The Easter Rising, 1916

The Easter Rising, 1916

The last straw: eight hundred years of foreign occupation

The Tudors, the Normans, Cromwell: all had invaded Ireland in its past and subjugated its people, with varying degrees of success down the centuries, but Ireland had been a fiercely independent nation, an island in the most literal sense, with its own language and beliefs and its own ruling classes, and an almost fanatical determination to resist conquest. Of course, this resistance was complicated and diluted down through history due to the everpresent rivalry of opposing factions, so that when the Irish were not fighting the English or some other invader they were invariably fighting among themselves. It's no way to establish a stable government.

In 1169 a loosely-affiiliated band of Norman knights landed in Ireland, with the blessing of the pope of the time, who wished the then-pagan island civilised and, more importantly, to levy taxes on Ireland. He then granted permission to King Henry II of England to assert his dominion over Ireland. In typical Irish fashion, this invasion was sponsored by an exiled Irish prince, Diarmuid of Leinster, who could only see as far as regaining his own throne, and was prepared to sell his country out to the invaders as the price of that restoration of power. This would happen a lot throughout Irish history, not just with the English but with the French, Scottish, Spanish ... anyone a disgruntled or out of favour Irish lord could use as a means of regaining his power. We whine and bitch about "the English invaders", but it's sobering to think that we actually invited them here in the first place!

However, as soon as Henry was recalled to England to deal with pressing matters of state, factions arose within both the Irish and Norman camps, and rival groups, knights and kingdoms faced off against each other. Ireland was again at war. In 1495, as a backlash against rising powers within Ireland --- Norman knights who had "gone native" or indeed former kings or high kings of Ireland before the invasion --- the king imposed English statute law on Ireland. This took power from the previously more or less autonomous Irish Parliament, and in 1543 made Ireland a kingdom, thus coming under the direct control of the English monarch. The secession of Henry VIII from the Catholic Church following his difficulties with the pope regarding his wives, meant that English law required Ireland, as a kingdom of England, to practice the protestant religion, with catholicism, the then dominant belief in Ireland, outlawed and its adherents punished. Henry had monasteries and abbeys confiscated, monks priests and abbots slain, and generally sowed the seeds of discontent among his new subjects.

When his successor, Elizabeth I, was declared by the pope to be a heretic and excommunicated, this set the Irish on an even more direct collision course with their English masters. Devoutly catholic since Norman times, the vast majority of the Irish did not want or intend to change religions, and most had remained catholic in secret during Henry's reign. Elizabeth had taken a different tack, allowing people to keep their religion and refusing to impose Protestantism on Ireland. To the catholic Irish then, this proclamation against the person they saw as their main oppressor and overlord, by the head of their faith, God's spokesman on Earth, hardened their resolve and vindicated in their hearts their right, even duty to rebel and overthrow the English. With the enacting of Plantation policy, whereby English settlers were moved to Ireland to colonise and Anglicise it, Irish lords lost their lands and the native population began to feel like they were being squeezed out by the new invaders. This then led to the Irish Rebellion of 1641, under which the country regained its own government, after a fashion, and catholicism thrived until the arrival of Oliver Cromwell in 1649.

"The most hated man in Irish history"

Although revered and feted in England as a reformer and a leader, Cromwell's name is forever spat with disgust and contempt here. His invasion of the country was a brutal affair, and the stories told of the atrocities his armies carried out, while perhaps coloured and embellished a little, seem to be mostly accepted by historians. Cromwell seemed to view the Irish as savages, hardly human at all and nothing more than an impediment to his assuming total control over both Ireland and England in the wake of the English Civil War. Cromwell, a fanatical Puritan, hated the catholic Irish and saw them all as being heretics. He was also incensed by previous massacres carried out by the Irish in the 1641 Rebellion, and determined to make the blasphemers pay for this slaughter.

Cromwell landed in Dublin and quickly overpowered the attackers who had come to prevent him taking Dublin Castle, where the Parliamentarian centre of power was located. With the capital city secured, and with it a port at which to land his army, Cromwell marched on Drogheda where, after defeating the garrison there, he slaughtered everyone, despite surrender being offered. While one of his lieutenants marched to the north to retake Ulster, Cromwell moved on to Wexford and began negotiating terms of surrender, but in the midst of this his troops broke down the city gates and massacred the inhabitants, burning much of the town. Although he did not order the attack, it is pointed out by historians that he didn't reprimand his men for the act afterwards --- was it some sort of medieval "black op", allowing him what we now call plausible deniability? Whatever the truth, the action became a two-edged sword: some towns, fearing the brutality of his New Model Army, surrendered to Cromwell without a fight, whereas for others their resolve was only hardened, seeing that even if they surrendered they were likely to be butchered anyway.

By contrast, Cromwell's treatment of the surrenders of Kilkenny and Carlow was quite the reverse of that of Wexford and Drogheda; he accepted their surrender terms and honoured them, and no massacre took place. This however may have been in recognition that his excessive use of force and lack of mercy previously was having the opposite effect on his enemies. The re-conquest of Ireland took over two years, and in 1652 the resistance of the Irish was finally and decisively broken when Galway was taken. Following this defeat, the rebel Irish waged a campaign of guerilla warfare against the invader, though eventually even this token resistance melted away as the Irish were allowed to depart the country to serve overseas in other wars, as long as they did not take up arms against England or her allies.

During the colonisation of Ireland by Cromwell, Irish catholics were executed en masse, had their lands confiscated or were deported to the West Indies to work as indentured labourers, essentially slaves. His scorched earth policy produced a massive famine in Ireland, and his hatred of and massacres of catholics fuelled the fires of anti-Protestantism in Ireland which continue even to this day.

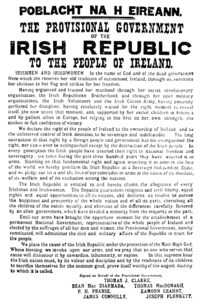

The Rising

In 1800 the Act of Union finally brought Ireland under the rule of the English sovereign, and the powerbase of the English goverment in Ireland was established in Dublin Castle. Ireland though never accepted English rule, and resisted it through various methods, such as the Home Rule bill (defeated twice), the Land League and the Repeal Association, as well as an outright uprising in 1848, but as World War One took the attention of the British away from Ireland, rebel factions there decided the time was right for another rebellion, one that would this time be successful and bring Ireland her own parliament and self-determination. The outrage at the fact that Irish men would be forcibly conscripted into a war that had nothing to do with them just added fuel to an already raging fire. The leaders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) therefore devised a plan which called for two of their number to visit Germany and secure the help of the German army and navy, who would stage a landing on Ireland's west coast. A rising would be planned and executed in Dublin to divert the attention of the British army from the German presence and to pull forces away from responding to it.

The plan however failed, as Sir Roger Casement, an English consul, returning to Ireland on a German U-Boat was arrested and the ship carrying the vital arms shipment was intercepted by the Royal Navy. The date for the Rising though was set and it went ahead as planned on the morning of Easter Monday, April 24. With four key strategic locations being identified for capture, it is the GPO (General Post Office) in O'Connell Street which has gone down in Irish history as the iconic location of the rebels' last stand, and indeed it was their headquarters, though they did abandon it under heavy shelling from the British. Also taken were Jacobs Biscuit Factory, the Four Courts and Liberty Hall, though there were other areas too, such as Saint Stephen's Green public park and Bolands Mill.

Leading the rebels were James Connolly, Padraig Pearse, Eamonn Ceant, Tom Clarke, Sean MacDermott and James Plunkett, the last of whom had travelled with Roger Casement to Germany the previous year. The rebellion was poorly planned: a chance to take Dublin Castle was spurned, as was the opportunity to secure Trinity College, despite both being somewhat lightly guarded. Irish people in the main had not been aware of the Rising and so were taken by surprise and, it is said, treated roughly at some locations including Jacobs and Bolands when they tried to prevent the rebels taking these strategic locations. The fatal undoing of the rebels was their failure to lock down either of the two train stations in Dublin nor the two seaports, which if taken would have denied the British access for the reinforcements they sent as the Rising moved into its second day. By the end of the week, slightly over 1,000 men had increased to nearly 16,000, against a total Irish force of less than two thousand. In many of the areas --- GPO, Jacob's, Boland's, Stephen's Green --- there was little actual combat, as all the British had to do was shell the strongholds or deploy snipers.

"Doomed to failure"

The Easter Rising was over within a week. With heavy casualties on both sides, the Irish rebels were nevertheless easily outgunned and outmanned, and there seems to have been something of a fractured strategy on the part of the rebels. Also, the eternal schisms and arguments between different factions within the IRB led to a weakening of the force that was supposed to rise up, leaving less than two thousand to face the might of the British Army. If indeed they had been intended to, the people did not rise with the rebels; in fact many resented the way they were treated --- some beaten, some shot --- and were unlikely to support them. The GPO, headquarters of the rebellion, was abandoned when the shells landing there set fire to the place, and from their secondary base in Moore Street the rebels could see no way out, and so sued for surrender. On Saturday April 29 Padraig Pearse issued the order to surrender, and the Easter Rising was over.

The reasons for its failure are many, among them the capture of the shipment of German arms being brought to Kerry by Roger Casement, divisions within the leadership, divergent ideas as to what the Rising was about and what its aims were, and what should be done afterwards, and what appears on the surface to have been staggering naivete on the part of the leaders, or commandants of the IRB. Had they secured the train stations and ports then no channel would have existed for the British to ferry in their reinforcements, and the rebellion might have had a much better chance of succeeding. The famous GPO stand appears to have amounted to the leaders holing up in the place and awaiting their fate, as no major offensive was carried out by them, though it's assumed they tried to direct the rest of the Rising from there; mind you, how they communicated I don't know. Also the failure to take Dublin Castle, a fat and waiting target and surely if nothing else a hugely symbolic victory had they achieved it, seems to have been passed up despite the possibility of securing it.

In the end, it would appear that the Easter Rising was badly planned, by men who did not agree on much and that power struggles within the leadership of the IRB led to opportunities slipping by and plans not being properly executed. It's possible that, had all the elements been in place, 1916 would still not have succeeded, but it certainly would have had a better chance than it did.

Aftermath: Legacy and Irish independence

The leaders of the rebellion were all executed by the British. Most if not all of them are now commemorated in street names, many close to where they fought. James Connolly, who had been wounded in the ankle in the battle, had to sit in a chair to be shot. Sir Roger Casement, as the only actual British subject, was tried for high treason and hanged. However, although the Easter Rising was a failure in the immediate sense, the reverberations and repercussions from it continued long on into the next decade. In 1918 the rise of Sinn Fein was almost directly a result of the nationalist feelings awoken by the Rising and more particularly the execution of its leaders. Sinn Fein won 73 seats in the House of Commons but refused to take them in protest, assembling instead in Dublin where in 1919 they formed Dail Eireann, the Irish Parliament which is still today the seat of power in Irish politics, and declaring the creation of the Irish Republic. Thus began the Irish War of Independence, which ended 1921 with a truce and the establishment of the Irish Free State.

Ulster, overwhelmingly Protestant and therefore loyalists to the Crown, sued to be allowed secede from the new State and remain part of the United Kingdom, a boon the King and Parliament in London was only too pleased to grant. This essentially weakened the new Irish Free State, and has ever since remained a bone of bitter contention over the partition of Ireland, as the minority of catholics in what became Northern Ireland felt that they had had no say in the decision, or had been effectively shouted down and shut up. This led to the thirty-year period of sectarian violence and upheaval we refer to as "The Troubles", but that is a story for another day.

What is clear is that without the Easter Rising in 1916, though independence probably would at some point have come for Ireland, it would not have been so soon, and the hand of the British would not have been forced as it was. After the rising, as the smoke cleared so to speak, people began thinking about how they had been treated under British rule, particularly in recent times, and nationalist fervour climbed to a peak, resulting in first the formation and then the victory of Sinn Fein in the General Election of 1918, which itself led by a somewhat circuitous route to the holy grail of Irish independence. Ireland owes, and always will owe, a massive debt to the men who gave their lives for the cause of freedom and independence, and even now, almost a century later, their names are revered in story and song, and their places of honour in Irish history is assured, and unassailable. It's the sort of legacy that led people here recently to ask, in the wake of our ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon which effectively told us to bend over and take whatever Brussels gives us, taking completely away our right to govern ourselves and handing power over to the faceless bureaucrats in Europe, "is this what the lads fought for in 1916?"

A very good question.