Death to the Working Man: The Miners’ Strike of 1984/5 and the Fall of the Coal Industry

The Miners' Strike, March 6 1984 - March 3 1985

Timeline: 1984/1985

Era:

Death to the Working Man: The Miners’ Strike of 1984/5 and the Fall of the Coal Industry

The Miners' Strike, March 6 1984 - March 3 1985

Timeline: 1984/1985

Era: Twentieth century

Year: 1984 - 1985

Campaign: n/a

Conflict: Miners' strike

Country: England

Region: Nationwide

Combatants: The National Union of Miners (NUM) vs The National Coal Board (NCB), the British Government, the Metropolitan and South Yorkshire Police

Commander(s): (NUM) Arthur Scargill, Leader; (NCB) Ian McGregor, CEO, Leon Brittan, Home Secretary, Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister, Peter Wright, Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police

Reason: Protest against the planned nationalisation of the coal industry in Britain, with the ensuing closure of many pits and loss of jobs

Objective: Force a rethink of the government's position, retain all mines

Casualties (approx): 6 dead, 123 injured, 11,291 arrested of which 8,392 charged

Objective Achieved? No

Victor: British government

Legacy: In the end, a bad one. Thatcher nationalised the coal industry and eventually closed down all pits in Britain, and a way of life that had persisted for hundreds of years, a proud tradition was forever erased from British life.

All through history one truth has remained constant, and will continue to do so surely, unless or until we reach some unlikely Utopia, and that is that the working man and woman gets the short end of the stick. Time and again we've seen the little guy being beaten down by big industry, corporation, governments and other authority figures. And while it might be simplistic and trite to refer to the 1984/5 national Mining Strike as a David vs Goliath situation, in ways it does characterise the struggle of the ordinary working man against the implacable and uncaring monolith of government. The problem with that is the only place where David ever bests his huge and more powerful enemy is in the Bible; everywhere else, when the little guy takes on big business he generally tends to lose. Throw the adamantine champion of market forces, Margaret Thatcher, into the mix, and you have a recipe for disaster.

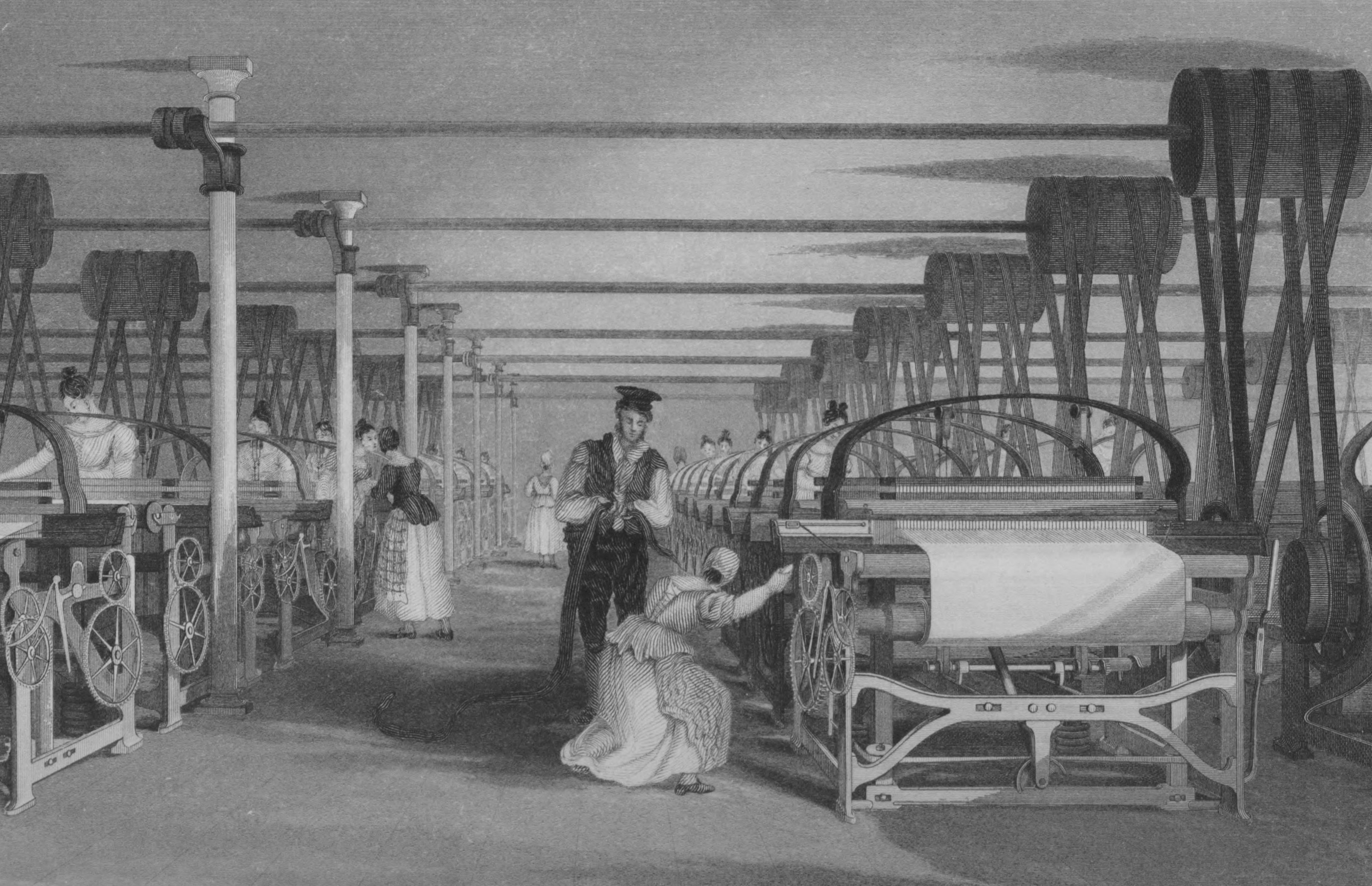

British political parties have never liked unions, especially when they're in power. Britain was built, during the heady days of the Industrial Revolution, on the backs of working men, women – and indeed children – who got paid little more than a slave wage, had no pension at the end of their many years of service, had no recourse to the law if they fell out with their employers or were treated badly by them, could be fired with little or no reason, or have their wages reduced, and had no health or safety benefit, no protection. So when they – as they invariably did, as safety practices were laughable in the early to late nineteenth century – had an accident at work, even a serious one that precluded them from working, and could be directly attributed to their employer, they were simply dismissed. Nobody looked after them, nobody helped them, nobody cared.

And this was exactly how the bosses liked it. Workers were two a penny (sometimes almost literally so) and easy to replace, and there were major profits to be made. The owners of steel or cotton mills had no time for the whining of a worker who had stupidly caught his arm in a machine due to there being no guard rail, or who had fallen into a hole and broken a leg because the area was inadequately lit, or who had died of tuberculosis or other diseases due to breathing in toxic chemicals in their factory. Who cared about them? These people were scum, and there were orders to fill! Get someone else in, and throw that cripple out of my factory.

Then came the union.

This was a disaster for employers. Suddenly they were supposed to, what, provide for the welfare of their workers? Pay them – what's that you say, I thought I misheard? A

decent wage? Oh now really! Next you'll be suggesting we look after them if they should injure themselves while working for us! What a singular idea, sir!

But these were the “outlandish” ideas the bosses of factories, mills, and other places of employment slowly and grudgingly had to learn to accept, because now the union was power. Every man or woman who worked for the boss had to be in the union, or they weren't allowed to work. And every union member had to do as the union said. And like it or not, the employer's business was his workers. If he had no workers he had no business. Unions introduced perhaps the most chilling word ever to reach the ears of a rich, impatient, unfeeling boss.

That word was strike.

For the first time, if conditions were bad, pay was low, or anything else was wrong, the union could bring out the men and women on strike. This meant they did no work, and more, marched outside the premises with placards announcing their grievances against the boss, causing often irreparable damage to his reputation, and hitting him where it hurt: in his wallet. Not only that, but once one crew went out on strike, it gave others ideas, and soon every factory and firm had a union, and could sue for better wages or working conditions, shorter hours, health benefits, safety procedures... in short, they could take their grievances to the management and if the management told them stuff it they could walk out. Management would then be forced to deal with the union representative(s) and hammer out a compromise so that their workers would return and they could get back to filling their orders.

Labour relations would never be the same again.

Of course, sometimes a strike could be called against the majority's wishes – if the union demanded it, the workers had to comply or risk being ostracised as “blacklegs” or “scabs”, a label that would stick to them for the rest of their working lives and ensure they would never work in any union-controlled environment again. The unions had become so powerful that it was seen as madness and folly to go against them. Governments of course hated them, as they saw themselves as being held to ransom; give us what we want or we go on strike, and people can walk to work, do their own operations, feed themselves, or whatever. The government in power had to cultivate a co-operative attitude towards the unions, but it was an uneasy truce at best, and easily broken, leading to strikes that could quite literally paralyse the country, and in some cases, bring down a government.

It had happened before, and in living memory too.

1969: End of the Summer of Love for Labour

1969: End of the Summer of Love for Labour

The first proper strike action taken by miners was in 1969, when working hours for the older, surface workers, which were supposed to have been reduced due to the men's age and lack of ability to work underground (resulting in lower wages) were left as they were and union representatives, including a young Arthur Scargill, who would later feature in the 1984 strike, and who is covered in a separate piece later, pushed for strike action. It only took forty-eight hours after the vote for strike action for every mine in Yorkshire to come out, followed by those in Kent, South Wales and Scotland, and coal production ground to a standstill.

As per usual though, cash is king and money triumphs over morals, as the miners were offered an increase in wages if they went back to work, though the plight of the older surface workers – which had been the catalyst for the strike in the first place – was left unresolved. Workers voted with their wallets, or for their wallets, and returned to the mines. However it was now clear that, no matter who was in government, whether their political ideologies lined up or not (Labour always having been associated with socialism and communism, not so much today of course) the miners and the unions would take them on if they felt either that they had a good chance of winning or if the cause was, in their view, just. They would prove this to be true again, less than three years later, when the balance of power shifted to the right.

1972

This time the cause of the strike was pretty simple: the miners were not happy with how much they were being paid. This was the first official strike by miners – 1969 having been an unofficial one – supported strongly by the NUM (National Union of Miners) and the TUC (Trades Union Congress), and the first since the General Strike of 1926. The mood was militant, involving flying pickets (see the entry on Arthur Scargill) and made the more serious by having the dubious honour of being the first strike in which a miner was killed. This was not, as you might think, due to police violence or scuffles on pickets – not technically anyway – but occurred when a lorry driver who was not affiliated with the NUM tried to deliver to one of the collieries under picket, mounted the pavement at speed to get past them as he left and ran over Freddie Matthews. The driver did not stop (I assume he was terrified that the miners would attack him, both for being a strike-breaker and for killing one of their own, though that's hardly an acceptable excuse for what was basically a hit-and-run, even if it was an accident) and the police had to stop him about a mile down the road. A crisis point had now been reached.

Things got violent as the NUM members attacked members of the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS), which mostly comprised foremen and supervisors, who had refused to strike and continued to work. The worst of these clashes took place at Saltley Gate in Birmingham, and came to be known as the Battle of Saltley Gate.

Standing at the Gates: Miner Differences

Standing at the Gates: Miner Differences

There was huge support for the miners, as the unions representing the railways agreed not to take any action that could be considered strike-breaking, including but not limited to driving trains that were to carry fuel, while all colliery workers stood down and the pits closed. Dock workers turned away or refused to unload ships carry coal destined for the power stations – some humanitarian exceptions were allowed, such as deliveries to hospitals, nursing homes, schools and so on – and the miners set about picketing the actual power stations themselves. This of course led to power outages as the electricity began to fail, and winter closed in.

One of the main plants to stay open was – although said to be Saltley Gate – Nachell Gas Works, where production had ramped up like nobody's business, and which, the strikers assumed (and probably correctly) if left open would lead to other works remaining open too, weakening their position, which of course depended on strangling the supply of coal to the nation and forcing the government to give in to their demands. A large force of police met them at the works on February 10 but could not hold them back, with reinforcements now from the engineering unions too, and they forced the plant to close. It was a huge victory for Arthur Scargill and his flying pickets, and a turning point in the strike. Nine days later the miners were offered a better deal, took it, and the strike was over.

Two major results of the strike were the Wilberforce Enquiry, which found that for the kind of dangerous, dirty and health-hazardous work miners carried out, they were very much underpaid, and in an attempt to ensure such events were better handled and responded to in the future, the government set up COBRA, which, though it sounds cool and CIA-like, merely stands for Cabinet Office Briefing Room (with an A added for, well, effect I guess: COBR doesn't sound as good, does it?) where the ministers would all gather and discuss whatever crisis they happened to be dealing with. The equivalent, I guess, of the Situation Room in the White House.

1974

Less than two years later, another Conservative government tried to close the mines and paid the ultimate price of electoral defeat. It had begun with a round of pay freezes to combat high inflation, and ended in the fall of Edward Heath's government in 1974. Like the strike of 1984/5 this was a case of two polar opposites meeting, but with a different result. In 1974 the combatants were basically the British Communist Party and the Conservative Party, so essentially capitalism versus communism. The principle proponent of the latter half of that struggle was a man called Mick Mc Gahey.

Mick Mc Gahey (1925 – 1999)

Mick Mc Gahey (1925 – 1999)

Like father, like son. Mick was still in nappies, barely a year old when his father, founder of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) took part in the General Strike of 1926, which fell flat, despite the tacit support of no less a personage than the king himself, who suggested

“Try living on their wages before you start judging them”, mostly because of fears of the rise of communism in the wake of the end of World War I. This led to the government of the time (yet another Conservative one) enforcing the Emergency Powers Act, passed only six years previously in 1920, which allowed the sovereign to declare a state of emergency if required, and rallying support against the General Strike by pointing out that it was motivated and orchestrated by communists (which was, at least in part, true). This turned many ordinary people, who would have likely otherwise been on the side of the miners, away from their cause. In response to this claim, the national newspaper of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), the

British Worker, hit back:

"We are not making war on the people. We are anxious that the ordinary members of the public shall not be penalized for the unpatriotic conduct of the mine owners and the government".

Support among workers for the strike was overwhelming, and the country was brought to a standstill on May 4 when the Transport Workers Unions, the National Transport Workers Federation and the National Union of Railwaymen joined the strike. Under the terms of the Emergency Powers Act, the government set up a sort of militia to ensure supplies kept moving, though loyalties within the Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS) were certainly divided, as evidenced by this constable's comment:

"It was not difficult to understand the strikers' attitude toward us. After a few days I found my sympathy with them rather than with the employers. For one thing, I had never realized the appalling poverty which existed. If I had been aware of all the facts, I should not have joined up as a special constable".

The nascent Fascist movement in Britain also took the initiative to combat the strikers (is there anything fascists enjoy more than beating the s

hit out of reds?) but were not allowed to join the OMS because of their overt political agenda. They therefore formed their own quasi-military unit, Q Division. As the Army got involved, things could have got ugly, and there were some incidents, but generally speaking compromises were worked out with the union and by May 12 most of the men were back at work. Miners, more militant than other workers – and who had gone out on strike first, the rest coming out in sympathy with them – remained defiant for some months afterwards, but eventually the pressure of no money in their pockets and the exigency of putting food on the table forced them back to work.

Sadly, they ended up worse off than they were before they began the strike, having to accept lower wages, longer working hours and unwittingly contributing both to the demise of British coal as an industry and to two further strikes. The General Strike of 1926 also gave rise to the Trade Disputes and Trade Agreements Act of 1927, which prohibited mass picketing, general strikes and sympathy strikes. You would have to say that the 1926 strike achieved precisely nothing, but this did not stop our man Mick from kicking off another one fifty years later.

Having followed in his father's footsteps and joined both the CPGB and the newly-formed National Union of Miners (NUM) – well, formed in 1945, so twenty years after the General Strike – McGahey rose in the ranks of both organisations, becoming the Vice-President of the NUM in 1972 and elected to the Executive of the CPGB the previous year. This put him in a position to really make waves on behalf of his members, and he did not spurn the opportunity. When Heath passed the Three Day Work Order in 1973, his hackles were raised. The Three Day Work Order required consumption of electricity (of which coal was almost the only power source) to be limited to three days a week. TV stations had to shut down at 10:30 each evening, pubs were closed due to the lack of electricity to power them, and working hours were reduced.

Miners rejected a 16.5% pay rise offer the following January, and McGahey called for strike action. On hearing the army might be called in, he sneered “You can't dig coal with bayonets”, and suggested the army should disobey orders if they received them, join in solidarity with their working class brothers. Despite being a militant communist – and presumably therefore a supporter of the Labour government – McGahey's call angered the MPs so much that over a hundred of them signed a resolution condemning him. Battle lines were clearly being drawn.

The strike began on February 5 and Heath called a General Election, using the striking miners as an example of the bolshevism that threatened to take over Britain, and the slogan

Who governs Britain? It turned out to be the wrong tack to take, and Heath and his government had wrongly assessed the mood of the people; although his Conservative government was not defeated, it did not win either, and in what is known as a “hung parliament” - where there's basically a stalemate; neither side has achieved enough seats to form a government – Labour gained most and eventually formed the new government, returning Harold Wilson to power after a mere four-year gap in Labour governments.

Aware of the part the miners had played in his return to power, Wilson immediately authorised a pay rise of 35% for the miners, with a further 35% awarded the next year.

There would, however, be no happy ending for the miners of Great Britain. If one person could be said to have sounded the death knell of mining in the UK - hell, she practically danced on its grave! - it would be the enemy of the working man, the hero of the rich, and the worshipper at the altar of market forces.

She would be Britain's first ever female Prime Minister.

(Concludes next week)