Picking this back up again two years later, what better way to continue than to go, um, backwards? See, it seems to me that I got a little caught up in what we’ll call the start of the Disney era, and thereafter based all my research on animation outside of the USA on that period. But hell, you can go a long way back outside the borders of the United States to find people in Europe who were working on animation - at least, of a kind; crude, obviously, but still important - and who really should be looked into.

So I want to continue the “UnAmerican Animation” feature but take a look back to before the 1930s. Well before, in fact, and run through what countries in the UK and Europe (and even, I see, Ireland!) were doing in the opening decades of the twentieth century. Nothing groundbreaking, I guess, but it seems there was a fair deal of animation development and experimentation going on even then.

UnAmerican Animation: Rockin' Outside the USA (Part III)

UnAmerican Animation: Rockin' Outside the USA (Part III)

Well, obviously you’re going to get a few people claiming to be the father of animation, including Uncle Walt and his rival Max Fleishcher, though in reality people like Paul Grimault and Lotte Reinenger are probably better candidates. Seems you can even go all the way back to the ancients, who painted “moving scenes” on jars and things, that are accepted as being animation in their own right. But I’m not concerned with such prehistoric examples, and in the course of my research since leaving this on hiatus in 2017 I've found it hard to come up with a definitive answer as to who is responsible for the birth of animation. Therefore I present these examples of men who can possibly be called

The Godfathers of Animation

Charles-Émile Reynaud (1844-1918)

Charles-Émile Reynaud (1844-1918)

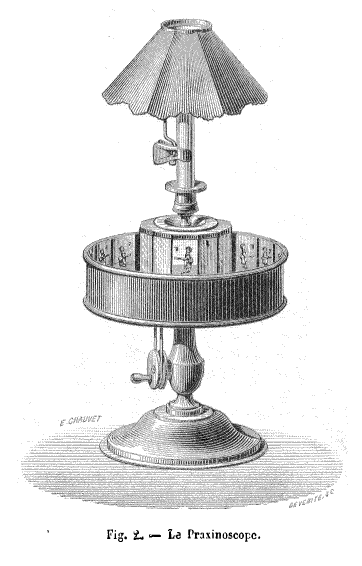

With an engineer for a father and an artist for a mother, Reynaud was perfectly placed to become one of the first animators, improving upon the zoetrope, a device that spun and showed painted figures which appeared to move as the watcher viewed them through slits cut in the cylinder, with his praxinoscope, which improved the design by replacing the simple slits with mirrors, making the images as they passed by more fluid and less distorted that those seen through the zoetrope. Originally sold as a very successful toy, Reynaud began to think about using it as a projector, by having a large screen in front of the praxinoscope, onto which he could project his “moving” figures. In essence, it seems this was the first example, almost, of a movie projector. However Reynaud failed to patent it and a few short years later the Lumière brothers created and patented the first real movie camera, the cinematograph, and that was the end of his invention.

The théâtre optique

Literally, the optical theatre, this was the improved version of Reynaud’s praxinoscope, the one with the ability to project the figures onto a screen. Reynaud’s first performance was for some select friends, and was called “Un Bon Bock” (a good beer) and they were so impressed by it that he then set up the théâtre optique. However the popularity of his machine turned out to be something of a two-edged sword. Two of its main drawbacks were that it was very fragile, and could easily break if not handled and treated properly, and in addition the only way to operate it was by hand, which meant that when Reynaud secured a contract with the Grévin Museum in 1892 for daily performances of the machine, he had to be there personally to turn the thing. Not quite sure why he couldn’t have paid someone else to do it, but that’s what it says. Maybe the museum wanted him to be there personally in case anyone had any questions, or maybe they didn’t (or he didn’t) trust anyone else to work the apparatus. Maybe it was just in the contract that it had to be him.

Whatever the reason, the Grévin also demanded new films every year, while a clause in the contract (did he not read it before signing such a draconian document?) prevented him from selling any of his films outside of France. The grind of being tied into this contract, all his time taken up literally turning the handle of the praxinoscope and coming up with new material for it, allied to the as already alluded to invention of the cinematograph, which was to make his machine obsolete only a few years later, all led to Reynaud testily dumping his films into the Seine, where they were destroyed. Sadly, nothing exists today except this one clip I was able to track down. It does, however, make the jaw drop when you see the techniques used and remember this was at the tail-end of the nineteenth century!

Sure. you can see through the figure and it’s obvious he’s made of paper, but look how he moves! Or seems to, I should say. Look how the brightly-painted figure of the woman appears to emerge from a door to the right and walk onto the “stage”. When Pierrot enters, he comes through a door that just appears in the wall, but it’s believable as an entrance. And the figures genuinely seem to interact with each other. Remember, these are just static drawings being projected on a screen. When the door opens there’s a square of light on the floor too, as if a real door had opened, and when the first figure we saw goes behind a pillar, he disappears completely, in that sort of animation-doesn’t-obey-the-laws-of-physics thing I talked about in the section on "Plane Crazy" and also on Felix, both of whom were almost thirty-five years later. Now the reconstruction shown in the video was admittedly a hundred years later, but you have to assume that all they did was restored it, not upgraded or updated it in any way, in which case it’s a stunning achievement for the time.

I think Reynaud has a good claim to being named the actual father of animation, though history precludes him from this as he was not ultimately successful, and was largely forgotten as the cinematograph took over and the Lumière brothers passed instead into the history books. At the heart of the unhappy inventor’s failure was the reliance on temperamental machinery that was very delicate, but more, the one-man-band idea, the artisan who worked alone. While the Lumières made a business out of their new machine, had it easily mass-produced and were able to show people how to use it, Reynaud, a true remnant of the nineteenth century compared to the forward-looking, almost futurist Lumières, laboured on alone and refused to involve big business or investors, and like all the “little guys” in every developing industry, he was crushed by the wheels of advancing technology. He died after a short spell in a hospice in 1917.

Remarkably, and perhaps giving Reynauld the last word from beyond the grave, the Lumière brothers declared “the cinema is an invention without any future”, which probably ranks right up there alongside “Can’t act, can’t sing. Can dance a little” (Sinatra) and “too ugly to become famous” (The Rolling Stones) with the most ill-advised reverse predictions ever made. The Lumières instead marketed their invention as a tool for photography, not film, and so are not considered, despite making the first real strides in the field of animation, to be its forebears, despite being credited with having invented the technology.

Arthur Melbourne-Cooper (1874-1961)

Arthur Melbourne-Cooper (1874-1961)

From what I can make out, the next milestone on the road to animation comes from the UK, from a guy called Arthur Melbourne-Cooper, the son of a photographer who created what is generally accepted as “the world’s first stop-motion film”. It was commissioned by Bryant and May, one of the biggest manufacturers of matches at the time, in response to an appeal to help the soldiers in the Boer War, who were struggling from a shortage of matches. You might imagine, far from home and fighting surely disease and heatstroke as well as an implacable enemy that the last thing on the minds of the soldiers was smoking, but when has that ever stopped a company getting what it wanted?

Using what would become a well-used method of filming one frame, moving the model slightly, filming again, moving it again etc, Melbourne-Cooper was able to make it seem as if the matches were animated, as two sticks figure made of them spelled out the appeal on a black wall. This all took place in 1899.

Now, let’s be clear and honest here. The voiceover on this video proudly claims “The oldest existing animated film in the world is British.” But no, it isn’t. Because as we’ve seen from our piece on our friend Charles-Emile Reynaud, a version of his

Pauvre Pierrot is still around, albeit in a restored form, and that predates “Matches Appeal” by a good seven years. But I suppose if Melbourne-Cooper’s one, being shot, obviously, in black and white, has survived without being restored or altered for over a hundred years, then maybe she has a point. Whatever the case, it’s an impressive little bit, both of animation and of advertising, pulling at the heart (and purse) strings of the viewer, both by dint of their patriotic fervour for “the boys abroad” and by the cuteness of the little stick figures. Well, I don’t think they’re cute but I bet many who watched that film did, and donated their guinea accordingly.

By 1908 Melbourne-Cooper had progressed in leaps and bounds (for the time) and had moved on to be able to shoot a live-action movie with stop-motion (or, as it was called at the time, frame-by-frame) animation in the fantasy short film “Dreams of Toyland”. In the movie, a woman takes her son to a toyshop, where a distinctly sinister-looking shopkeeper sells her some toys. In quite a clever move, one of the toys she buys, a large omnibus, has an advertisement on it proclaiming the title of the film. That’s all very well and good as far as it goes, but nothing terribly innovative. Yet.

It’s when the child goes to bed that things start to get interesting. Suddenly the scene zooms in, and we see the toys all arranged as if they’re in their own little city. People cross roads while horses and carts move along them and that big omnibus makes its slow way down the thoroughfare. One of the soft toys (think it might be a golliwog - wouldn’t be allowed these days!) - even drives the omnibus while other toys, including a white teddy bear, climb on board. However in helping I think a monkey on to the bus the bear overbalances and falls off the bus. Oh dear! But he’s not hurt (when ever is anyone in cartoons or animation, or when does it ever matter?) in fact he starts fighting with.. yes I’m sure that’s a golliwog. So you have a white bear fighting a toy notoriously recognised as a black person. Whether innocently or no, whether making a political/racial statement or just completely coincidentally, you have perhaps the first filmed occurrence of a race fight on screen!

Now it looks like the golliwog is stealing some drunk’s bag and running off, and then being tackled by a monkey. Are they fighting or dancing? If the former, there’s a very violent subtext to this film! Now a guy on stilts is joining in and - no, they’re all dancing now. Definitely dancing. And now they’ve been run over by the omnibus! Oh look! Here’s that troublesome white bear back, and he’s riding a train. And he’s, um, ramming a monkey in the arse with it. Now the monkey is on a horse chasing the bear and here comes the omnibus again and - it’s crashed into the bear, running him over and blowing up. Man, such violence and such a dark ending!

Amazing stuff, and if you’re totally into looking for subtexts like me, there’s racial violence, latent homosexual activity, just normal violence and road rage! Crazy. And all before World War I. Arthur Cooper-Melbourne was not just an animator, but made plenty of live-action films (as this one shows) and in fact opened two studios, one of which burned down, but that pesky war interrupted his schedule and though he made some animated advertisments for cinemas after the war, opening an ad agency, he retired in 1940 and died in 1961.

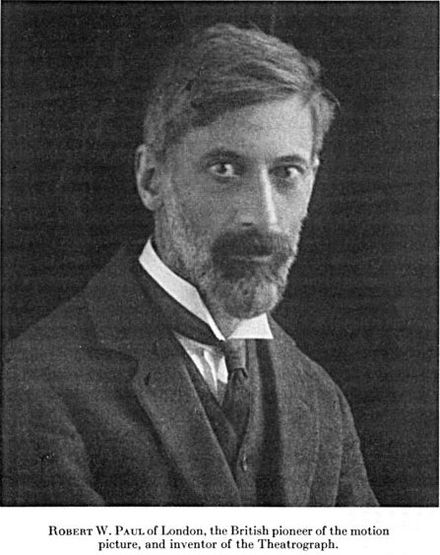

Walter Robert Booth (1869-1938) and Robert William Paul (1869-1943)

Walter Robert Booth (1869-1938) and Robert William Paul (1869-1943)

Interesting point above: these two men appear to have been born in the same year and died a mere five years apart, Paul slightly outlasting Booth. A cartoonist and conjurer, Booth teamed up with Paul, an inventor and showman, and together they produced a number of animated films, beginning with “Upside Down, or The Human Flies” in which Booth simply turned the camera upside-down to make it appear as if his subjects were on the ceiling. A simple trick, but back then it probably stumped audiences, and being a magician at heart, he probably played up to the idea that this was a form of magic.

It’s cleverly done, and let’s be honest: it’s actually more realistic and believable than Batman and Robin, some sixty years later, apparently walking up a wall! You know how this trick is done, yet in some ways you kind of forget that, and it looks very impressive. I’m not looking through the whole thing - it runs for over twelve minutes, and I’ve work to do - but I do see about halfway through a magician puts a woman in a sort of wardrobe and when he opens the door, first she’s gone, then she’s in a sort of Iron maiden thing, then she’s a skeleton, then she’s a man - very clever indeed. Ah, I see. Looking further I see whoever created this video has in fact joined that film and another called “The Haunted Curiosity Shop”, so that explains why it’s so long and why there was no mention of this cabinet trick in the piece about “The Human Flies”. Worth watching for both.

“Marley’s Ghost”, shown above, from 1901, was a Paul product, and though it’s essentially a movie, it does use clever early animation techniques, such as superimposing Marley’s ghostly face on Scrooge’s door, and also scenes from the miser’s childhood on a black curtain over his bed. Another of his, this time from five years later, shows a car driving up the wall of a building to escape a pursuing policeman, then fly across the sky, up into the clouds (along which it drives as if they were hills) and onto the moon (face and all) then on to Saturn, where it literally drives around the gas giant’s rings, falling off and plunging back to earth, where it smashes through the roof of the courthouse, from which it is pursued by the law until, caught, the driver has the car turn into a horse and cart, and the cops let it go. Whereupon, as it drives away, it turns back into a car.

Booth is probably best known, if at all, for his “scaremongering” animation trilogy, “The Airship Destroyer” (1909), “The Aerial Submarine” (1910) and “The Aerial Anarchists” (1911), the last of which predicted what might happen should terrorists gain control of aircraft, perhaps both a prophecy about the coming war and also a look almost a century into the future where the numbers 911 would take on a whole different, horrible and long-lasting meaning, and would in fact prove his “theory”.

The middle one is the only one I could track down, and again it’s more a film than a proper animation, but it does use clever techniques that would be used again and again in cartoons, such as the fake ocean seen through the portholes of the submarine by the captives as they travel beneath the water, complete with animated fish, the animation of a torpedo and an explosion as the sub torpedoes an ocean liner and a rather clever if crude flight as the sub leaves the sea and flies into the air. Interestingly too, it shows the development of photographic plates in the film, possibly (though I can’t confirm) the first time this process was captured on film.

I also remark on the fact here that the leader of the pirates, from what I can see, appears to be a woman. Considering this was 1910 and women’s suffrage was still a decade away, this is either a very bold move on Booth’s part, making a telling statement, or I guess could also be viewed as the belief that women on board ship are always bad luck. She must be the captain though, because as everyone else, including the hostages, scramble clear and run when the submarine crashes to earth, she folds her arms, remains in the hatchway and waits till the thing explodes, literally going down with her vessel.

Like many early animators and film-makers, Booth gave it all up in 1915 and got into the advertising business, where he invented a method called “Flashing Film Ads: unique colour effects in light and movement.” Paul had already moved on to other things by 1910, five years previous, but is remembered fondly by animators, and when you look at the work he put out that’s not at all surprising. But he had many irons in the fire, and neither cinematography nor animation were the ones he wanted to handle.