How the West Was Lost: Those Who Tried and Failed to Save It

How the West Was Lost: Those Who Tried and Failed to Save It

I certainly don’t have to explain to any of you, I’m sure, how badly treated the Red Man was by ourselves as the settlers moved West, and how their lands were taken, promises to them broken like bottles made out of papier mache, how they were cheated, lied to, confused, derided, murdered and raped, and all but made extinct as a race, all in the name of white expansionism. As a white man myself, though I wasn’t born for another century and even then was many thousands of miles from the scene of such savagery and betrayal, I nevertheless consider myself to bear a small part of the shame this sin stains, or should stain, every one of my race, and so I don’t point the finger and say “they did it” while smugly looking down from on high, but try, in so far as I can, to use the collective “we” and accept my part of the blame.

As a nation historically oppressed by others, and as one torn apart by differences both political and religious, I should be able to say I know what it’s like to be on the receiving end, but the truth is I don’t. I’m the equivalent of a man living, during the time of the West, in say Canada or New York, well removed from the carnage and the massacres, in no danger. While my people (Catholics) were being killed and driven out of Northern Ireland by the Protestants, I was safely in the Republic, where the population was overwhelmingly Catholic, and so never faced any kind of oppression for my religion, never mind that I don’t even believe. On the streets of Londonderry or Belfast or Armagh, pleading not being a practicing Catholic was no excuse and offered no escape; to Protestants (well, to the loyalist paramilitaries and their supporters) if you were baptised as a Catholic, or “Papist”, then that was what you were.

Naturally, this worked in reverse too. A Protestant caught in a Republican area, or picked up by the IRA, would not get out of it by saying he (or she) was non-religious. To each side the other was the enemy, and it didn’t matter if you were a mother of five or a old man, a schoolchild or a priest; there were only two sides, and if you weren’t with them, you were against them. Not to mention that if you somehow did escape your fate by declaring against your own side, or purporting to be outside of the conflict, the chances you would be seen as a traitor by your own side and punished by them were not inconceivable. Again, on both sides, you were either with them, or us, or against them, or us. No middle ground.

But if anything positive can be said about the sectarian conflict between Catholic and Protestant that raged for over thirty years over the border (and it really can’t), it can at least be admitted that there was a kind of brutal honesty there. Loyalist paramilitaries did not trick you into believing they were your friends, Republican punishment parties never pretended they would be all right with you living in their area. You were the enemy, you knew you were the enemy, they knew you were the enemy, and everyone knew where they stood. Or, quite possibly, knelt, with their hands on their head, waiting for the bullet that would end their life.

One of the greatest hypocrisies (and there are many) of the treatment of the Indians, as they were then called, in the American West is that the US Government and Army did not come right out from day one and say “we hate you, we have no use for you, there is no room for you in this new world we are going to force upon this land, and we are going to kill you all, or at worst, shove you all into ghettos.” Had they done so, it would not in any way have lessened the horror of what happened, but at least the tribes would have known what to expect. When Hitler had the Jews herded into ghettos prior to being transported to the camps, it’s a safe bet that none of them thought they would be allowed live. They knew where they stood. But with the Indians, it was so much more insidious and underhand.

Much of this, of course, came from political exigency. As settlers moved West and, to be blunt, wanted the lands that belonged to the Indian tribes - had been promised them by their government - the president and his cabinet had to renege on their promises, or part of them, pushing back the demarcation line which was supposed to encompass what were to be known as Indian Territory, until finally the borders of that land shrunk to a few reservations, while the white people trampled all over the Indians’ sacred ancestral hunting grounds. As in all things, the white man came first. It had been so from the time when the first white man had stepped onto the land that was later to be known as America, and imposed his and his country’s, and his race’s values upon what he saw as “savages”. White America wasn’t really that bothered about imposing values on these savages, they just wanted their lands, and if they had to kill a few million of them, well they had no problem with that.

The pages of the history of the American west - but mostly, not the silver screens of movie theatres, for obvious reasons - are filled with massacre after massacre of Indian tribes, and not just the men. The US Cavalry seems in general to have made little to no distinction between warriors or braves, and their women and children. All were cut down with the same lack of human compassion or regard, families slaughtered in bloodbaths the likes of which we would not see again till World War I, and which had been recently witnessed through the dripping, scarlet eye of the Civil War. Nobody cried over these innocents, at least, nobody that counted. Often there was nobody left of the tribe to mourn them, as they were all wiped out together. And these were no orderly military campaigns either; at best, Indians could muster rifles, but usually defended themselves (assuming they got the chance to; many of these were sneak attacks, which would have been loudly proclaimed as underhand and cowardly in the US Senate had they been carried out by the Indians) with axes, bows and arrows and spears. The US Army had artillery, rifles and the precursor of the dread of the trenches, the machine gun, in the Gatling gun, which could kill many men at a distance like some chattering goblin of destruction.

There was no comparison, and no chance for the Indians, even assuming they knew what was coming and could prepare for it. Fire, too, was used by the white man, as the Indians almost to a man lived in hide-covered tepees or wigwams, hungrily devoured by flames in an instant, and like the thatched cottages and shacks callously burned by the Normans and others down through history, one man with a single torch could realistically destroy an entire settlement, camp or village in moments. Once the panicked denizens rushed out, seeking safety, weapon fire would cut them down, or else brave cavalrymen would ride in and slice them to pieces, taking, it should be noted, scalps often as trophies, emulating the practice of some of the more warlike tribes.

Sadly, but a single example of such a massacre, but so rooted in not even misunderstanding, but a sense of entitlement, arrogance and pure good-old-fashioned violence in response to a reasonable request was the account below that I feel it incumbent upon me to relate it. To place it in context, it came as the result of a horse-race was disputed by the Navajo tribe, who believed - and it seems correctly - that they were cheated. Approaching the fort to air their grievances, one man was shot and then all hell broke loose. The below report is by Captain Nicholas Hodt of the US Army.

“The Navahos, squaws, and children ran in all directions and were shot and bayoneted. I succeeded in forming about twenty men .... I then marched out to the east side of the post; there I saw a soldier murdering two little children and a woman. I hallooed immediately to the soldier to stop. He looked up, but did not obey my order. I ran up as quick as I could, but could not get there soon enough to prevent him from killing the two innocent children and wounding severely the squaw. I ordered his belts to be taken off and taken prisoner to the post .... Meanwhile the colonel had given orders to the officer of the day to have the artillery [mountain howitzers] brought out to open upon the Indians. The sergeant in charge of the mountain howitzers pretended not to understand the order given, for he considered it as an unlawful order; but being cursed by the officer of the day, and threatened, he had to execute the order or else get himself in trouble. The Indians scattered all over the valley below the post, attacked the post herd, wounded the Mexican herder, but did not succeed in getting any stock; also attacked the expressman some ten miles from the post, took his horse and mail-bag and wounded him in the arm. After the massacre there were no more Indians to be seen about the post with the exception of a few squaws, favorites of the officers. The commanding officer endeavored to make peace again with the Navahos by sending some of the favorite squaws to talk with the chiefs; but the only satisfaction the squaws received was a good flogging.”

Now consider that the above massacre - you can’t really call it anything else - was sparked by one of the men asking for reparations, for justice, not to be cheated, and when the gate of the fort was rudely slammed in his face, trying to force entry. He was immediately shot. I mean, it’s somewhat overkill, isn’t it? And then it led to a total slaughter as what I suppose cops today in America might call an “unlawful gathering” were treated with the full, terrible and repressive hand of the law of the West, American law, white law. I suppose that could as easily have been a bunch of black people today.

Of course, there are worse, some famous, some not, many hushed up, excused and in some cases even gloried in, but the one above does serve to show just how little the white soldiers and their commanding officers thought of these people who mistakenly believed they were dealing with friends, kindred spirits, reasonable men. While in my

History of America journal I can and do go on at length about the various tribes, their customs, deeds, achievements, daily lives, this is all before we white men set foot on the continent, and since then, the story of the American Indian, or the Native American, whichever you prefer, has been slowly and then with increasing speed charging down a hill like a stampede of wild buffalo, heading for extinction. In a very real way, the appearance of the white man in America can be likened to the unwelcome intrusion of Satan into the Garden of Eden. Of course, Indians would not make that comparison as they’re not Christian, which just shows how most allegories don’t hold up very well to close examination. But it’s certainly true to say that the second half of the nineteenth century sounded the death knell of the freedom of the Red Man, the end of his ownership or guardianship of the plains, the severe dwindling of the buffalo and the first chapter of his own personal version of Paradise Lost.

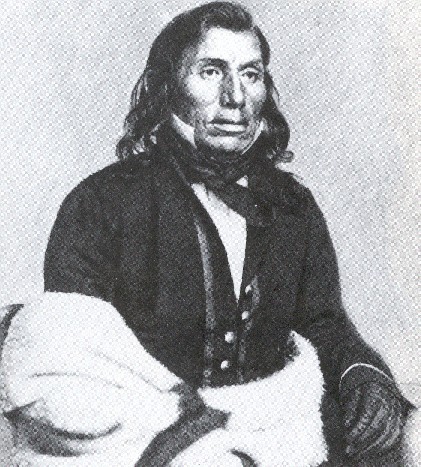

While there are huge names in Native American lore, giants who stand like titans astride the history of the West, so compelling and memorable that they cannot be stricken from the record or buried with the dead, men who fought against the might of the white man’s army - and in some cases, at least temporarily, won - these people will be dealt with where they deserve to be, in the annals of those who contributed to the history of the West. They can’t be relegated to a section on Indians, these names that call to us down through almost two hundred years and remind us of our sins. Red Cloud. Tecumseh. Crazy Horse. Geronimo. And of course, Sitting Bull. These men’s resistance to the white ethnic cleansing ring loudly through the lore of the West, and should make us shrink from their courage and their determination to preserve their people, even if this proved to be a hopeless task.

No. Here, in this section, I want to look at some of the lesser-known names, those who have been forgotten by or erased from history. The ones who stood up and said no, the ones who gave their lives to save their fellows and their families, the ones who refused to move off their land, granted to them by their gods and the spirits of their ancestors. There are many, many stories of heroism and bravery, rugged determination and stubborn resistance buried in the bones of the mountains and the soil of the earth, drowned in the rivers and looking down from the hot skies, and while we can’t bring them back, they should not be allowed to be forgotten.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode