conveyed the intelligence (which was too true) that several wounded men had been burned in a house in Ross by the military.”

With New Ross now again in English hands, General John Moore marched to meet the rebels who had escaped, with a force of about 1,500 men, intending to join up with the maniacal Lake and his contingent and trap the Irish in a pincer movement. Lake was delayed though and so Moore took on the rebel force at Foulkesmill by himself. Though facing nearly four times his own number, and though the Irish had the high ground, Moore rallied his men as they attempted to break in panic, and, reformed and resolute, they charged the Irish positions, raining cannon fire down on them and driving them off. This action served to reopen the road to Wexford, which had been in rebel hands since the city had fallen.

Spectacularly bad luck and poor planning attended the Battle of Bunclody, where rebels forced their way with captured artillery into the small garrison town, forcing the retreat of the British, leaving some few Yeos trapped there. As the Irish celebrated, the garrison turned back around and launched a surprise attack against the town, which the rebels had failed to fortify (probably too drunk) and thus they were driven out and the battle lost.

The Battle of Arklow followed, as the Irish tried to spread the rebellion beyond Wexford, but were repulsed by Francis Needham, 1st Earl of Kilmorey, though they did manage to destroy one of the British cannon with captured guns. Their exultation was short-lived though, as Needham’s artillery replied forcefully, and the rebels fell back. Attempts to pursue and kill them largely failed though, and by the time they melted away into the night they were unaware that Needham’s garrison were almost out of ammunition, as were they.

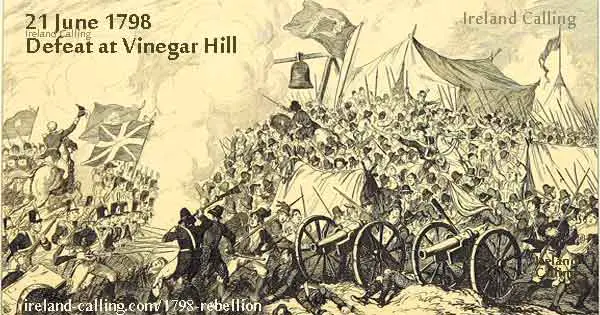

The end was looming for the rebels, but before they were defeated they again took loyalist prisoners, this time bringing them to Wexford Bridge where they were piked to death, and their bodies thrown into the river. A massive force of nearly 18,000 British soldiers poured into Wexford under the command of the dreaded General Lake, and the United Irishmen gathered to meet them and make their last stand at Vinegar Hill. It was indeed to leave a sour taste in Irish mouths, as it was the turning point, and the end, of the rebellion in Wexford.

With few firearms and most only bearing pikes, and with women and children sheltering with them, the Irishmen had no chance against the well-drilled, efficient and deadly British Army, furnished with all the latest weapons and the know-how to use them, as well as artillery which could bombard the Irish from a distance. Each time they were hit the Irish would retreat into an ever-tightening circle as the British moved their artillery closer and continued to shell them. Things were desperate. Meanwhile, in Enniscorthy, just down the road, the defenders were doing much better, pushing back General Johnson’s light infantry division and holding the town. However when Johnson brought in heavy cavalry they could not stand, and were eventually driven out, though they managed to hold the strategically important Slaney Bridge.

As the rebels on Vinegar Hill were routed, more atrocities ensued, wounded being burned to death, women raped, the usual horror brought about by the victors in any battle if they’re fired up enough and there’s sufficient hatred for the enemy. Driven out of Wexford, the survivors spread beyond the county to carry on what remained of the rising in guerilla raids.