Thaddeus Cahill (1867-1934) was a lawyer and inventor who believed that Gray’s Musical Telegraph had far more potential and began to experiment with electronic keyboards on a grand scale.

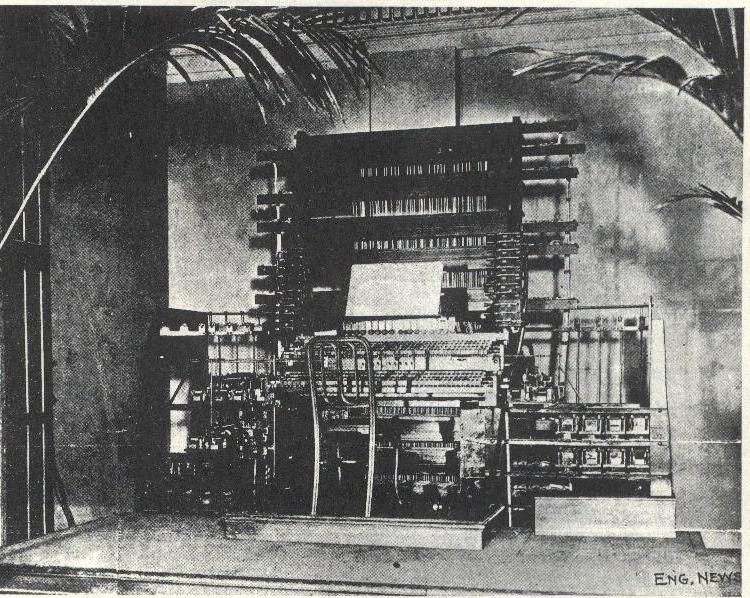

The simple oscillators invented by Gray were too primitive for Cahill’s vision—they had insufficient power. He replaced them with tone wheels. Cahill’s tone wheels consisted of an AC synchronous motor that drove a gearbox that, in turn, drove a series of rotating discs. Each disc had a set of “bumps” on it and the number of bumps and the speed of the disc’s rotation determined its frequency and therefore its musical note. The note was picked up by a magnet wrapped in a copper coil (appropriately known as a “pickup” and the same as today’s pickups). Cahill not only had tone wheels for the principle notes, he added more to play harmonics. The tone wheels generated simple sine waves which sound rather flat. By adding harmonics to a sine wave, we can create any sound in existence.

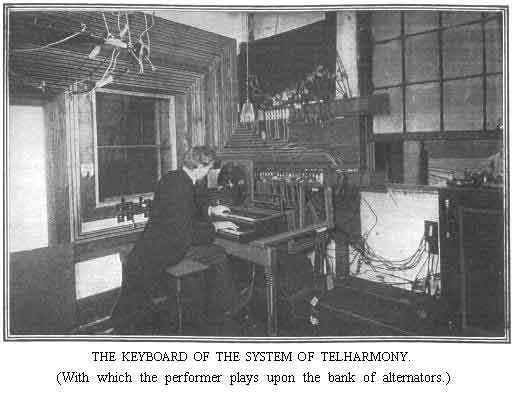

So Cahill’s harmonic tone wheels enabled different harmonics to be activated which altered the timbre of the instrument and enabled it to mimic such instruments as flute, cello, trumpet, bassoon and so on. Cahill patented a keyboard that ran on this principle in 1896 and called it the Teleharmonium (a.k.a. a Dynamophone). Like Gray’s Musical Telegraph, the Teleharmonium’s sounds were made to be broadcast over the phone lines. The phone speakers were attached to large paper cones that enabled everyone in the room to hear the music—another primitive loudspeaker as electronic amplification was not yet known. The Teleharmonium had stops like a pipe organ that enabled instantaneous timbre modulation and there were several keyboard consoles to enable polyphony and foot pedals that added startling effects according to those who have heard the instrument.

Edwin Hall Pierce playing the Mark II Teleharmonium.

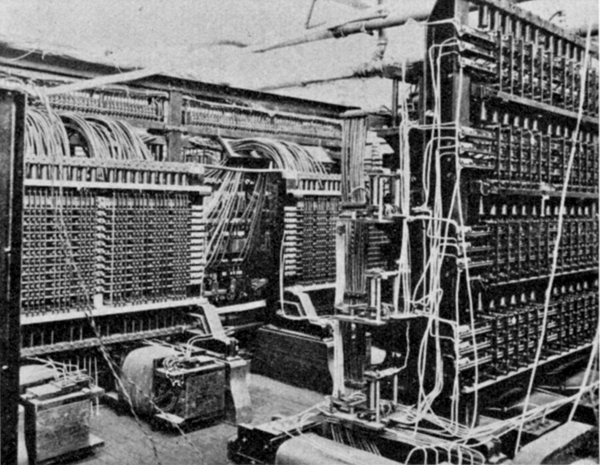

The problem with the Teleharmonium, as versatile and unusual as it was, was the sheer size and weight of it. Cahill’s first model, the Mark I, weighed seven tons. And if that sounds like a lot, the Mark II, weighed 200 tons! The Mark III also weighed about 200 tons. The Mark II cost an incredible $200,000 to build! Obviously, not many Teleharmoniums could be built at that price.

In fact, only one of each model was built. The instrument had its own hall in New York, Teleharmonic Hall, where the entire basement was filled with the electronics that were required (this was before vacuum tubes). Its power consumption was enormous. But Cahill and his backers were hoping to transmit live music to 10,000 or more remote locations via telephone lines. But there was also a problem with cross-talk when broadcasting music over phone lines. People found their conversations suddenly cut off by strange electrical music and people listening to the Teleharmonium transmitting to them from 30 or more miles away would hear snatches of phone conversation cutting in on their musical enjoyment. The Teleharmonium was more advanced than the medium chosen to broadcast it. The cart was hitched before the horse.

The Teleharmonium was like an iceberg—the visible part of it big enough and yet most of it was hidden below, mind-boggling in its enormity.

Thaddeus Cahill

Holes were cut in the floor to accommodate the huge number of wires and cables passing from the consoles to the electronics housed in the basement. There are no recordings of the Teleharmonium and none of the three models built have survived the ravages of time. Cahill’s company went belly up in 1912 when problems with phone line transmission proved insurmountable. Cahill’s brother owned the Mark I after Cahill’s death in 1934, the last surviving Teleharmonium, but it was destroyed in 1962.

Cahill’s indelible contribution to musical synthesis was the tone wheel, which was then used by the Hammond company for their electric organs and is responsible for their trademark sound. By adding extra tone wheels to modify timbre, Cahill also came up with the process of additive synthesis (which we will explain later), also picked up by Hammond. An unexpected side effect resulted when Hammond’s tone wheels were so tightly packed that they sometimes picked up frequencies from adjacent tone wheels, a bleed-through resulting in a harsh, overdriven sound. Initially viewed as an undesirable characteristic, rock and blues keyboardists loved the effect and used it quite often making it rather famous. Today, many electronic organs and digital synths actually have presets for this effect.

Cahill’s invention was doomed no matter what. Once electrical amplification came about in the 1920s, courtesy of Western Electric, the Teleharmonium was truly obsolete. The huge generators and switchboards produced sometimes as much as 14,000 watts of power simply because there was no electrical amplification. Pushing that wattage through phone lines and a small telephone speaker and concentrated with a horn or cone was enough to fill a room with sound but the power usage was untenable. With electrical amplification, 100 watts fills a room easily. With loud concerts in an auditorium, 200 watts generally does the trick. At a large stadium, 500 watts is enough although some bands push it up to 1000 but this generally causes ringing ears in the morning. But 14,000 watts would blow out eardrums and drive sound waves through bodies so hard it would cause internal damage.

Cahill’s backer, Oscar T. Crosby, had hoped that the Teleharmonium could be used to replace the expensive orchestras that played at all the ritziest restaurants and hotels in New York. He could simply hire two musicians to broadcast live electrical music into the dining rooms and dancehalls throughout the city. Certainly an endeavor worthy of funding and experimentation, ahead of its time but that was the problem—the times weren’t ready yet and so the Teleharmonium fell by the wayside.

Interesting photo of a Teleharmonium demonstration. Note the huge horn speaker fed from a telephone receiver. Tremendous power was being generated but with no electrical amplification, the output was merely adequate. Although it looks easy to play here like any other organ, the Teleharmonium usually required two skilled musicians playing on a stack of keyboard consoles and modifying the parameters at the same time. The Teleharmonium was, in fact, a very awkward instrument to play and, in spite of its power, didn’t handle loud music well at all. People thought it too harsh. It turned into a glorified church organ—hardly suitable for dancehalls or ballrooms. Society orchestras were still safe from the unemployment line—for now.

A Teleharmonium documentary:

Magic Music From The Telharmonium Documentary - YouTube