Timeline: 1976

The Soweto Uprising ( 16 June 1976)

Era:

Timeline: 1976

The Soweto Uprising ( 16 June 1976)

Era: Late twentieth century

Year: 1976

Campaign: None, as such, but essentially part of the fight against Apartheid, the struggle for the right to be treated with dignity and respect

Conflict: Apartheid

Country: South Africa

Region: Soweto, Johannesburg

Combatants: South African Police and black protesting students

Commander(s): (Students) Teboho "Tsietsi" MacDonald Mashinini (very nominally) Archbishop Desmond Tutu (Police - no name given of the commander so blame must fall on the heads of) Prime Minister (later State President) B.J. Vorster, Minister for Bantu Education J.G. Erasmus, Deputy Minister of Bantu Education Punt Janson. Probably the Minister of Justice too, but I can't find out who he was at the time.

Reason: A protest against the forced imposition of the Afrikaans language in schools

Objective: To force authorities to rethink their position and allow children to learn in their own native languages

Casualties: From 176 to 700

Objective Achieved? Yes

Victor: Technically, South African Police and State, though in the long term the protest (and the brutal crackdown) was seen as a watershed moment in South African politics and the beginning of the end of Apartheid

Legacy: A massacre that shocked even white South Africans, to say nothing of the world at large (even though we, as usual, made a lot of noise but did nothing) and which began the slow process of dismantling the system of Apartheid in South Africa, leading eventually to the triumphant release of Nelson Mandela.

Well, I said when I began this journal that it would not only focus on battles and wars, but all areas of human conflict, as it says in the title, and while this was not a battle as such - unarmed children against heavily-armoured police - it does cover one of the most shameful periods in man’s history, when too much innocent blood was shed for reasons of repression and racism.

To understand the reason behind this protest, and the resultant confrontation with police, it’s necessary to understand what apartheid was. Thankfully now, we can say this in the past tense, as when I was growing up apartheid was a factor of daily life for black South Africans, and we heard about it on the news all the time. With the eventual release of Nelson Mandela that all changed, but it took over thirty years for it to happen.

Apartheid: It Did Matter If You Were Black or White

Apartheid: It Did Matter If You Were Black or White

I have no intention of trying to write a treatise on the system of social and racial segregation instigated in South Africa for over four decades, as it would be both presumptuous of me, as a white, to try to do so, and, more importantly, would require almost another journal to cover it as it deserves to be. But I’ll do my best to quickly explain, for anyone who isn’t familiar with the term - and if so, thank god or the absence of a god that you are - what this entailed. As usual, it stemmed from the conquest and occupation of a country, in this case South Africa by the Dutch who, being largely white by ethnicity, regarded the natives as little more than slaves. The Dutch East India Company arrived in 1652, establishing a trading colony at the Cape of Good Hope, and members were allowed to settle and farm the land there, much to the anger and resentment of, and resistance by the native African tribes. Many of these settlers would end up fighting the British in the Boer Wars a few centuries later, as Britain took over the colony in 1798, having fought the French (now in control) for passage to India.

Britain’s abolition of slavery in South Africa in 1834 irked the Dutch settlers, the Boers, and their dislike for the natives led to their own Boer Republics around the Transvaal and the Orange Free State passing laws that promoted racial segregation. With the rise to power of the Afrikaaner-led National Party (Afrikaaners being mostly Boers and other whites) in 1948, the practice of apartheid, or separateness, was installed as policy, and South Africa came under white rule. As more and more anti-black laws were passed (The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act a year later, The Immorality Amendment of 1950, which expanded on the 1949 Act by prohibiting sexual relationships, not just marriage, between races, and the Population Registration Act of the same year, which officially and legally divided all South Africans into one of four groups - Black, White, Coloured and Indian) - the days of slavery were back in South Africa in all but name. Blacks lost the right to vote, to hold any sort of meaningful or well-paid job, were relegated to live in the poorest towns and villages, and were forbidden to run for any sort of public office.

Opposition, though, was growing against the regime during the 1970s and 1980s, led internally by Nelson Mandela’s Africa National Congress, though he himself was jailed in 1962, and the world constantly protested (although did not intervene), holding benefit concerts, placing embargos on South African imports and exports, and boycotting events there. Eventually, inevitably, the pressure would tell and the tide would turn, and Soweto was one of the events on which this seachange depended.

Dirty Rotten Afrikaants…

Dirty Rotten Afrikaants…

I suppose it would be similar to a country conquered by Nazi Germany being forced to use German as their only language, or the Roman Empire insisting everyone spoke Latin. It was the language of the enemy, the tongue of the oppressor, and while we Irish may have been pushed into speaking English as our own national language slowly died out, the South Africans weren’t standing for it and they protested. The trouble was that back in the bad old days of apartheid-driven South Africa, protests were not allowed, not by blacks, and were met with unbelievably disproportionate violence. White South Africans, especially the hated and feared South African Police, barely recognised blacks as human, and did not consider them to have any rights.

The Deputy Minister of Education pronounced the edict without any sort of consultation with the black community, even the respected Bishop Desmond Tutu spoke out against it, but the policy was to be installed in the schools and nobody was allowed to say anything against it. The Africa Teachers Association of South Africa objected to it on logical grounds, pointing out that few of the students even knew Afrikaans, so it was a language they would have to learn first, which would take the focus off their attention to the subject. Like learning maths in Spanish I guess, if you can’t speak Spanish. Ridiculous. But that was South Africa in the seventies for you. All about tightening the hold of white supremacy over the black population and removing the cultural and traditional supports they relied upon. English was also allowed as an acceptable alternative by the authorities, but this wasn’t much help as most of the indigenous population didn’t speak that either.

Faced with an intractable, uncaring government who wanted to stunt their educational development and further limit their almost laughable opportunities in this world run by the white man, students went on strike at Orlando West Junior School, refusing to go to school. This protest quickly spread, until the Soweto Students Representative Council met on June 13 1976 and organised a mass rally to make their voices heard. This was set for three days later, on June 16.

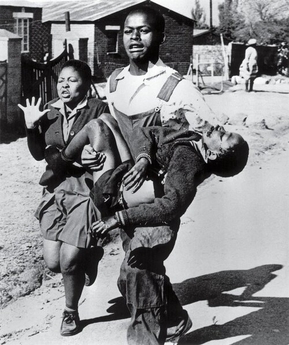

Load Up, Load Up, Load Up, With, um, Real Bullets

On the morning of June 16 an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 children, students and teachers began the march to the rally, but police, somehow aware of the event, blocked the road with barricades. Reluctant to provoke them, the protesters took another route, their numbers having dropped to from 10,000 to 3,000 by the time they reached the wellspring of the revolt, Orlando West Junior School. As the peaceful protesters chanted slogans and demanded equal treatment, police turned their dogs loose on the crowd. The protesters killed the dogs, and the police began to shoot.

Okay, let me just make that very clear, because in these days of more enlightened thinking it’s almost impossible to contemplate such a thing, but yes, the South African Police, facing a crowd of protesters, most of which were children of school-going age, opened fire. With live ammunition.

One more time, in case you don’t get it.

Police. Shot. And killed.

Children.

As panic swept through the crowd and it began to break up, the police kept shooting, until 23 people lay dead. That night, violence erupted as shops and government buildings were targeted, and the police responded with lethal force. By the end, estimates of deaths range from 176 to 700, with thousands wounded. A measure of the arrogance and ignorance of the apartheid regime for blacks was an order sent by the South African Police to the hospitals for the names of any wounded found to have bullet holes in them to be sent to them, so that they could later prosecute them for rioting! Thankfully, doctors treated this request/order with the contempt it was due, and no names were passed back to them.

Legacy

There are always watershed moments that can lead to revolution, and it’s usually a case of the oppressed being pushed just too far, and deciding they’re no longer going to take it. In America, the former colony was furious at the government tax on tea, and this led to the American War of Independence, resulting in the creation of the United States of America, a huge step towards breaking England’s status as a major power. In Ireland, the Easter Rising quickly led to the establishment of the Irish Free State, and here the Soweto Uprising stunned people with the force of the ferocity and inhumanity with which it was put down. Central to the problems that began to beset the South African government was that even white people were outraged, and a day later white students marched in protest. They couldn’t be shot and cowed into submission, and as other black townships rebelled, international pressure on the regime grew and the stranglehold of the National Party began to slip, and the Rand devalued in the wake of economic depression, the troubled and bloody walk towards a new and brighter horizon had begun.

The massacre also helped the ANC to rise as a real force for protest and change, as student rallies and protests were coordinated under its banner, strikes organised and resistance channelled through their offices, but a slow and painful march it would be. Ten years later police would again massacre up to 25 people in a raid intended to evict them for non-payment of rent, and tear gas would later be dropped on mourners at a mass funeral for these same victims. The USA, meanwhile, making plenty of noise from the safety of the White House, declined the opportunity to bring up the Soweto massacre when Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met President B.J. Vorster a week afterwards in Germany, steering well clear of the subject. I guess with the US’s record on civil rights, even now, he may have felt that was a step too close towards the pot conversing with the kettle about its colour.

It would take another fourteen years before Mandela would be freed, in a new climate of change and (kind of) acceptance of the rights of blacks, and indeed he would go on to become South Africa’s first black president, dying in 2013, having experienced a mere thirteen years freedom. June 16 is now forever commemorated as Youth Day, a holiday in South Africa, honouring and remembering the children and youths who died at Soweto.

Why will this conflict be remembered?

How could it not? It may not have been the first time, but it’s the first time I ever heard of armed police opening fire on children. They may have shot unarmed protesters before, probably did, but I think shooting children brought the apartheid regime to a new low, and it could really sink no lower. Nevertheless, it seems the government did not learn its lesson easily or quickly, as related above with another massacre in 1986. However the tide was turning by then, and four short years (not to him, I’m sure, but in relative terms) later Nelson Mandela would secure his freedom and walk from Robben Island a national hero and icon. It all started with a bunch of kids who decided they’d had enough, and took on a gargantuan, immovable relic of their past which clung grimly and determinedly to power as the world changed around it, and took the unthinkable final step that would eventually bring it crashing down in the dust.

Suffer the children, indeed. Lends new and chilling meaning to the words from the Bible, “and a child shall lead them.”