As the new decade bore down upon the world and the dark clouds of war began to gather, though not yet for America, Warner Bros set about mounting a serious challenge to Disney, a task it has to be said they achieved. The creation of the very first

Looney Tunes character, Porky Pig, was followed in relatively rapid succession by names which would reverberate down the annals of animation and cartoon history: Elmer Fudd, Daffy Duck, Sylvester and Bugs Bunny. For almost forty years

Looney Tunes and its companion series

Merrie Melodies would thrill and make children laugh in cinemas, and later on television, and even today these cartoons are still shown and appreciated, as much by the adults who grew up on them as by the kids of today. Some cartoons are timeless, and some subjects are evergreen - one character getting constantly hurt by another, traps, schemes, wacky machines, hunger, chases, territorialism and all the other things that go up to make relationships between cartoon characters kept

Looney Tunes and

Merrie Melodies fresh, even if in general, the same basic plot was being rehashed each time.

Wile E. Coyote employs more and more zany and unreliable methods to catch Roadrunner, methods which invariably fail. Sylvester tries in vain to eat Tweety-Pie. Tom chases Jerry. Bugs outsmarts the hunter, and often Daffy too. Speedy Gonzales is the fastest mouse in the south, and Yosemite Sam is the fastest gun in the West (and also possesses the largest moustache and biggest hat). Foghorn Leghorn cannot convince that kid that he is a sparrowhawk, not a chickenhawk, and Porky still has his endearing stammer.

Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies never really broke with what was a successful formula. If Wile E. Coyote bought something from ACME we knew it would end up turning against him. If Tom caught Jerry we knew the mouse would get away. It wasn’t really new stuff that attracted us, it was the repetition of the old. I mean, who

didn’t laugh every time that cloud of dust came up from the desert floor as the luckless coyote impacted it? A real case of, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it.

So Warner based their cartoons around the predictable, the expected and the familiar. Not the actual events, but you could tell how things were going to turn out at the end. The animation from the first was better than good, and would of course end up top-class, and unlike Disney, who would, for a long time, stick to having songs in their cartoons, Warner would have incidental music but usually no actual songs, except on odd occasions, like maybe if Bugs serenaded someone or Daffy was in a band or whatever. With

Looney Tunes (let’s just assume

Merrie Melodies is included in that; I’m tired of writing both) it was all about the zaniness of the cartoon, the illogical universe the characters inhabited, and their personalities. With Disney it was definitely more story-based, as their features tended to plunder old fairy tales -

Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Pinocchio etc - and also literature, as they tacked

Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan and the like. Story before personality, really, though that’s not to say they didn’t imbue their characters with personality. But can you really remember much about the prince in

Sleeping Beauty, or Wendy in

Peter Pan?

Looney Tunes characters would be known for their catchphrases and the things they did. Bugs nibbling a carrot asking “What’s up Doc?” or Daffy telling someone - usually the rabbit - they were despicable. Sylvester would exclaim “Suffering succotash!” (and we all wondered what the hell succotash was, though nobody really cared) and Speedy would cry “Yee hah! Yee Hah! Hondolay!” and streak off. The vast majority of

Looney Tunes’ anthros would have no clothes, and yet there was no suggestion of nudity. Foghorn Leghorn, Bugs, Daffy and Sylvester strode around as nature intended, and there were no irate telephone calls to the network. Others were dressed: Speedy wore a sombrero and Spanish garb, Porky wore a tweed suit, Elmer Fudd a hunting outfit, and of course Yosemite Sam was dressed as a cowboy. Often these disparate characters would star in their own cartoon solo, but often too they would meet or be paired up with others, most famously Bugs and Daffy, who seldom got on.

Tex Avery (1908 - 1980)

Tex Avery (1908 - 1980)

One of the most recognisable names in cartoons, and one of those who helped usher in the non-Disney part of the Golden Age of American Cartoons, Frederick Beans “Tex” Avery was of course as you would expect born in Texas, just outside of Austin. From such small acorns… Beginning his career as a lowly inker with Winkler Pictures, he was perhaps privileged to have worked on the early cartoons of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, but left Winkler to go to Universal Studios, again as an inker initially but soon his talent was recognised and rewarded, and he was the animator who worked on Oswald after production was moved to Universal. He also began his directing career here.

An office accident led to his losing the sight in one eye when one of his co-workers shot a paper clip his way via rubber band and, warned by another colleague to look out, he turned at the wrong time and the paper clip hit his eye. In 1935, unhappy with his wages, he began to let his standards slip, hoping to be fired. He was, and then moved to Leon Schlesinger’s studio, where he worked on the

Looney Tunes, which were at this time, and until 1940, in black and white still, and also

Merrie Melodies, which had been in Technicolor since 1935. Working with other directors, including Jack King and Friz Freleng, Avery had the use of four animators - Chuck Jones, Sid Sutherland, Bob Clampett and Virgil Ross, and they all moved into a new five-room bungalow at Warners when they outgrew the main studio. Due to its dilapidated condition and insect infestation, this became known as “Termite Terrace”.

Within his first year at Warners Avery had discounted the character meant to be the main one, Beans the Cat, in favour of Porky Pig, whom he redesigned the next year to be cuter and more cartoon-like. Reportedly a good boss to work for, Avery talked to his animators and often went to the lengths of explaining some of his ideas if they didn’t get them. He was always smiling and pleasant, and often lent his voice to some of the characters. He presided over the creation of Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny (though he did not like the name, preferring instead Jack E. Rabbit, but was overruled by the studio) and became a household name. In 1941 he left Warners to work at MGM, where he really came into his own, even creating some very

risque (for the time) cartoons such as Blitz Wolf, which parodied the

Three Little Pigs fairy tale with Adolf Hitler, and

Red Hot Riding Hood, which you can probably guess at. All told, he worked at MGM till 1953, with one year off in 1950, the longest he had worked at any studio.

Avery later became quite depressed and withdrawn when his son committed suicide, and he moved into television commercial cartoons, but never seemed happy in the medium. He died in 1980 of cancer, remembered as one of the men who made cartoons into what they are today.

Friz Freleng (1905 - 1995)

Friz Freleng (1905 - 1995)

Some of the names of animator, directors and producers just stuck in my mind as a kid a) because they were so prominent in the opening credits and b) they were weird to me. Quimby, Avery, and this guy. I always thought it was odd that he wasn’t Fritz Freleng, but Friz. His actual name was Isadore, and he was from the same town which could almost be called Cartoon City, Kansas City in Missouri, from which had already sprung Ub Iwerks, Rudolph Ising, Hugh Harman and Carmen Maxwell. Oh yeah, and some guy called Walt. After he moved to Hollywood, Disney invited the Kansas City mob to join him at his new studio, and Freleng followed the others in 1927. As with so many of Disney’s animators though, Freleng found the way he was treated unconducive to remaining and instead joined Ising and Harman on the Bokso cartoons, but worried these might not be successful he headed to New York where he worked on Krazy Kat for Charles Mintz.

He returned to take up a position as director for Leon Schlesinger on the

Looney Tunes, and was instrumental in bringing Porky Pig to life. He had a short spell with MGM but returned to Warners in 1939. He was heavily involved in the development of Sylvester and Tweety Pie, Yosemite Sam and Speedy Gonzales. During his time he won four Academy Awards and was nominated for six more. Later he would move to Hanna-Barbera and with David DePatie create the iconic Pink Panther, among others. He died in 1995, perhaps one of the few animators not to die of cancer, but of natural causes. He was 89 years old.

Bob Clampett (1913 - 1984)

Bob Clampett (1913 - 1984)

Perhaps a less well-known name, maybe because he only remained in cartoons till 1945, Bob Clampett nevertheless was important to the creation and development of some of Warners

Looney Tunes best-known characters, such as Sylvester and Tweety, Porky Pig and Daffy Duck. One of the only animators to be born in California, and perhaps one of the only Irish-American ones, his parents being immigrants from County Tipperary, Clampett lived next door to Charlie Chaplin and knew Harold Lloyd, and was a child prodigy, already excellent at art by age five. He was involved with Walt Disney when, on the basis of a sketch he made at the cinema, his aunt created a line of Mickey Mouse dolls to sell, with Disney’s approval.

At age seventeen, Clampett joined Ising and Harman on Schlesinger’s Merry Melodies, and worked under Friz Freleng, who took him under his wing. In 1934 he submitted a drawing of a pig to Schlesinger, who was looking for a new character, and so Porky Pig was born. Later he moved into the infamous “Termite Terrace” under Tex Avery and worked with his animators, and in 1937 when Avery created Daffy Duck it was Clampett who animated him. Clampett was largely responsible for the increasingly surreal universe the

Looney Tunes characters inhabited, as he threw the rule book out the window. After setting fire to it. His style went down so well at cinemas that Schlesinger instructed his other animators to follow suit, leading to Warners becoming the standard for crazy, zany, off-the-charts cartoons, with things like characters running off the page, being rubbed out, finding themselves in black or white nothingness, and on more than one occasion, directly addressing the animator. Roadrunner’s weird non-logic world came from this idea too, the likes of train tunnels drawn on walls by Wile E. Coyote becoming passable for Roadrunner but not for him.

Clampett left Warners in 1946 and though he worked for a short time for Charles Mintz’s

Screen Gems, he soon turned his attention to puppets, which would win him three Emmys for the show

Time for Beany, and then took to the lecture circuit, sharing his experience and expertise with college students and would-be animators. He died in 1984 of a heart attack. His genius may have come at a price though; his colleagues did not have much good to say about him, some of them claiming he took credit for their ideas, others annoyed at the way he and only he seemed able to break the rules at Warner. He is on record claiming creation of both Bugs Bunny and Yosemite Sam, and Daffy Duck. I suppose it depends on who you decide to believe; a friend of Clampett’s maintains it was all a smear campaign by Chuck Jones, who didn’t like Clampett.

Chuck Jones (1912 - 2002)

Chuck Jones (1912 - 2002)

Another name we would see in my day written large at the start of our favourite cartoons, Chuck Jones was another Warners animator, who could be said to have inherited his artistic ability from his father, though not really. Charles Adam Jones was no artist, but a businessman, however he supplied his children regularly with previously-imprinted stationery as each venture failed, giving them all an interest in drawing. Chuck worked first for Ub Iwerks as a cel washer, then a painter, and so on up the ladder until he was taken on as an assistant animator by Leon Schlesinger on the closure of Iwerks’s studio in 1933. Two years later he was promoted to assistant animator and moved into “Termite Terrace” along with Tex Avery, Sid Sutherland, Virgil Ross and Bob Clampett.

Truth to tell, Jones did not get on well at Schlesinger’s studio, patterning his creations more on the Disney principle and being seen as “just not funny”. Schlesinger did in fact want to fire him but could not find a replacement; his involvement in attempting to unionise the studio would not have done much to mollify his boss either. The two butted heads and this led to a short strike at the studio, led by Jones, and in turn leading to the reluctant acceptance of defeat by Schelesinger as the union was established at his studio. During World War II Jones worked with Dr. Seuss, otherwise known as Theodor Geisel, on army educational cartoons called the

Private Snafu series. He would work with him again after the war, particularly on

How the Grinch Stole Christmas in 1966.

During the short closure of Warners in 1953 he moved to Disney, where he worked on the feature film

Sleeping Beauty, though he received no credit for his work, then rejoined Warner when they reopened. There, his most famous creations were Pepe Le Pew, Marvin the Martian and the iconic Wile E. Coyote and RoadRunner. In 1963, when Warners closed down for good, he set up his own studio but this was quickly (within a year) taken over by MGM, and he found himself working on “sanitising” (removing the content seen as objectionable, read, racist) the theatrical Tom and Jerry cartoons for distribution to the new television medium. In 1975 he wrote to Tex Avery, accusing Bob Clampett of stealing his ideas and those of other animators, and taking credit for work that was not his.

Jones was nominated for two Academy Awards and won two more, including an honorary Lifetime Achievement Award, for

"the creation of classic cartoons and cartoon characters whose animated lives have brought joy to our real ones for more than half a century." He died in 2002 of heart failure.

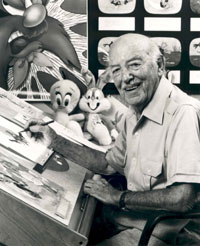

Mel Blanc (1908 - 1989)

Mel Blanc (1908 - 1989)

Quite rightly called “the man of a thousand voices”, Mel Blanc was the one who brought our favourite cartoon characters to life by giving them a voice. Chuck Jones, Tex Avery, Bob Clampett and the rest could draw them and direct them, but they were silent until Blanc spoke for them. His most famous voice is of course that of the wisecracking rabbit Bugs Bunny, but in his time he also voiced Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Barney Rubble, Speedy Gonzales, Elmer Fudd, Pepe Le Pew, Yosemite Sam, Marvin the Martian, Tweety Pie, Sylvester, Foghorn Leghorn, Secret Squirrel, Captain Caveman and many others too numerous to list in this short article.

Always interested in utilising his voice, and changing his name from its original Blank to Blanc because a teacher had told him rather callously that his surname was appropriate, as he would amount to nothing, Blanc first worked on radio, starting at age 19 and finding a place on the popular

Jack Benny Program in 1935, remaining a regular on the show until it ended twenty years later. His popularity on the show led to him having one of his own, which ran for a year up to 1947. It was however with Warner Bros - originally Leon Schlesinger’s studio - that he found his greatest fame, voicing most of the cartoon characters being created there, as detailed above. Soon he was one of the most recognisable voices in America, and indeed the world. He also worked with Chuck Jones and Dr. Seuss during the war, creating the voice for the hapless

Private Snafu.

Later in his career he would go on to provide voices for characters for the Hanna-Barbera Studio, including Wally Gator and Barney Rubble, and in 1961 he was involved in a serious car accident, only reached in the coma into which he had fallen by the doctors addressing not him, but his cartoon characters. He in fact provided the voice for Barney for many episodes of

The Flintstones from hospital, lying on his back with the other cast members gathered around his bed. He set up his own production company and, like Clampett, got on the college lecture circuit.

Mel Blanc died in 1989 from complications brought on by emphysema, and coronary artery disease. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame as does Bugs Bunny, his most famous voice. His headstone, at his request, contains the epitaph “That’s all folks!”

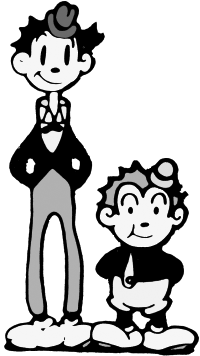

Stand by for the usual by-now-standard high jinks with the piano, and yes, there are the Marx Brothers emerging from it. Sigh. Didn’t Ub Iwerks already do this with Flip the Frog? More, I assume, famous Hollywood stars of the thirties being caricatured, though I don’t recognise any. Okay, I recognise Laurel and Hardy, and maybe that’s Charlie Chaplin?

Stand by for the usual by-now-standard high jinks with the piano, and yes, there are the Marx Brothers emerging from it. Sigh. Didn’t Ub Iwerks already do this with Flip the Frog? More, I assume, famous Hollywood stars of the thirties being caricatured, though I don’t recognise any. Okay, I recognise Laurel and Hardy, and maybe that’s Charlie Chaplin?

Linear Mode

Linear Mode