Back we go to Robert Emmet then. Unlike some of his contemporaries a few years earlier, he is said not to have relied upon French assistance for the rising, but it all went to hell in a handbasket anyway. Honestly, if it wasn’t so serious it would be hilarious, and one thing it certainly was, was typically Irish.

The rising - which hardly deserves the name, lasting less than a day - was beset by problems from the very start. To be fair to Emmet, he and his people do seem to have learned from 1798, and in addition to the standard pikes (some of which could fold up to be concealed under cloaks) he had grenades, rockets and exploding wooden beams. He had no artillery, of course, but at least, weapons-wise, he was a little better prepared than his brother’s crew five years previous. Unfortunately, everything that could go wrong, did.

An accidental explosion at one of his concealed arms depots led to the date of the rising being brought forward before the caches could be discovered, and so on July 23 1803 the rising was to begin. Quite cleverly, or at least astutely, Emmet had proclaimed that the coming rising was not a sectarian one:

"We are not against property – we war against no religious sect – we war not against past opinions or prejudices – we war against English dominion."

In this he hoped to show this was not a case of Catholics rising against and fighting Protestants, but Irishmen resisting the occupying English overlords. He gave assurances that there would be no revenge reprisals against loyalists, no outrages or attacks. It was a canny thing to say, and should have helped secure if not support at least no resistance from sides which up to now had always been opposed and which lived in mutual distrust and fear of each other. In effect, what he was saying was "look lads, all that burning down houses, killing Protestants, atrocities - it's all

so eighteenth century. This is a new age, and we don't hold with that kind of stuff. If you're not with us, that's cool, that's cool. Just don't be against us, and there'll be no trouble. You want to join us, magic, very welcome. Just don't get in our way. Leave us alone and we'll leave you alone, deal?"

Fine words, and fine sentiments. Probably might have even worked. But again, the twin spectres of bad planning and the demon drink scuppered any chance Emmet’s rising had of being successful.

A large contingent of men, led by a former leader of the 1798 rising, Michael Quigly, arrived at Emmet’s weapons depots with what has variously been reported as hundreds or even thousands of men, eager to take up arms and fight for their country. The problem was that Emmet had not counted on such a large number turning up, and he hadn’t nearly enough weapons to supply them all. Shrugging, disgruntled and probably disparaging his lack of quartermaster skills, the Kildare men turned and headed home. Later that evening they would put into effect a half-hearted attempt at supporting the rising on their own, but this would flounder on the news that Dublin had failed to come through, and they quickly surrendered.

The plan, reasonably clever, had been to take Dublin Castle, the seat of power of the British government in Ireland. Being in the heart of the capital, this was only lightly defended, and Emmet planned to take it by stealth, using fine carriages to present the illusion of gentlemen on their way to a meeting to gain entry. The carriages though never arrived, due to a dispute between the commander and the local garrison, in which a soldier was shot. With no way into the Castle now, and a mere eighty men when he should have had about two thousand, Emmet now learned that his rockets and grenades were useless - some mix-up with the fuses, technical bods, you know how it is - and thought it best to try to call things off.

Unfortunately by now the thing had a life of its own, given impetus by the sight of his men completely pissed and reeling through the streets, firing at anything that moved, or indeed didn’t. Lamp posts were shot at, and we all know what a threat to Irish independence

they were! Trying to make the best of what was rapidly becoming the least impressive rising in the less than impressive history of Ireland’s attempts to break her chains, Emmet drew his sword, turned to his - by now almost completely drunk - men and shouted “Now is your time for liberty!” He might as well have shouted “Time, gentlemen, please!” for all the notice they took of him.

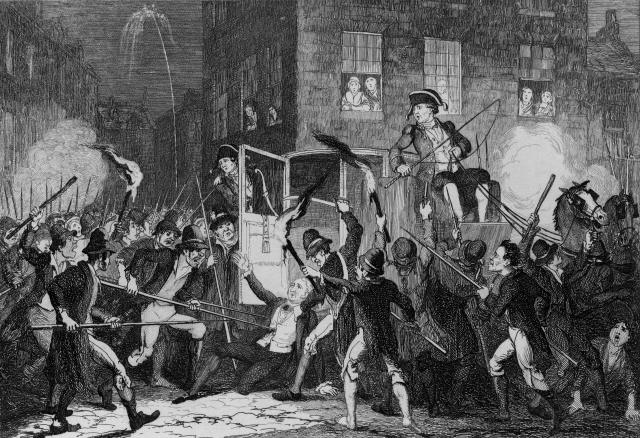

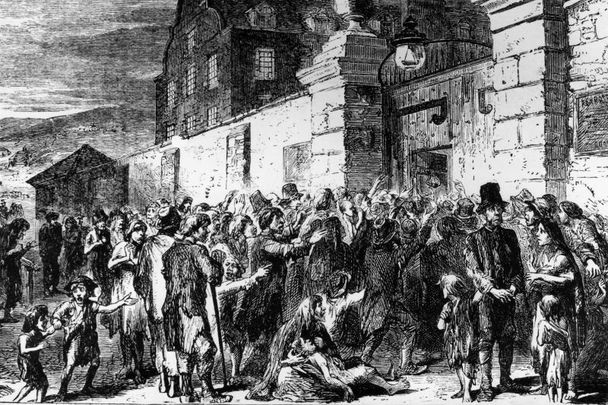

To darken the comedy a little, and bring things back to reality, let’s not forget that people did die in this truly ineffectual attempt at rebellion, which you have to imagine might only have succeeded due to the British being too helpless with laughter at the incompetence of the drunken Catholics to do anything. The Lord Chief Justice, Arthur Wolfe, Viscount Kilwarden, had the bad luck to ride down the street as the intoxicated Irishmen rampaged through Dublin, looking for a target. He was dragged from his carriage and hacked to death, while a single soldier was also pulled off his horse and met a similar end. Drunken soldiers then tried to force passers-by at Ballsbridge to fight for their country, but everyone ignored them.

By midnight, the military had finally got their sh

it together and hauled themselves out onto the street, where the rebels were easily dispersed, probably heading for any late-night drinking establishment that would let them in. Dejected, Emmet returned home to a brow-beating from his housekeeper for his failure and for abandoning his men (not that you could blame him really. It had all gone spectacularly tits-up).

In Antrim, hotbed of resistance in 1797/1798 and scene of the “Dragooning of Ulster”, nobody gave a s

hit. It was, in the end, way way too soon. The lessons of 1798 had been learned and were still raw wounds; nobody expected a rising to succeed, and nobody cared. One of the organisers of the attempted northern resistance, Thomas Russel, saw the grand total of three people turn out to hear him speak, and one opined that being subservient to the French would be as bad as being under the English boot. Nowhere in the country, with the small exception of some lacklustre action, as already mentioned, in Kildare, did the nationalist fervour catch. People were, in general, probably tired or risings that went nowhere, and also fearful of the dreadful reprisals for which the British had become infamous. You’re all right, they said: we’re grand thanks. In that fatalistic attitude typical of the Irish, they probably said "English occupation? Ah, sure, it will do."

Perhaps strangely (certainly strange to me), given that the rising had failed so utterly and so comically, Emmet still seemed to think that the French would be interested, and sent one of his commanders off to see if Napoleon fancied popping over and saving them from the English? It’s recorded that the emperor’s laughter could be heard as far as… well, no, it isn’t, but suffice to say Napoleon had enough trouble on his hands without taking on Ireland too. Had the Irish managed to take Ireland for him, defeat the English and give him a base he could use, well, there could be merit in that. But send an invasion force into a country still completely controlled by his enemies? Step into the lion’s den naked and weaponless?

Sacre bleu! Formidable! Or something.

Emmet was, of course, quickly captured, though he did himself no favours by switching his hiding place in order to get his leg over, visiting his girlfriend, Sarah Curran. Our old friend Leonard McNally, (remember him? Renowned traitor who helped do for the 1798 rising?) got involved in the trial and sealed the young leader’s fate. Sentenced to hang, Emmet made his last speech from the dock, one that, despite the almost bumbling ineptitude of his attempted rising, has gone down in Irish republican history.

"Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice or ignorance, asperse them. Let them and me rest in obscurity and peace, and my tomb remain un-inscribed, and my memory in oblivion, until other times and other men can do justice to my character. When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and not till then, let my epitaph be written. I have done."

And so ended the second major attempt at an uprising in Ireland. Well, not quite. I mean, you couldn’t call this a rising could you? It achieved nothing - other than the, no doubt unintended and certainly impossible to capitalise upon, death of the Lord Chief Justice (who had, paradoxically, been instrumental in saving the life of Wolfe Tone after the 1798 rebellion) - and was if anything further evidence, if any were needed, of the lack of organisation, commitment and discipline of the Irish Catholics, and even later champion of Catholic emancipation, Daniel O’Connell, denounced Emmet as “an instigator of bloodshed, undeserving of any compassion.” Padraig Pearse, calling Ireland to arms over a hundred years later in the final Rising, would have a different take. He would describe Emmet’s paltry rising as being “not a failure, but a triumph for that deathless thing we call Irish nationality.” Right.

Really oddly, the news of the rising penetrated as far away as New South Wales, where the exiled Irish heard about it a year after it had failed (though were probably unaware of the result) and tried to sail home to join up and fight for the country of their birth. Needless to say, they never made it out of Australia.

Dublin Castle was quick to hush the whole incident up. After all, they had had no idea at all of the plot being hatched in their back garden, so to speak, and had the carriages actually turned up as planned, the centre of British power in Ireland could, theoretically, have been taken. Eighty men (some possible sober) could easily hold such a fortified building (it is a castle, after all) so maybe they realised, red-faced, not only how close they had come to being actually overrun but also how easy it had been for the scheme to unfold without their knowledge or any intelligence of it whatever making it back to them. You kind of have to wonder, though, what happened to the network of traitors and spies spoken of in the chapter on the 1798 rebellion? This was only five years later, and as we’ve seen, McNally at least was still alive and squealing. How is it that this so-called network was unable to infiltrate Emmet’s United Irishmen and get word back to the Brits? Maybe Emmet, aware of or at least suspicious of the spies, made sure none of them got near him. I suppose we have to remember that many of these spies’ identities were only uncovered after the rising.

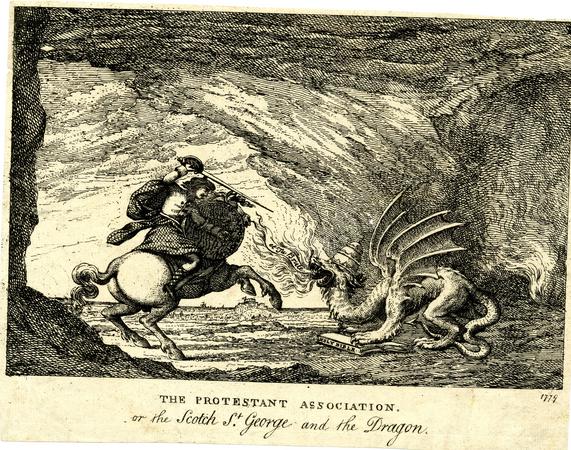

Even so, it was a catastrophic failure of intelligence on behalf of the English. I mean, imagine for instance a bunch of ISIS terrorists discussing taking the White House or the Capitol Building while based in an apartment block just off Pennsylvania Avenue. Not likely, right? And it should not have been likely here either, which led impetus to the British government to cover up the whole thing and hope it went away. It also gave them licence, however, to turn the spotlight back on the “unruly Catholics”, ignoring the fact of course that Emmet was a Protestant, as was Russell, and Jemmy Hope, another organiser in the north, was a Presbyterian.

I suppose you can at least say that Emmet’s heart was in the right place, and luckily for him, remained so. Although said to have been sentenced to death by hanging, drawing and quartering, any account I can turn up speaks of his being hanged and then beheaded, which means then that he avoided that most humiliating, terrifying and agonising of deaths traditionally reserved by the Crown for traitors, the ultimate deterrent, and also the ultimate ugly spectator draw. Who wants to watch a man hang when you can see him go through so much more? Perhaps by now the meaning of hanging, drawing and quartering had taken on a different meaning, perhaps the accounts I read were wrong, or perhaps the method of his death was commuted at the last, maybe in fear of unnecessarily stoking new hatreds among the Catholics. Anyway, it seems Robert Emmet was buried in an unmarked grave, until some years later when his remains were spirited to the family plot.

Personal Thoughts on Robert Emmet

Look, I’m not going to denigrate a patriot and an Irish hero - I even spoke to one of his descendants on another forum - but let’s be brutally honest: we’re dealing with a well-intentioned gobsh

ite here, aren’t we? Someone whose heart may have been in the fight but whose brain certainly could not have been. Firstly, why did he have to organise the so-called rising for when he did? I get he was pushed by the explosion at the armoury but even so, why did it have to be 1803, a mere five years after the Irish had been thrashed into submission with very little effort on behalf of the British? How could he have believed the country was again spoiling for a fight (without copious amounts of alcohol)? How could be not have understood that those who died in 1798 did so more or less in vain; that they achieved nothing at the time and failed utterly to rouse the country into rebellion, the only real bastion of the rising being Wexford? Why did he think the time was now? Why did he go looking for help from the French, and then, finding his requests turned down, go ahead anyway?

Even allowing for the fact that, against all the signs, he decided to proceed, how did he so badly miscalculate the ratio of guns to men? Could he really have interested that many more people than he had expected, and so had no weapons for them? And if he did, how could he not see that going ahead with the plan, left with less than a hundred of the two thousand men he had expected, was suicide and pointless? Even allowing all that, why couldn’t he keep his men - the few he had - out of the fu

cking pub? Everyone knows the worst place you can bring an Irishman is the local, and don’t expect to get any work out of him if he finds his way in there. Even given all of that, finding his men virtually drunk off their asses, why did he not call the whole damn thing off? But no. He had to go ahead didn’t he, making his crazy, all but suicidal and certainly symbolic gesture, and he paid for it with his life.

What has remained of Robert Emmet is a legend, built upon by successive attempts by Irish leaders to throw off the chains of oppression, and pointed to as a perfect example of the ultimate sacrifice, when in my opinion what it should be pointed to as a perfect example of is ho0w not to start an uprising! But Ireland loves her tragic heroes, and our history, and even our legend, is hardly replete with victories against our enemies, so we take refuge in the “nobility of sacrifice” and the “struggle for independence”, and so Emmet has become a folk hero, perhaps undeservedly. It’s sort of odd that he sounds like someone who was being used as a pawn, but this doesn’t seem to be the case. Napoleon could not have given

le merde single, the other leaders of the United Irishmen desperately advised him to call off the rising that morning but he would have none of it. So nobody seems to have been pulling his strings, leading him into a hopeless act of pointless rebellion. He walked into the fire himself, and burned in it.

His ineptitude and naivete has not stopped him becoming a hero though of course. Shelley was one of his biggest supporters, and one of the ones who helped create the myth that today surrounds him, and there are statues of him in Dublin, Washington and San Francisco. He has been depicted in story, song, on stage and screen, and has towns, counties, schools and parks named after him. He’s of course gone down in Irish history as one of the men whose sacrifice and refusal to bow down (or lay proper plans) led eventually to the freedom of Ireland, and I wouldn’t dream of trying to take that from him. At least he gave it a go, which in his place I can’t say I would have done.

There’s an Irish saying: God loves a trier, and Emmet certainly was one of those. Unfortunately, trying by itself isn’t enough. You also need to have a strategy, and in fairness he had, but he didn’t seem then to have any sort of contingency plan for what to do if one part of his - at the time - relatively well-thought-out plan fell apart. Essentially, it was like an engine which, no matter how well-made it may be, fails as soon as one part stops working. Section by section and module by module his plan began to fall apart, but rather than take note of that and try to readjust and adapt his strategy, he continued on with a bastardised version of the original plan, and so he was doomed to fail.

Ironically, though it would take another century and more before Ireland finally was free, the long-awaited and prayed for emancipation of Catholics was less than a quarter of a century down the road, and would be achieved, in the main, without the need to resort to risings, rebellions or violent struggle of any kind.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode