Red, White and… Green? The influence of the French Revolution and the American War of Independence on the Irish Rising

Red, White and… Green? The influence of the French Revolution and the American War of Independence on the Irish Rising

I noted elsewhere in this article that had Catholics been granted the same rights as Protestants in Ireland, there would have been little appetite for any sort of rebellion. Overall, Irish people didn’t seem to have a problem with being ruled by an English king, just one who oppressed them on the grounds of their religion. So up until about now, the mid to late eighteenth century, I see no moves towards gaining independence for Ireland. But with the French Revolution seeming, on the face of it, so successful, and with the breaking away of the American colonies from the iron and unfair grip of the king, to say nothing of the Polish Constitution passed in 1791, it must have looked to the United Irishmen as if Ireland had a chance. England had been weakened by its war with America (both in manpower and, more importantly, in its reputation as one of the superpowers of the eighteenth century) and the French, initially at least, were fellow Catholics.

I’m sure it wasn’t that glib or simple that the Irish just thought, sure why not, let’s give it a go, but the time must have seemed opportune to press their cause. In other ways, it might have been the worst possible time. Fuming at his defeat in America, worried over the expanding reach of the new French Republic, which had just taken Rome and captured the Pope, King George III might have been in no mood to take s

hit from a load of piss-poor Catholics and assorted what he would have considered traitors. While it’s unlikely he was spoiling for a fight, you could make the argument that he might have relished the chance to bolster back up his reputation, take out his frustration at being kicked out of America, and ready too to show the French they weren’t going to have it all their own way, that Britain was still, despite what they might have heard, a force to be reckoned with.

Of course, I could equally be talking complete bollocks. I’m no historian and these conclusions or guesses are not based on anything other than my own reading of the situation, which may be way off. Maybe the Irish just decided they’d had enough with being ruled by kings and queens. They’d tried unsuccessfully for centuries to sponsor the rise of a Catholic monarch to the English throne, and even when their prayers were answered, he was still a bastard to them. So it’s possible they said, Catholic or Protestant king? You know what? We’ll have none of the above. And decided it was time to be their own masters.

His Majesty, of course, had other ideas on that score.

Land of Spies and Snitches: Turncoats and Traitors of the Rising

Land of Spies and Snitches: Turncoats and Traitors of the Rising

Not every Irishman was dedicated to the overthrow of British rule over Ireland, it would seem, and as in so many instances down through our history, there was a line of people willing to sell out their comrades for either amnesty, money or both; people who betrayed Ireland at a time when, had it not been for their cowardice and treachery, we might have had a chance of winning our independence, something we would now have to wait a further 150 years for.

According to Brendan O' Cathaoir, writing in

The Irish Times in 2004, Irishmen were not the best at keeping secrets in the first place, and while there were plenty ready to sell them out, some of their own talk may have sealed the fate of many. The idea of a quiet Irishman in a pub - particularly a fired-up, oppressed, English-hating would-be rebel, is hard to imagine, if such a creature existed. So some of the secret plans of the United Irishmen were doubtless loudly proclaimed in drinking establishments, boasted of, used as threats and forecasts of things to come, and surely reached the ears of those who should not have heard of such things.

All of that notwithstanding though, let’s look at some of the people who were instrumental in thwarting the first real attempt by Ireland to throw off her shackles and free her people.

Leonard McNally (1752 - 1820)

Leonard McNally (1752 - 1820)

Probably not fair to call him a supergrass, as that referred more to a turncoat, someone captured for committing crime (usually of a paramilitary kind) and who turned informer for money. Supergrass was an expansion on the term grass, which has two proposed origins, one being that it comes from grasshopper, which is said to be Cockney rhyming slang for copper (though I’ve never heard of anyone using that term) and the other refers to the traditional snake in the grass, denoting a traitor. Whichever story is true, while McNally may not have been a supergrass he certainly was a grass, a spy who worked for the British government and betrayed his comrades in the United Irishmen.

A barrister by trade, McNally took it one step further, collaborating with the prosecution while ostensibly conducting the prisoner’s defence, to ensure a conviction. It does appear though that he didn’t join the United Irishmen intending to betray them (from all accounts and as far as I can gather) but was spooked by the betrayal of Reverend Jackson as he and Wolfe Tone discussed a French invasion of Ireland. He obviously found it profitable then to use his position in the organisation, of which he was a founder member, to pass secrets back to the British and ensure the coming rebellion failed. There’s no record of his having been pressured or threatened to do this, so whether he had intended to become a spy or it just happened, he’s still a bastard and his name reviled here in Ireland.

Seems he was never caught, either. His treachery (or patriotism I guess, depending on which side of the conflict you’re on) only came to light after his death.

Edward John Newell (1771 - 1798)

Edward John Newell (1771 - 1798)

Possibly the worst and most prolific informer who did more to turn in rebels during and after the rebellion, Newell started out of course as a member of the United Irishmen, though originally he had tried to hold down various jobs, the longest being as a painter and glazier, his naturally fractious nature leading to his parting with his employer after two years. He did spend nearly a year at sea, but in the eighteenth century that could be almost just one voyage, so it’s no great indication that he took to the life of a sailor.

It’s not clear whether he joined the United Irishmen in order to inform on them, whether he felt pushed into it by circumstances or whether he just changed loyalties, but he became an invaluable spy for Dublin Castle. His preferred method seemed to be to accompany a squad of soldiers through villages and towns (suitably disguised) and point out rebels, who would later be arrested. He boasted in his autobiography, rather provocatively titled

The Life and Confessions of Newell, the Informer, that he had sent 227 men into the tender mercies of the British government, for which he says he was paid £2,000.

Unlike McNally though he did not survive the rebellion, being assassinated (it is said, and only expected too) by the United Irishmen as he made plans to escape by sea to America. Bones found on the beach at Ballyholme in Bangor, Co, Down in 1828 were said to be his, indicating he may have drowned - or more likely, been drowned or thrown into the sea there.

There were even

female traitors and spies…

Bridget Dolan (1777 - )

Bridget Dolan (1777 - )

Perhaps the quintessential Irish tomboy, Bridget mixed with boys and learned to ride, a skill which would stand her in good stead when it came to taking part in the rebellion, which she did, riding on raiding trips and possibly reconnaissance ones too. In the rebellion, women were used as couriers, nurses, to carry supplies and carry messages and information to the men. Bridget was different. At Kilballyowen she took part in the ambush of a military supply convoy, setting the baggage car on fire. She later turned traitor though, selling out her comrades to the English and bearing witness against them in their trials after the rebellion was crushed (what? I told you that already).

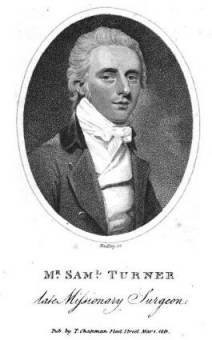

Samuel Turner (1765 - 1807)

Samuel Turner (1765 - 1807)

Appropriately named indeed! With aliases such as “Richardson” and “Fumes” he betrayed the United Irishmen, having been captured as part of their executive just prior to the rising, and was paid afterwards a pension from the British government. He it was who passed the information to the British that Lord Edward Fitzgerald and Arthur O’Connor were meeting in Hamburg to secure support for the rebellion. It’s said he died in a duel in the Isle of Man. He is however another one whose treachery was never uncovered while he lived, and he enjoyed the reputation of an Irish patriot, even sharing the company of later freedom fighter Daniel O’Connell.

Francis Higgins

Francis Higgins

One of four editors of supposedly nationalist newspapers and journals which paid obeisance to Dublin Castle and in addition informed on the Irish rebels, Higgins ran the so-called

Freeman’s Journal, and was in fact a kind of handler or spymaster, controlling, among others, Francis Magan, who as we saw betrayed Lord Edward Fitzgerald. He was known as “the sham squire”, due to his actions in securing a bride through the agency of forged documents which portrayed him falsely as a wealthy landowner, his wife fleeing in the wake of the discovery of his treachery, and her father taking an action against him which landed him in jail. After a further fraud returned him behind bars Higgins fell in with the owner of a pub and gambling den, Charles Reilly, from whom he assumed ownership of both it and Reilly’s wife until her death, after which he turned the pub into a brothel.

In perhaps an attempt to go a bit more legitimate (and in so doing increase his rather low standing in Irish society) Higgins next got into the clothing trade, then became a barrister and finally had a chance to buy a share in, and then buy outright the newspaper mentioned above,

The Freeman’s Journal. He made most of his profit from contracts received from the British government, and was happy to work for them, employing a network of spies which grew to a complement of seven at its height. In 1801 he received an annual pension from the government of £300 a year but died a year later.

Thomas Reynolds (1771 - )

Born a Catholic, he originally support the Catholic Convention of 1792, but later became more cautious and converted to Protestantism. He married a sister of Theobald Wolfe Tone’s wife, and joined the United Irishmen, ironically at the invitation of the man he was to betray, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, becoming its treasurer and given the rank of colonel. According to his own statement, when he realised how violent the rebellion was to be, he turned against them and informed Dublin Castle where the ruling council known as the Directory (surely as a nod to the same assemblage in France) could be found, leading to their arrest.

Having retired to his castle in Kilkea, he was more than surprised, as a government agent, to find it attacked and destroyed by British forces. In his biography

Life of Thomas Reynolds, 1839, his son recounts the destruction of the castle:

“It has been my father’s lot since then to witness the ravages of war in the peninsula, where Spanish, French, Portuguese and English, with their German auxiliaries, men trained to rapine, alternately plundered and devastated the country; but in all that disorder of which he was an eye-witness for six years, he has frequently assured me that he never saw such cold-blooded, wanton, useless destruction as was committed [by the King’s troops] at Kilkea and the surrounding country.”

After repeated attempts to kill him, he eventually sought the protection of Dublin Castle, declaring himself firmly on the side of the British, was given lodging there and gave evidence against his former comrades. He later left Ireland and went to Lisbon, Iceland and eventually died in Paris in 1836 at the age of 65.