Wanted: Dead or Alive

Wanted: Dead or Alive

It’s interesting to note that there was a very good reason why this condition was often appended to notices seeking the apprehension of fugitives from justice. Like I said, up almost to the turn of the century marshals worked for a fee, and in general this turned out to be about two dollars per head per captive, which they would be paid upon returning with the prisoner(s). But unless the wanted notice had stipulated “dead or alive”, should they bring in any of the criminals dead, they would not be paid. This probably showed how desperate states were to catch, or have killed, certain desperate characters: a marshal who knew he was not getting anything for a dead man would be mighty careful to ensure he arrived back at the jail in one piece and breathing, even if he may have had a chance to shoot him. If it was a “dead or alive” situation, on the other hand, well, prisoners are a lot less trouble when they’re dead, I expect, so this might be why it was never “alive or dead”, so that the first thing in a posse’s mind was, kill the bastard: hell, you’ll still get paid the two dollars, so why bother bringing him in alive? A sort of early form of subliminal messaging, perhaps, or a tacit approval of terminate with extreme prejudice?

As a representative of the US Government, a marshal could also try criminals if there was no judge present. As we’ll see a little further on, judges did not live in towns, but travelled around (perhaps the origin of the circuit court? Perhaps not; we’ll find out) and served a wide area, so the chances of there being a judge in town at the right time was, let’s say slim. In that case, the marshal could deputise witnesses, hire a place as a courtroom (maybe a schoolhouse, saloon, house, I don’t know: I’m learning this as I’m writing it and some of this is guesswork, to be confirmed or corrected later) and act as the judge in the case, dispensing justice to his prisoners. Whether that included hanging I don’t know, but I would think not. If the offence was that severe, maybe the prisoner(s) would have to be taken to wherever the judge was sitting. The case I read about involved a marshal fining thieves, so I expect he had some latitude but not unlimited powers. He was, after all, an officer of the law and not above it.

You probably have heard in movies the word marshal and sheriff being used to more or less describe the same official, and the guy referred to had nothing to do with the tough lawmen we just spoke about. Called town marshals, these were in fact a step below the sheriff, who was usually responsible for the entire county, whereas this marshal, as you might have guessed from his title, took care of the town he was in and no more. Mostly he was a sort of functionary: collecting fees and taxes, maintaining the town jail, running health, fire and sanitation checks, keeping records and offering evidence at court hearings.

And then, there were the Rangers.

Most will have heard of the Texas Rangers, but Arizona and New Mexico had them too. These were kind of the top guns of law enforcement, at least in the southeast, where their powers were vast and where justice meted out by them could be swift and often brutal. As Captain Burt Mossman of the Arizona Rangers put it:

If they come along easy, everything will be all right. If they don't,

well, I guess we can make pretty short work of them. I know most

of them and the life those fellows are leading in the mesquite shrub

to keep out of reach of the law is a dog's life. They ought to thank

me for giving them a chance to come in and take their medicine.

Some of them will object, of course. They'll probably try a little

gunplay as a bluff, but I shoot fairly well myself, and the boys who

back me up are handy enough with their guns. Any rustler who

wants to yank on the rope and kick up trouble will find he's up

against it.

Sounds like something out of a cowboy movie, but no, that’s an actual quote. Shows how tough and determined these men were. Even today, Texas Rangers still operate in that state and are feared as the oil state’s most indefatigable lawmen. Nevertheless, one of their first and most famous captains, John “Rip” Ford, who later went on to the US Senate and served as the mayor of Brownsville, had a slightly different view of his force:

A large proportion ... were unmarried. A few of them drank intoxicating liquors. Still, it was a company of sober and brave men. They knew their duty and they did it. While in a town they made no braggadocio demonstration. They did not gallop through the streets, shoot, and yell. They had a specie of moral discipline which developed moral courage. They did right because it was right.

Cold Justice: Law in the Frozen North

Cold Justice: Law in the Frozen North

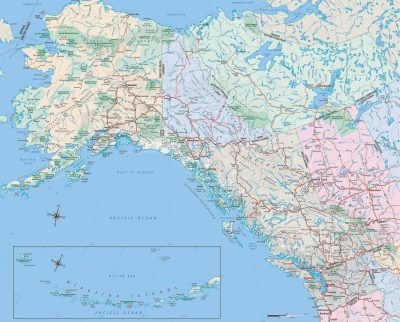

Look at the size of Alaska. Just look at it. And now figure in that around the time of the Klond

yke Gold Rush (1896) the entire territory had

one judge,

one marshal and ten deputies to enforce law. Further north, in Canada, the Yukon, there were the Mounties, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but as miners and speculators teemed across Alaska in search of gold, keeping law and order in that cold wilderness required firm and often deadly action.

When there weren’t enough law enforcement officers to cover a case, bounty hunters might be used to supplement the force, and also detectives. Although the idea of a detective was quite new in the world during the latter half of the nineteenth century, in America the Pinkerton Detective Agency was set up and became known for their dogged, unflagging pursuit of criminals. They also provided security on trains against robberies, often taking would-be bandits by surprise, as the Pinkertons wore no uniform and could easily blend into the crowd, passing for passengers.

Hang ‘em High: Lynchings and Vigilante Justice

Hang ‘em High: Lynchings and Vigilante Justice

We spoke briefly about vigilantes before, and to be honest, the two words don’t go very well together, as vigilantes, usually at the head of a mob, seldom wanted justice but revenge. To these people, the laws either protected the criminal when they should have dealt out swift justice to him instead, or just didn’t allow the wheels of justice to turn quickly enough. When this happened, tempers boiled over, patience snapped and hotheads led fuming crowds to jailhouses or in pursuit of men who were seen to have evaded justice. The usual end of such a journey for the accused was kicking his heels in the air while he dangled from a rope.

I should clearly make the distinction here between vigilante justice and lynch mobs. The former did allow a semblance of trial, with the prisoner’s crimes read to him and even a defence allowed, whereas with lynch mobs it was a straight, direct path to the hanging tree, with none of that annoying due process getting in the way. Lynchings were not sanctioned by law, but some territories turned a blind eye if feelings were running high enough. However lynch mobs had no real authority, other than their own, and were sometimes subsequently prosecuted for taking the law into their own hands, whereas vigilantes had often tacit, unspoken approval from the town or city authorities.

In vigilante justice, the mob’s rule might be more easily accepted, or acceded to, as these were clearly the prevalent feelings and few sheriffs or marshals would dare to go against the general mood of the town. They also might unofficially see them as a blessing in disguise, so to speak. For one thing, these folks had most likely only carried out the sentence the guy was going to get anyway, and in the process had saved the courts and therefore the government money.

One place vigilante justice began to come really into its own was along the route of the transcontinental railroad. As towns began to spring up along the line, there was no formal authority and so men would band together to keep law and order, using a variant of the old miners’ law to prosecute those who had sinned against the town, mine or railroad.

In terms of lynch mob justice, here’s a story (two really, but linked) that really illustrates the phrase “damned if you do, damned if you don’t”. A man accused of killing two lawmen, Charley Burris, was being transported to jail from Laramie to Rawlins, was taken from the train when it stopped in Carbon and a confession demanded of him. He refused, so they hung him from a telegraph pole. One year later another killer, “Big Nose” George Parrot took the same trip for the same crime and was stopped - perhaps by the same mob - in the same station. He too was asked to confess, but whether he had heard of Burris’s fate or not, he took the option to make a clean breast of it, and was allowed to continue on to Rawlins, where he was sentenced to be hanged. But when he tried to escape, a mob (again, maybe the same one: maybe they had followed him for the trial to make sure he didn’t retract his confession?) dragged him from the jail and hanged him. So no matter what he did, George Parrot’s destiny lay at the end of a rope. Maybe he would have been better just getting it over with at Carbon.

On that occasion it seems the mob either overpowered the sheriff and his deputies, who were holding Parrot, or else the law officers were powerless to - or reluctant to stop them. However on occasion lynch justice was openly approved by the federal marshals. Candy Mouton tells us of another interesting example when, in Aurora, Nevada in 1864, the hanging of six men accused of killing thirty settlers went ahead under the watchful eye of the US Marshal, Bob Howland, despite the governor being alerted to the illegal lynching by a concerned citizen. The marshal reported back to the governor that it was “All quiet in Aurora. Four men to be hanged in fifteen minutes.”

There were also what was known as range detectives. These men were employed by the railroad, stagecoach companies and cattle barons to protect their interests, with deadly force if need be. You might be surprised to learn that legendary gunfighter William H. Bonney, alias Billy the Kid, was a range detective himself. He worked for the Regulators, who kept the interests of rancher John Henry Tunstall as their top priority. Range detectives were highly paid for the time - sometimes clearing as much as 150 or 200 dollars a month (this in a time when, remember, the bounty on a live outlaw was two dollars and hotel rooms asked a few cents for a night’s board), and had to be good fighters. The deadlier the reputation, the less likely anyone would mess with them, though Billy’s rep did not stop the Lincoln County War from breaking out, but that’s another story, for another time.

Range detectives worked first and only for their employers, If they got into trouble with local or even federal law enforcement while carrying out the orders of their bosses, they relied on those bosses to smooth things out for them with the authorities, whether with bribes, threats or via their connections in high places. Pat Garret was also a range detective, as was Tom Horn.

Justice on Tour: Judges in the Old West

Justice on Tour: Judges in the Old West

As I correctly surmised earlier, the phrase circuit court comes from the time of the Old West, when judges were basically of no fixed abode, almost like itinerant pedlars dispensing justice and punishment, or perhaps innocence and freedom, as they travelled across their territory. Each judge was responsible for a large area, as already mentioned, and this meant he was constantly on the move, going from town to town and city to city, a real case of bringing Mohammed to the mountain. A judge would arrive in a town or district, hear all the cases that had built up over the length of time since he had been there last (excepting, I assume, any which had been dealt with by the expedient of summary justice, by vigilantes or by lynch mobs, or that the sheriff or marshal could deal with himself) and then travel on to the next town. If a crime was committed the next day, tough: you’d have to wait till he managed to fit you into his schedule again, and that could be months, months you would spend most likely in the county jail awaiting the chance to have your trial.

Not only that, but while as a defendant you had the right to be tried by a jury of your peers, given the short amount of time His Honour would likely be in town before ridin’ on into the sunset of justice, the chances of cobbling together twelve good men and true (or even twelve all right men who might occasionally play fast and loose with the truth) were slim, and what happened then? I really don’t know. Whether the trial then got delayed until a jury could be assembled (and if that meant not before the judge left town you might end up back in a cell to await his later pleasure) or whether it went ahead with what they had, or even without a jury, isn’t related in what I read. However it does appear that up until 1889 all a judge’s decisions were final, as there was no official appeal procedure, but after that the way was clear for convicted felons to appeal their sentence to the US Supreme Court, and thus I guess began the often ludicrous back-and-forth that attends trials even today, particularly in the case of the death penalty.