No matter what age we are, I think it’s fair to say that almost all of us have grown up with comics. For most of us, they may have been our first introduction to reading, out of school. Technically speaking, the kind of comics I read at ages 7 - 9 say would not really qualify as reading: they had little dialogue beyond sound effects and a few words or explanations, and mostly I read them for the pictures. It was like a cartoon printed on paper (which is essentially what it was, really), a way to follow the action via pictures with some incidental words you didn’t have to bother too much with. Not the best way to be introduced to reading, certainly, but you kind of learned despite yourself. Certain words became known to you, and how certain phrases led to certain actions. Minimal stuff - we read them for fun, not to educate ourselves - but it was a start.

Like most kids my age, my first comics all dealt with funny, slapstick or way-out themes. I remember one in particular called

Odd Ball, which was, if I recall, the adventures of a sentient ball, and another called

Creature Teacher, concerning the efforts of a monster to teach a class of kids, for some reason. I remember he only had one eye. On a stalk. It was weird and of course it made no sense, but then that was the whole point with comics at that age: they didn’t have to make sense. They were usually better if they didn’t. Which is, I guess, why some parents looked down on them, and why older kids might disparage younger ones for reading such nonsense, when they themselves had moved onto more mature comics.

Mostly, my childhood consisted of reading about the exploits of characters like

The Bash Street Kids, Desperate Dan, Korky the Cat, Billy Whizz and, of course,

Dennis the Menace. These stories (such as they were) were harmless, anarchic in their way, as the kid figure(s) usually spent their time hassling or getting in trouble with adult figures, and usually losing. You could say the comics such as

Whizzer and Chips, The Beano, Dandy and

Beezer taught disrespect from an early age, but again it was mostly harmless, to quote Douglas Adams. It was all in good fun and there was usually a moral, this quite often being a simple message not to misbehave. Of course, this was mostly a boy’s market: comics were marketed to girls, but they were simpler - possibly more adult really - concentrating on boys, romance, perhaps fairy tales, that sort of thing. To my knowledge there never was a “funny” comic aimed at girls. I could find out soon enough that I’m wrong, of course - and equally obviously, I’m talking about the market here, in Ireland, or really the UK, as we did not have our own comics and relied on English imports - but I don’t remember my sister for instance reading anything like I did when a young age.

There was a small token effort to include girls in the funnies -

Dennis the Menace had his female equivalent in

Minnie the Minx - but by and large these were male characters doing male things in environments that girls were just not going to be interested in. No dolls, no horse riding, no swimming, cooking or whatever the hell young girls did back then, It was probably (can’t remember now) considered uncouth of girls to read boys’ comics, which would often be mildly crude, and not the sort of thing an impressionable seven or eight-year-old girl would be expected to be reading, or that her parents would want her to be reading. In that way, I guess girls’ comics grew up, or helped girls grow up, faster than ours did. While we were still guffawing about the antics of

Ivor Lott and Tony Broke or

Odd Ball, they were learning about romance and mystery.

But that’s how it was, both in Ireland and in England: girls and boys were almost a species apart, and until those hormones kicked in neither wanted anything to do with the other. Boys played rough boys’ games, girls skipped rope and played shop or with dolls. There were some games both sexes could play, but by and large they were kept apart by a mutual sense of disinterest in the pursuits of the other. And so this reflected itself in comics too. Where girls might even enjoy school, boys generally did not, and this was played out in the panels of the comics we read. Boys liked violence, loud noises, disrespect to adults, bikes and cars and all the sort of things they more or less continue to like when they grow to be men. Girls were more select in their tastes, and comic publishers in general were not interested in having their writers create those sorts of comics, leaving the “funnies” more or less a male-dominated area, both in its characters and in its readership.

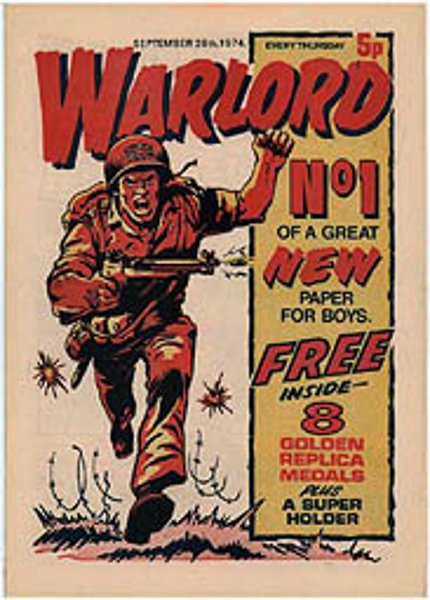

Later, of course, as I grew up such comics no longer interested me, and I moved on to the kind of thing teenagers read: war comics, football comics, adventure comics and the slowly-emerging science-fiction and later superhero comics. These tackled their subjects much more seriously, had a lot more dialogue, and much less of the sound effects and tomfoolery. These stories had to mean something, usually had to teach something, even if it was again a simple message such as Germans are bad (generally the message taught through the British publishing houses that put out such titles as

Warlord, Battle Picture Weekly and

War Picture Library) or any kid can become a soccer star if they work hard enough. The latter a laudable message, the former less so, but a message nonetheless. These comics, rather than the “funnies”, as we called them, would have been the first impetus for me to think about writing myself.

Later I moved on to the newly-released

2000 AD, where the writing was top-class and the stories multi-layered and intricate, many running over several, even dozens of issues, a clever ploy by the publisher to ensure you kept buying every issue, or prog, as they were called. And then of course there was

DC and

Marvel, opening up a whole new world of superheroes, adventure and the concepts of right and wrong. At this point comics really became more what are termed today as graphic novels. In the early “funnies”, nobody had to be drawn that well. Most of the characters were caricatures - big noses/ears, shocks of hair, pimples, buck teeth - and bore little resemblance to anyone I knew (I mean, what the hell breed of dog was Gnasher anyway, and why did he look so much like his owner? Or was that the other way around?) while others were so way out they just could exist nowhere other than in the pages of a comic:

Billy Whizz, with his elongated, lemon-shaped head,

Korky the Kat and the aforementioned

Creature Teacher.

But as we matured so did our tastes, and our tolerance for fantasy. We now wanted stories and characters we could identify with, even aspire to. War heroes. Space pilots. Footballers. Magicians. Superheroes. These people, while it could not be said in fairness that they prepared us for real life, did at least help us leave behind the zany madness of Bash Street, where every “slap-up meal” consisted of bangers and mash (sausages and mashed potato, to you Americans!) and cats walked around on two legs, or cowboys with unrealistic stubble ate cow pies. If you’re not British or Irish you won’t get these references, but don’t worry: this is just a freeform introduction, and we’ll be investigating all of these, as well as of course your own favourites, and looking at comics all over the world.

I of course was a child of the very late sixties (born 1963) and early seventies, so the comics I started on were a long way from being the first in the world. You can go back to the 1940s and 1950s for the popular pulp fiction comic books such as

Suspenseful Tales and

Amazing Stories, and further even, to the 1920s and 1930s* where comics began as newspaper strips. The history of comics goes back quite a way, and as I said earlier encompasses about a hundred years* of drawing, writing and development.

You know the deal by now I’m sure. In this journal I’ll be going right back to the very origins of comics, looking at how they developed over the last hundred* years or so, the differences between different countries and cultures, our favourite and least favourite characters, and how some of the comics we loved as kids grew out of the restrictions of the flat page and walked right onto the silver screen, or maybe the small one as comic characters translated to movies and television. We’ll also be looking, in time, at the growth and expansion, some might even say explosion of the graphic novel, where writing and drawing comic books has become not only an art but a true cultural phenomenon. We’ll see how the first crude line drawings gave way to full-colour illustrations of such beauty and complexity as to rival the greatest of the Old Masters (yeah not really), accompanied by writing so profound and deep that it can be read almost as a novel itself (really). We’ll be checking out the careers of some of the best - and lesser known - in the business, from artists and writers to the considered lowly letterers and inkers, the editors and the publishing houses, small and large, and how things have changed over time for comics.

I’m sure it will be no surprise to anyone to hear that we’ll be following a timeline, trying to parallel the development of comics on both sides of the Atlantic, as for once I don’t think (though I may be wrong, we’ll see) that in this area either America or the UK had the lion’s share, or that one followed the example of the other, but that the two markets grew - while in different stylistic directions of course - more or less at the same time.

So come with me now, back to the days of your childhood, or hell, dig into that comic collection you’ve been saving for a special time, and let’s go explore the history of comics.

* Oh hell no: in my initial research I've found the history goes MUCH further back than that!