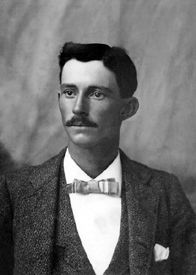

John M. Larn (1849 - ?)

John M. Larn (1849 - ?)

A salutary tale showing why a good vigilante does not make a good sheriff, Larn was elected to the post in Fort Griffin, Texas, in 1876, and immediately set about abusing the trust of the people of the town in him. Looking back over his career to that date, it’s obvious why he was never going to be a good upholder of the law, as he was mostly on the wrong side of it prior to this. When his boss, a rancher in Colorado, accused him of stealing one of his horses in 1869 he shot the man and fled to New Mexico, where, believing the man was after him, he shot and killed a sheriff. While working for another rancher, Bill Hays, on a cattle drive back to his old stomping grounds in Colorado in 1871, he shot and killed three more men, two of them Mexicans.

By now he was established in Fort Griffin and considered a pillar of the community, having married one of the local powerful family’s daughters, and then he got involved with the vigilante group The Tin Hat Brigade (sounds like someone who believes the CIA are monitoring our communications and aliens are trying to infiltrate our brains, doesn’t it?) and turned on his old boss, leading a posse against Hays on a charge of cattle rustling (true or not, I don’t know) instead of bringing them in, killed every last one of them. Notwithstanding this - or who knows, maybe due to it - he was made sheriff three years later, and entered into a contract with the local garrison to supply them with cattle.

However he decided the least expensive way to fulfill this contract was to take cattle from the herds of other ranchers, and so became a cattle rustler, something of which he had been privately suspected prior even to pinning on the tin star. He would not wear it long though, and whether due to pressure from the town or in order to concentrate fully on cattle rustling, he resigned the next year and with his ex-deputy went fulltime into the business of raiding herds. He continued to supply the fort, and stepped up his tactics of intimidation, waylaying ranchers and cattle men, shooting at their houses and shooting their horses, and generally prosecuting a reign of terror across the territory. Showing how little the authorities knew or cared about his extracurricular activities, he and Selman were made hide inspectors of Shackelford County, which gave them easy access to cattle - foxes in charge of the henhouse, indeed.

His crimes eventually came to light and he was arrested, though later released, but when he shot and wounded a rancher a warrant was issued for his arrest. Shackled to the floor of the cell to deter any attempts by his supporters to free him, it was in fact his old friends the Tin Hats who stormed the jail, not to set him at liberty but to hang him. As the chains made that impossible, they opted for shooting him instead.

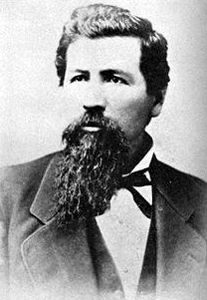

Edward “Ned” Bushyhead (1832 - 1907 )

Edward “Ned” Bushyhead (1832 - 1907 )

A Cherokee miner, Ned was seven years old when his family joined the infamous “Trail of Tears” as the Native Americans were forcibly resettled as the West began to open up to the white man. They ended up in Oklahoma, where Ned took a job as apprentice on the local newspaper,

The Cherokee Messenger, later moving to Arkansas where he worked as a printer. In 1850 he and his brother heard the call of gold and headed to California, but three years later Ned was running his own newspaper in San Diego. He became a fixture there, well respected, and after selling his interest in the paper he became deputy sheriff in 1875 and sheriff in 1882, a post he would hold for two terms.

In 1899, on the very cusp of the new century, he became Chief of Police, and remained in that post until four years before his death in 1907. He was described as intrepid, brave, courteous, patient and sagacious, all qualities very much required in any good lawman.

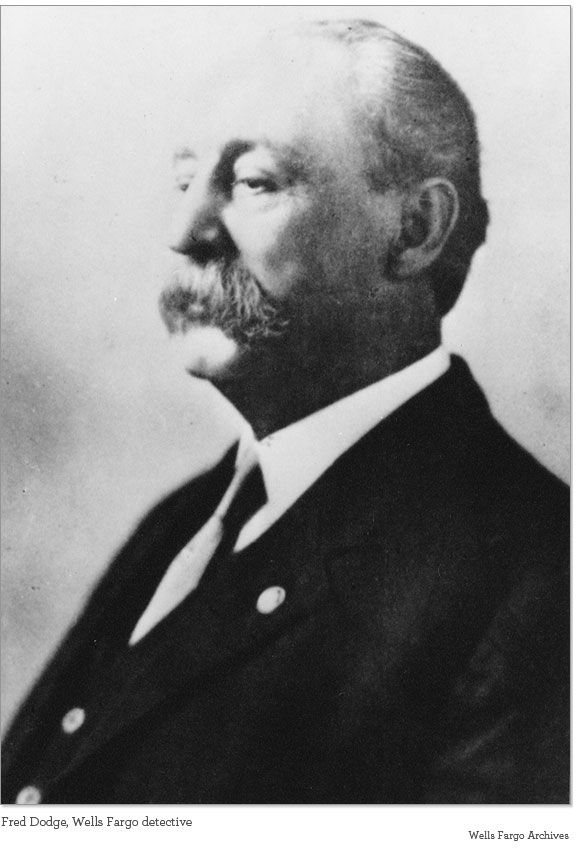

Fred Dodge (1854 - 1938)

Fred Dodge (1854 - 1938)

A man with an appropriate name for an undercover detective, Dodge worked for the Wells Fargo Company in such places as California, Arizona and Nevada. It was in fact while working in Tombstone that he recommended the services be sought of Wyatt Earp to guard the stage line. He became friends with Earp and stood with him and his brothers against the Clantons and was later himself elected constable of Tombstone, while still working undercover for Wells Fargo. He helped US Deputy Marshal Heck Thomas track down the famous Doolin-Dalton Gang. In 1906 he moved with his family to Texas, where he bought a ranch and to which he retired.

George Maledon (1830 - 1911)

Perhaps not strictly a lawman, it can’t be denied though that the end of many a convicted criminal ended with the hangman, and Maledon, with a name like some sort of devil out of Goethe or something, was acknowledged as one of the best. As in the case of every practitioner of the deadly art, no real blame can be attached to Maledon, as he merely carried out the lawful orders of his master, Judge Isaac Parker, the so-called Hanging Judge of Arkansas, whose motto was “permit no innocent man to be punished, but let no guilty man escape” and “Do equal and exact justice”. Of German descent, Maledon came to America with his family when still a child, and they settled in Detroit, Michigan. He moved to Arkansas as a young man, enlisting in the military when the Civil War broke out, having previously been a police officer there.

He cut far from the imposing figure you might associate with a hangman: short, with a little beard, dressed in black and very quietly spoken, not really the kind of person you would tremble before (for his own sake) on your way to the gallows. But soon after the war ended and he returned to Fort Smith, he was appointed as “deputy with special charge of the execution of condemned prisoners”, in other words, the prison hangman. What surprises me is that, unlike later English hangman such as Albert Pierrepoint and John Ellis, Maledon does not seem to have received any sort of basic training, needed no qualifications and was in no way any different to other turnkeys in the prison, so why he was chosen as the hangman is a mystery to me, particularly given his diminutive stature (five feet five inches). Maybe nobody else wanted the post, and because he was said to be a mild-mannered and quiet man, the authorities didn’t expect any resistance from him?

At any rate, he soon became known as “the Prince of Hangmen” and this being a time when hangings were a public spectacle, his fame spread as more and more people attended the hangings at which he officiated. At one point, in September of 1875, he hanged six men at once, before a crowd of almost five thousand fascinated onlookers. The men had of course been condemned by Judge Parker, this event earning him his epithet, and bringing his court the unofficial title of “Court of the Damned”. I’m sure they didn’t, but someone could apparently just as easily have hung a sign over the door to the court reading “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.” There certainly seemed to be no hope for anyone who went into Parker’s court, as any man found guilty ended up dancing his last dance in air.

Though Maledon was famous, he was really more infamous, and people shunned him, as they would mostly with hangmen down the centuries, association with them being seen as an omen of bad luck, the stink of death believed to cling to them, and perhaps some of the blame for the deaths of the criminals too, as it had been he who had launched them into the afterlife, even if the decision was most decidedly not his and he was merely a tool of the justice system. If he had not done it, someone else would have.

In 1878, though hanging was very much still legal, and would remain so well into the next century, it became more a private affair, by invitation only, and a large fence was constructed around the gallows. Spectators were now limited to about fifty, usually the relatives and friends of those the criminal had killed, maybe his own family, officers of the court, dignitaries from the state and so on. Though dedicated to his art, Maledon did evince human feeling when he refused to execute his friend, US Deputy Marshal Sheppard Busby, who was accused and found guilty of shooting another marshal whom he had tried to arrest. Quite why this should be seen as a hanging offence, when it seems clear Busby was only carrying out his duty, I don’t know, but he was sentenced to swing (maybe just unlucky that the Hanging Judge was in town) and Maledon would not drop him. It’s not as if it saved the marshal’s life: Maledon was just replaced for the hanging by another man.

After giving twenty years of his life to the prosecution of state killing, Maledon retired in 1894, but he was not to have a quiet retirement. His daughter, having fallen in with a thief and cheat who turned out to be already married, was shot by the man, Frank Carver, and killed. Though Judge Parker passed the sentence of death upon him, by now the appeal process was in force and Carver’s lawyer successfully argued the death penalty down to life imprisonment. As a man who had meted out final justice to what he surely believed to be deserving men, the overturning of the judge’s verdict sickened Maledon, who believed the system was going soft on criminals. He took to the road with a sort of carnival of the dead, displaying his hangman paraphernalia, telling stories of those he had hanged and showing their pictures.

If, for most of his life, Maledon was a quiet, reserved and mostly unremarkable man, he died as he had lived really. He became seriously ill as he entered his mid-seventies and moved into an old soldiers’ home in 1905, where he died six years later, in 1911.

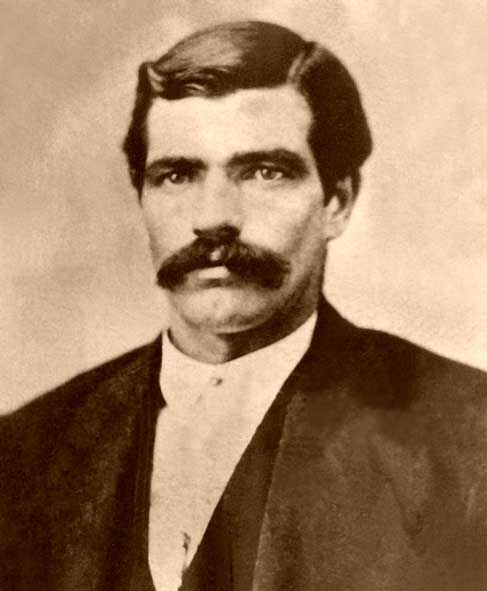

Thomas “Bear River” Smith (1840 - 1870)

Thomas “Bear River” Smith (1840 - 1870)

Whereas I remarked earlier that the idea of a man chosen to be sheriff casting his badge down in the dust, for it to be left there until some stranger riding into town picked it up seemed to me to be nothing but Hollywood hokum, it appears I don’t know sh

it, which will come as no surprise to most of you. How come I don’t know s

hit? Well, because it happened, that's why, at least once, in the rough and dangerous Texas “cowtown” of Abilene. What was a cowtown? One of the stops along the way for the great cattle drives that took place every summer as ranchers drove or paid for their herds to be driven up north to be sold in the cattle markets. Small towns, dependent on the passing trade from cowboys (literally, the guys who herded the steers and bulls were called cowboys, and that’s where the name came from) and their trail bosses, hosted these cattle parties as the drovers passed through on their way north, availing themselves of gambling dens, brothels, saloons and dance halls. Things could, and did, get mighty rowdy when the boys were back in town, and it would be a brave or foolhardy man who would stand up to them and try to instigate, never you mind keep law and order there.

Such a man was Thomas “Bear River” Smith, one of the few who would take the job (another famous marshal having looked into it and said no thanks, heading out on the next train anywhere) and he would pay for it with his life. A professional boxer in his youth, Smith had served in the police force in New York but had to retire when he accidentally shot a fourteen-year-old boy, and took up a post with the Union Pacific Railroad in 1868, which took him to Bear River, Wyoming (presumably from which his nickname sprang). He soon became city marshal, and had to deal with vigilantes who had hanged a member of the railroad who had killed a man. A tense confrontation ensued and the army was called in.

Smith left Wyoming and made his way down south, ending up in Abilene. He took the job as the town’s marshal, and quickly made his name known as “No gun marshal”: having banned all weapons from the town, he utilised his boxing skills to subdue lawbreakers with his fists, but his edict of banning guns was unpopular in the rowdy town, where cowboys liked to ride around shooting off their pistols, settling disputes with hot lead, and generally raising hell. He survived two attempts on his life, but when he went to arrest a local man for having killed a farmer, he was ambushed and shot. His cowardly deputy fled, instead of standing to help him fight off two men. Unfazed, Smith returned fire, but the lawbreaker’s partner grabbed an axe and buried it in Smith’s head. He had lasted less than a year in the job, and would be succeeded by a real legend of the West, Wild Bill Hickok.

No less a personality than President Eisenhower himself later paid Smith homage, saying

“According to the legends of my hometown, he was anything but dull. While he almost never carried a pistol he…subdued the lawless by the force of his personality and his tremendous capability as an athlete. One blow of his fist was apparently enough to knock out the ordinary ‘tough’ cowboy. He was murdered by treachery.”