It’s always a little hard to take anything anyone says about themselves in a positive light at face value, and you’d have to wonder at the almost superhero-like account Goering gives here of one of his squadron’s hardest (and in real terms, least believable) dogfights, but if nothing else it’s entertaining, so here it is reproduced in full from Peter Kilduff’s fine

Herman Goering - Fighter Ace: The World War I Career of Germany’s Most Infamous Airman:

'Again it is a clear June day in the year 1917, not even a small cloud in the heavens. In the early morning hours, I gathered my officers and pilots about me and impressed on them all of the regulations about flying and fighting as a formation. Then I assigned each one his place in the formation and gave the final orders. I believed the new Staffel to have been sufficiently trained and I firmly decided to lead them into battle this day and .. . let them show proof of it. 'Soon after take-off the formation was assembled and we set out in the direction of the frontlines. In order to fly and fight in a more mobile way, I had the Staffel separated into two flights of five units each. I led the lower one and the upper one had to stay closely above us and follow. In the sector from Lens to Lille a relative calmness prevailed. From time to time a lone artillery spotter aeroplane moved about with great effort far behind its own lines. We flew on and on northward towarj our chief objective, the Wytschaete Salient. 'When we arrived at Ypres, we were at 5,000 metres altitude. A marvellous view of Flanders was spread out below us.

In the distant background gleamed the coast of France, stretched along the sea; we could clearly recognise Dunkerque and Boulogne; we knew that in the pale mist at the end of the horizon were the chalk cliffs of the British Isles. Below us lay Ypres and the enemy positions, which were situated around the heavily shelled city in a salient opening to the west. To the north the Flanders coast stretched on from Ostende to the mouth of the Schelde river. The Schelde itself glistened in the sunshine on to Holland. From 5,000 metres the eye took in a view of this piece of the earth, above which arched the sky in light blue. 'But danger also lurked here and we had to ... examine everything carefully. A sudden flash in the sun could betray us or the enemy. Despite having dark-green lenses in our goggles it was difficult to make out objects in the blinding flood of sunlight ... Just then I recognized that six enemy fighter aircraft were above us and ... flying with us. Blue-white-red cockades clearly shone on their silver-grey wings. Yet they did not attack us, as we were too many for them; they simply followed at an ominously close distance. For the present, we .. . could do nothing other than be careful.

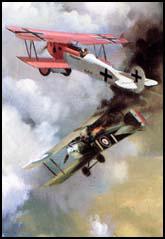

Then I sighted more opponents. A formation of enemy Spad single-seaters approached from the rear left, another of [Sopwith] Triplanes from ahead on the left, both still some kilometres away, but heading towards us. At this moment, coming from in front of us, there suddenly appeared a squadron of British Sopwith [Pup biplane] single-seat fighters. Now they had to be dealt with. If I were to attack them, I would immediately have the six Nieuports soaring over us and down on our necks and a few minutes later both of the other enemy formations would be rushing toward us, as well . If I were to avoid them, then I must abandon the frontlines altogether, and the airspace would be free for the Englishman; he could do whatever he wanted over our lines. 'I decided to attack immediately, no matter what the cost. Now everyone had to show what he could do and what he was good for. There was no longer any thought of retreat; we had started a fight against a force four times greater than ours, now we battled desperately for our survival. This is how I wished to put the Staffel to the test. The aerial battle was upon us.

I gave the signal to attack - nosed over steeply with my machine - and charged into the Sopwiths. Immediately, they dispersed and the field of combat went downwards. There was wild firing all around me. From all sides you could see smoke trails of one's own and enemy incendiary bullets; tracer ammunition flew past me. Machines turned wildly, reared up, dived down, and looped. The enemy had now thrown himself into the battle in full strength; we duelled against thirty to forty enemy single-seaters. The greatest danger was [that we would] ram into each other. I sat behind a Sopwith that tried to elude my field of fire by desperately twisting and turning. I pushed him down ever lower as we came ever closer to enemy territory. I believed I would surely shoot him down, as he had taken some hard hits, when a furious hail of machine-gun fire opened up behind me. As I looked around, I saw only cockades; three opponents were on my neck, firing everything they had at me. Once again, with a short thrust, I tried to finish off the badly shot-up opponent ahead of me. It was too late. Smack after smack the shots from behil1ct. hit my machine. Metal fragments flew all around, the radiator was shot through; from a hole as big as a fist I was sprayed in the face by a heavy stream of hot water. Despite all that, I pulled the machine about and upwards and fired off a stream of bullets at the first fellow I saw. Surprised, he went into a spin. I caught up with the next opponent and went at him desperately, for I had to fight my way back across the lines. He also ceased fighting. It was a decisive moment. My engine, which was no longer receiving water from the radiator, quit and with that any further fighting by me was over. 'In a glide I passed over the lines and our positions. Close behind them I had to make a forced landing in a meadow.

The landing proved to be a smooth one, and the machine stayed upright. Now I sawall of the damage. My worthy bird had received twenty hits, some of them very close to my body. I looked around me apprehensively; what had happened to my Staffel? There was a noise above me and shortly thereafter one of my pilots landed in the same meadow. His machine looked pretty bad too; various parts were shot to pieces. Another two pilots also had to make forced landings with shot-up machines. But the pilots were safe and sound. The Staffel had prevailed in the toughest battle. Despite its numerical superiority, the enemy had quit the field of battle. Everything had been observed from down below and we reaped our rewards of recognition. Far more important for me, however, was the feeling that I could depend on my Staffel. During this violent Flanders battle the Staffel had delivered on what it had promised on one fine June day - to fight and to be victorious.

Right. Sounds fanciful at best. An enemy force FOUR TIMES the size of Goering’s and they not only beat them off, shot some of them down, but ALL survived? Pull the other one,

kamerad, it’s got bells on! Still, there seems to be a general consensus that, despite what he became, Goering was feted as a pilot in the First World War, and, like Hitler, acquitted himself well in the conflict, however much we might wish to think differently. It was the job of the Nazis to rewrite history; it certainly is not mine, and grudgingly though I may give it, I’ll afford credit where it is due, even to men who later became monsters.

I must however remark on the huge difference in attitudes between the two wars, at least among airmen. Goering speaks of an English (actually Australian, but flying for the Royal Flying Corps) pilot he duelled with, eventually overcame and forced down. When the Englishman (sic) was taken prisoner, Goering spoke to him and they conversed about their dogfight, each congratulating the other on his skill. Knights of the air, indeed! By the time Hitler came to power such “gentlemanly conduct”, such “sporting behaviour” was long gone, even if the speed and power of the aircraft now made it far more likely that the loser was going to die in a ball of flame rather than just be forced down. World War I may have been, in essence, more brutal and savage than its later cousin, but in terms of air warfare and the conduct attending same, it could be said to have been the last “civilised war”. Hitler and the Nazis were not interested in recognising the valour of the opponent; to them, they were an inferior enemy, worthy of nothing more than death or capture. Airmen taken prisoner in World War I were treated well, and officers afforded much honour; in World War II everyone was treated the same.

If the writing is his, and not embellished by later biographers and Nazi revisionists, I must compliment Goering on his prose. It’s quite elegant, as you can see from any of the extracts published above, almost more like poetry or literature than mere reports or accounts. Some very descriptive passages whcih would not be out of place in a novel. However we must not forget that he was not only a Nazi, but one of those in high command, a confidante and friend of Hitler, and like all at least high-ranking Nazis, a rabid anti-semite. This is shown by his slur against one of his own officers in 1917, Lt. Willy Rosenstein, necessitating that officer’s demand he rescind the slur, and on Goering’s refusal to do so, Rosenstein’s request, which was granted, to be transferred. The thing is, reading about his air combat stories you can’t avoid a little grudging respect for the man, but always lurking behind Goering the World War One fighter ace, the hero of many dogfights, is the shadow of Goering the Nazi, Goering the cruel, anti-semite, the luster after power, the trampler on the careers, feelings, property and even lives of others, and Goering who, in the end, proved Goering the coward, taking his own life rather than face the hangman’s noose.

Further evidence not only of the man’s duplicity, but of the typical entitled officer’s attitude to money is seen when he attempted to claim back expenses incurred on his trip back to Mauterndorf in January. He erroneously - falsely, a blatant lie - described the fortress home of his uncle as a health resort, when it was no such thing, and surely had more than enough funds of his own for the trip, not to mention that his uncle was hardly likely to charge him for staying there. Just mean and greedy, two traits which would become apparent as part of his psychological makeup as he grew older and, becoming more powerful and in more authority, more dangerous. There exists, interestingly, no record of his receiving reimbursements, so it doesn’t look as if his little ploy worked.