All right then, back to our timeline. Let’s check out how things progressed after balloons were the only real method of aviation in the world. In other words, let’s explore the history of powered flight, which begins, well, further back than you might think.

Timeline: 15th - 16th century

Timeline: 15th - 16th century

If there’s one thing guaranteed to bring a chuckle when you talk of early attempts at flight, it’s the often catastrophic failures. I mean, who hasn’t pissed themselves at that old silent movie of the bicycle under massive, massive wings that goes forward a few paces and then the wings collapse on it and it falls over? Well that was later, but consider the plight of one John Baptist Danti, who decided to do a kind of Icarus in reverse, way back at the end of the fifteenth century.

"One day when many distinguished people had come to Perugia for the

wedding ceremony of Paolo Begliono; and were holding a festival in the

main street; Danti suddenly jumped from a nearby tower using a rowing

device with wings, which he had constructed in proportion to the weight of

his body. He flew successfully over the market place, producing a fair

amount of noise, and was watched by a large crowd. But when he had flown

a distance of barely three hundred paces, an iron component on the left

hand wing broke, so that he fell onto the roof of the Church of Maria

delle Virgine, and was seriously injured."

You can’t help but say it, can you?

No doubt the local Inquisition would say the hand of God had intervened and stopped poor old Danti from flouting the laws of nature, consorting with the Devil and so on. Nothing like a good old-fashioned impalement to put a stop to that nonsense! The dawning of the new century did nothing to dampen the fervour, or indeed good sense or logic, of those who wished to fly, as another Italian, John Damian, decided the best way to overtake an ambassador on his way to France, for some reason, after his installation as Abbot in Edinburgh was to fly, and never mind the trifling detail that man had not yet managed to do this successfully. Perhaps he would be the first to do so.

He would not.

Completely failing to achieve any height, he plummeted straight down from the battlements of Stirling Castle, smashed into the ground but luckily only sustained minor injuries. He blamed his failure not on his lack of aeronautical knowledge or experience, but on - wait for it - the fact the he had used hen’s feathers in his wings. Well of course! The hen feathers, being from a barnyard bird rather than one that flew through the sky, had been attracted back down to the ground, thwarting his attempt to break the surly bonds of earth and punch the face of God. Whether or not any hens were hurt in the attempt is not recorded, but our John certainly was, breaking his thighbone, though he may consider himself lucky that’s all he broke. Meanwhile, the ambassador presumably proceeded on his way, boringly using the banal transportation method every other sane person of the time was using, a ship.

1540 saw yet another John (alright, Joao, but I think it’s a Spanish version of the name), this time in Portugal, perhaps the first attempt at flight in that country? Obviously taking the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, the first man I believe in the world to truly study and understand - if incorrectly - the principles of flight, though he never built any machines and certainly never flew - as his yardstick, Joao Torto built a kind of winged structure which he strapped to his back in order to enable him to make his flight. He then announced his intention:

"I proclaim to all the inhabitants of this city that before this month comes to an end, a very great miracle will be seen, in the form of a man who will fly with magic wings from the clock tower of the cathedral towards Matthew’s Fields.”

Seems his flight actually worked - for about a few seconds, until the hood he had seen fit to wear (painted with an eagle’s beak) slipped and obscured his vision. With no way to see where he was going, and unable to move his hands to the hood as they were strapped into the wings, down he went, crashing into the roofs below. Luckily for him, he was not seriously injured. This did not stop another cleric, a monk called Kasper Mohr (should have had Mohr sense, sorry sorry) from attempting something similar, but in his case his superiors stopped him in time, just as he was about to jump from the roof of the monastery. “Oh no you fu

cking don’t, son!” they snapped, dragging him back. “Consider the birds of the air, and leave the flying to them. Haven’t you manuscripts to illuminate or something?”

You couldn’t even say attempts at flight were in their infancy in the sixteenth century, more a sort of embryonic stage, where people who should have known better, but didn’t, attempted to do things they couldn’t possibly hope to achieve, with virtually no working knowledge of the mechanics that were supposed to launch them triumphantly into the sky, but more often than not just caused them to plummet painfully to the earth. Some successful flights were claimed, but there’s no backup for any of these, so we can assume either they were exaggerating or outright lying, probably knowing their accounts could not be disproven.

I mean, you have the French locksmith (huh?) Besnier, who claimed he had completed several successful flights with his stick-on bird wings, but when he sold these to another eager aviator the guy died on his first attempt. Who corroborates Besnier’s account? What proof was offered the luckless and presumably gullible showman who bought the wings from him? And what of Allard, the tightrope walker who promised King Louis XIV he would fly, but instead dove straight down and came a cropper in front of the Sun King? This kind of nonsense, you’ll be amused to hear, continues on into the next century.

Timeline: 17th century

It’s an odd dichotomy to me that the larger percentage of men (always men, of course) who attempted to fly were men of the cloth; considering how the Church frowned on any such activity, you would think its adherents and officers would have kept away from such blasphemy. But again we have a cleric, this time a friar, possibly thumbing his nose at God, certainly at the authorities of the Church. What’s the difference between a friar and a monk, you ask? Apparently monks tended to stay in the country, and on desolate islands, sort of thing, whereas your friar was a more urban sort of guy, hanging out in towns and cities. Anyway, this one, Friar Cyprian, is supposed to have not only tried but succeeded in flying with wings strapped to his body, though no proof is of course offered and there were no witnesses. But even so, the Church weren’t standing for that, oh no.

The Bishop of Nyitra is recorded, probably, as saying “Let’s see if that fu

cker can fly without his wing contraption, the heretic!” and sent his people to torch them. It seems the good friar got off being torched himself, but that may have been more to do with the political structure in Hungary than any leniency on the part of the Church.

Very interestingly, just as the history of ballooning involved Italians heavily, it’s an Italian we look back to as the first inventor of what could be called any sort of an aeroplane, and no, I don’t mean Leonardo. Though he designed models, he never built anything that I can see, and certainly never flew, so while in some ways he could be considered the father - or at least, great-grandfather - of flight, he doesn’t figure in the actual history of aviation. The first man to successfully transport a living creature in a powered vehicle, other than a balloon (which is only powered, in the end, by the wind, and not really capable of being steered or directed) was this guy. Though to be fair, it wasn’t a man he managed to fly. Nor was it really a powered flight.

Tito Livio Burattini (1617 - 1681)

Tito Livio Burattini (1617 - 1681)

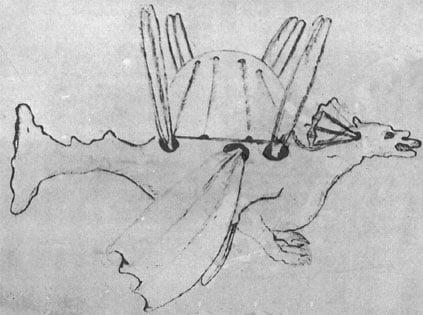

A nobleman who was born in Italy but spent most of his working life in Poland and Lithuania, and when called to the court of the Polish king in 1641, he built a four-winged glider, which is said to have lifted a cat (why is it always a cat? Maybe because they’re smaller and less excitable than dogs?) into the air, and presumably returned it to the ground safely. He was then given permission to build a full-size model, which would carry three men and would, he said, traverse the distance from Warsaw to Constantinople in just twelve hours. All that remains of it though is this sketch of a “flying dragon”, which he drew in his treatise entitled

Il volare non e impossibile, which even I can translate.

A man given the perhaps grandiose title of the Father of Aeronautics was again Italian, a priest living in Lombardy, who sketched out and designed what was called a vacuum airship. That’s him below.

Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631 - 1687)

Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631 - 1687)

Although he is known also for the development of a reading system for blind people, known today as braille, de Terzi was the first to propose the idea of a vacuum airship, and his drawings make it clear that if anything looked like what it sounds, this did exactly what it said on the tin. Or would have, had it ever been built. And flown. Remaining though on the drawing board, you can see below how it literally looks like some sort of sailing ship making its way through the sky. It has the gondola, the mast, even the sail, but it operates (or would, or does in theory) on a wholly different principle to both balloons and later airships. Whereas an airship or dirigible is essentially a big balloon, with air - either hydrogen or helium - pumped into it to inflate it and keep it afloat, de Terzi’s idea worked on a principle of air being removed. How? Glad you asked.

See those big balloons there either side of the sail? Yeah that’s what I thought too, but they’re not balloons. They are in fact large copper spheres, from which the air has been - in theory - pumped out, leaving a vacuum inside. As this vacuum is then lighter than the air, it provides lift, and de Terzi calculated that the airship would transport six people. Without an engine of any kind, I suppose really it has to be considered more a high-tech (for the time) balloon, with no real way of steering against the wind, but because the kind of copper required for the spheres was not yet available - and has yet to be - the airship could not be built.

There was another reason though, a darker one. De Terzi, certainly a man ahead of his time, and coming from a country split into constantly warring city-states, knew the potential such a device had to be misused by the military as a weapon, as he wrote

“God will never allow that such a machine be built…because everybody realises that no city would be safe from raids…iron weights, fireballs and bombs could be hurled from a great height". Oh, surely not, Signor de Terzi!

An odd postscript to this is that today, four hundred years later, scientists, engineers and aviation enthusiasts are still grappling with the idea of a vacuum airship, and despite better materials being available then ever were to the Italian seventeenth-century Jesuit, the probability that such a device will ever be made, much less fly, seem as remote now as they were back then. Some things, I guess, just are not meant to be, and the passage of time can make very little difference.

Pinning down an actual aviation pioneer in the seventeenth century though seems hard, if not impossible. Like many great men of the time, people like Robert Hooke and Giovanni Borelli were interested in the idea of flight, but this seems to have been more a casual fancy, a diversion from their many other scientific pursuits, and so it is not really until the eighteenth century that we find people actually grappling with the problem in a serious way, devoting some energy, effort and intelligence to its solution.

Some guy called Hezarfen Celebi was supposed to have flown from a tower in Galatia to Scutari, a distance of several kilometres, but surely if he had done, this miracle would have been in all the pamphlets and woodcuts, or cried by the town crier in every town, or whatever way they communicated news back then? 1742 saw the Marquis of Bacqueville give it a go with the tried-and-not-trusted wings stuck to the body deal, but he had the misfortune to jump off a roof which overlooked a river, which should have been a relatively soft landing for him in the event/certainty of failure. Just his bad luck then that a barge was passing as he leaped, and he crashed right onto its deck, smashing both his legs in the process. Ouch! Shouldn't have touched that one with a ten-foot... okay, okay.

Bartolomeu de Gusmão (1685 -1724)

Bartolomeu de Gusmão (1685 -1724)

Although he was more concerned with airships, and we’ve already done balloons and indeed dirigibles, I think airships merit being included in powered flight, as they certainly were directable and had engines and navigational equipment. You didn’t just climb into an airship and trust to the winds: the pilot could go against the prevailing currents of the air, so in effect I think you could say that airships were the true forerunners of aircraft, and this guy was one of the first to really take on the idea of designing and flying one.

You wouldn’t really expect a priest to be thinking about man flying, would you? Surely more the type of man who would have said if God had meant us to fly he would have given us wings. But be that as it may, de Gusmão was a Portuguese priest born in Brazil, a Jesuit who in 1709 secured the patronage of the King of Portugal to design and test an airship, which was of course far different to what we know as one today. Like most of the inventors, scientists, thinkers and designers from about the sixteenth century to the eighteenth, de Gusmão envisioned his airship as being built around a kind of small boat, creating a sort of cradle in which the pilot would sit, with a large sail pulled over it like a massive parachute. Air would be pumped through bellows into hollow tubes with magnets acting as - you know what? I have no idea how this was supposed to fly, but here’s a drawing of what it was supposed to look like.

For whatever reason, the public demonstration of his airship, which he christened

Passarolla, never took place. Nevertheless he became a favourite with the king, who fired him out of a cannon, sorry, appointed him a canon and later made him the royal Chaplain. He also granted him an early version of a patent, though the penalties for copying his machine seem to have been a bit more stringent than they would today!

“Agreeable to the advice of my council, I order the pain of death against

the transgressor, And, in order to encourage the suppliant to apply

himself with zeal towards improving the machine which is capable of

producing the effects mentioned by him, I also grant unto him the first

vacancy in my College of Barcelona, with the annual pension of 600 000 reis

during his life."

Right. So if you f

uck with my boy’s patent, you’re literally going to lose your head. Talk about a cut-throat business practice! Sorry. Anyway de Gusmão also had some odd idea about making a sailing ship of the air, using a triangular gas-filled pyramid, but he died without making progress of any sort on this design. Of course, you could always rely on the Church to cry heresy when any such experiments were undertaken, and there is - uncorroborated - evidence that the Portuguese Inquisition (nobody expects the Portuguese Inquisition! Literally, nobody. Spanish, yes. Italian, maybe. Portuguese? Never ‘eard of it, mate) came after him and that he had to flee to Spain (not in his airship of course). Whatever the truth of that, he died soon afterwards, in 1724, fifteen years after his non-demonstration and a few months short of his fortieth birthday. They named an airport in Brazil after him, but it got renamed in 1941, so they named another one after him, and so it stands today.

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688 - 1722)

Another who drew but did not create a flying machine, Swedenborg was happy to let future inventors sort out the nuts and bolts and get the thing flying. He wrote

"It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come some one might know how better to utilize our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest. Yet there are sufficient proofs and examples from nature that such flights can take place without danger, although when the first trials are made you may have to pay for the experience, and not mind an arm or leg."

One of his quotes - not actually his but one he made use of, presages the clever clogs in the 19th century who claimed that “everything that can be invented has been invented” when he pleaded for a modicum of hope and restraint of hubris:

"The art of flying is hardly yet born. It will be perfected and some day people will fly up to the moon. Do we pretend to have discovered everything, or to have brought our knowledge to a point where nothing can be added to it? Oh, for mercy's sake, let us agree that there is still something left for the ages to come!"

Swedenborg clearly had not the first clue how to solve the problem of flight, but had sketched out what he thought might be a neat idea, with a man seated in a sort of basket, where the pilot was supposed to sit, and operate large paddles attached to the one wing, which would move the machine through the air. Like many designs before and after it, Swedenborg’s flying machine seems to have taken the idea of the mechanics of bird flight as its yardstick, which is not surprising. Birds do move through the air by beating their wings, but it would later be conclusively proven that this could not be emulated by humans, and that the only way to fly would be to use the air currents and more or less glide, until the engine was invented.