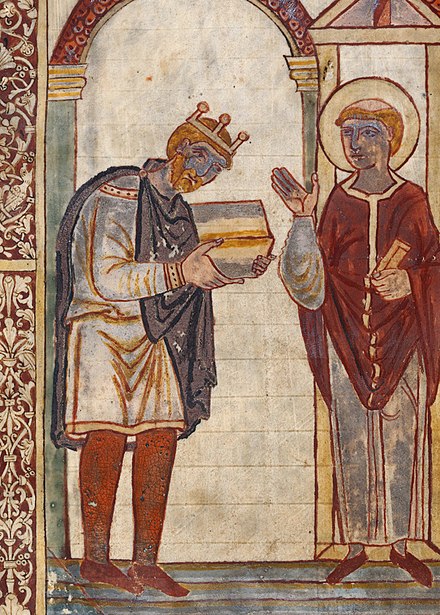

Edward the Elder (874 - 924)

Edward the Elder (874 - 924)

On the death of Alfred his son Edward the Elder ascended to the throne, but not unopposed. As is often the case when the king dies, there was another claimant to the kingship, and this was Aethelwold, the son of Alfred’s older brother Aethelred, who claimed he had been too young at the time of his father’s death to take the throne, which had passed to Alfred as next in line in the succession, but that it was his birthright. And he intended to assert that birthright. And how did nobles in tenth-century England assert their birthright when challenged? By sitting down and talking things over calmly, of course, putting all points of view on the… yeah. Right.

Aethelwold raised a small army and seized Wimborne, in Dorset, where his father was buried. He then took the surrounding area and waited for Edward to respond. When he did, Aethelwold refused to engage him but instead rode to York to seek support from the Vikings still in control there. They crowned him king, while Edward was crowned in Kingston-Upon -Thames in 900. It wasn’t the last time England would have two competing kings. Aethelwold began a campaign against Essex and Mercia, trying to weaken his cousin’s powerbase, but he came unstuck at the Battle of the Holme, in which he was killed. End of challenge.

Alfred had been proclaimed as the first “King of the Anglo-Saxons”, and so Edward also took this title when his claim was established beyond doubt and supported. Alliances were further forged between his England and Francia (with the marriage of his daughter to the king, the hilariously-named Charles the Simple) and Germany, where another daughter was wed to Otto, the king and later Holy Roman Emperor. Alfred had proven that he was good at developing networks with his burh line of defences, now his son extended those networks into a socio-political one, linking three great countries and tightening the bonds of interdependency of each on the other. Edward then set about retaking the area of England currently under Danelaw, defeating the Vikings in the Battle of Tettenhall in 910, so comprehensively in fact that all territories south of the Humber were at his mercy and Edward was able to take most of East Anglia and Mercia including Derby, Lincoln, Stamford, Nottingham and Leicester.

The next year, on the death of the ruler of Mercia, Aethelred, Edward moved in on London and Oxford, and, with the help of Aethelred’s widow Aethelflaed, began to fortify Mercia against incursions by the Danes. One of the last major Viking attacks was in 914, when a force from Brittany invaded South Wales, but they were pushed back. By 918 he had defeated all opposition and basically ruled almost all of England. Those Vikings left in the country submitted to his authority.

Soon after he took the throne, Edward obeyed his late father’s wish and began to have built the new abbey at Winchester which would be called New Minster, to which the dead king’s remains were transferred, until the arrival of the Normans. Edward continued his father’s policy of trying to educate his people - in English - and in passing new laws, one of which led to a process which persisted through England well into the medieval era.

Trial by Ordeal

From what I can see, two things characterised the idea of Trial by Ordeal: one, that no man was considered innocent until proven guilty (in fact, possibly the opposite) and two, that God was literally expected to be the star witness. Sounds weird huh? Well, it was, but the thinking seems to have been that God would not allow the guilty to escape, and so would send some sign that they were guilty. The most simple and basic - and slightly understandable - version was

Trial by Combat, which surely needs no explanation. However, not only were the two parties in the dispute allowed to fight each other, they could also nominate a champion to fight in their stead. Seems a little unfair. What if you’re innocent, but your opponent chooses well-known pillar of the community (literally; he once held up a post that was bringing down the roof of the community shelter!) Harry the Glass-Eater, built like yon brick privy and with a head like a bullet? He’s going to win, isn’t he, and then the law says you’re guilty. So that’s literally a case of only the strong (or clever) survive.

What were the conditions or criteria for choosing a champion? No idea; I can’t find any. But over time this practice, until it was done away with, seems to have evolved into the later modern idea of a duel. That was only trial by combat though. You also had

trial by fire, in which the accused had to walk across burning coals, and if innocent would either receive no burns or God would heal them rapidly (three days was usually the time period allowed;

trial by water, both hot and cold. Trial by hot water involved picking some object up out of a cauldron of boiling water, while trial by cold water seems to have been concerned with the accused man throwing himself in a river and if he survived he was innocent. Then there was

trial by cross, not nearly as brutal as it sounds. The accuser and the accused would stand on either side of a cross and stretch out their arms. The first to drop his arms was deemed to have lost, so basically an early version of using the stress position.

There was also

trial by ingestion, where an accused person was given blessed dry bread and cheese, and if they choked were guilty, and trial by poison. Wait, what? No, that’s right: the person accused would be given a poisoned bean to swallow and if they puked it back up they were cleared, if they died, well, they were guilty and deserved to die. Stupid, yes, but not as pointless as

trial by turf. No, I’m

not having you on and no it was

not an Irish custom, you racist, but in fact an Icelandic one. Not very complicated: the accused walked under a bale of turf and if it fell on him he was guilty. Possibly where the phrase “turfed out” comes from? Could it be that illegal wagering on such an event led to turf accountants? I’ll get me coat.

No, I won’t. I have much more to bore you with. But it should be noted that not every facet above of this trial by ordeal was practiced in England, just that it sort of began there to be seen as a legitimate practice and hung on really into about the sixteenth century, though rarely used by then. Of course, a version of it figured in the witchcraft trials of the tenth century. But it was being more or less phased out by about the thirteenth.

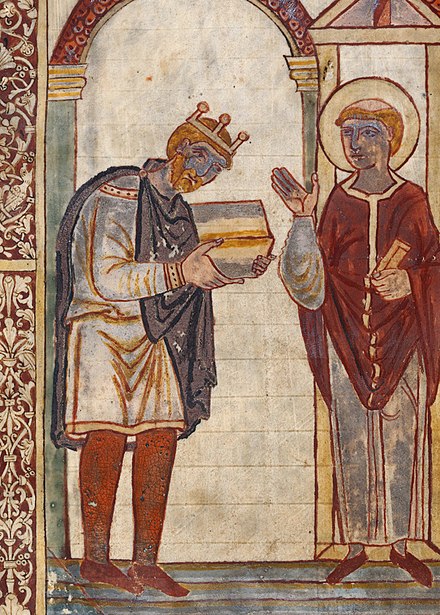

Aethelstan (894 - 939)

Aethelstan (894 - 939)

Edward died in 924 at his estate, shortly after having put down a revolt at Chester, and was buried alongside his father Alfred in the New Minster. He was succeeded by his son, Aethelstan, who, even more than Alfred and certainly more than Edward, has been recognised by historians as the first true King of England. Like his father though he did not come to the throne unopposed, as many believed his brother Aelfward was next in line. However he died only ten days after Edward, which kind of made the situation moot. Rather oddly perhaps for a king, who were usually obsessed with passing on their power, maintaining or creating a dynasty, which naturally requires progeny, Aethelstan took a vow never to marry or have children. Al Bundy would have respected and envied him! But it didn’t help the line of royal succession, of which more later.

Nonetheless, the coronation of Aethelstan is recognised as the first time an English monarch wore a crown, instead of the usual helmet used, which certainly lends weight to the argument (not really an argument; for once all these usually squabbling historians agree) that he can be said to have been the very first proper King of England. Winchester hated him though, its support behind the late Aethelward and seeing him as a bastard; they even plotted to blind him, this certainly a crime but not as serious a matter as murder (sure I only blinded him, Yer Honour. The bastard had it coming. Yeah, Doubt it would go far as a plea for clemency) and the Bishop of Winchester returned all RSVPs unopened when he was invited to ceremonies. He didn’t even bother going to the coronation. I bet he wasn’t missed.

The death of Athelstan’s remaining step-brother, Edwin, who perished at sea while possibly legging it from a failed coup attempt in 933 helped bring Winchester into line. With nobody left to challenge the king they more or less shrugged and said “Fu

ck it, he’ll do.” Not like they had any choice. Kings are of course notorious for failing to keep their word, and when Aethelstan promised Sitric, king of the last remaining Viking strongholds, York, that he would not invade his kingdom, sealing the deal with the marriage of his daughter to the Viking king, he seized his chance once old Sitric was knocking on the door of Valhalla requesting entrance and bearing a long scroll, no doubt, of his valourous achievements. York was easily taken, and when Northumbria had to submit too, Aethelsan became the first southern king to rule the northern kingdoms (yes yes, go on, you know you want to say it: King in the North! There; feel better now? Can we continue?) and in effect became the first King of England.

He ventured over the border in 934 to make war upon Scotland, though there are no actual accounts of what he did up there. He was accompanied by four Welsh kings, and while this might not be the first time Wales attacked (or participated in an attack against) Scotland, it’s the first time I’ve read of them venturing that far north. At any rate, the campaign did not last long and was over by September, having begun in May. His next conflict though was a pretty major one, and even if we have only sketchy details of what went on, it has been acknowledged as one of the most significant battles in the history of what was becoming England.

Olaf Guthfrithson, Viking king of Dublin, having secured his position by that ancient Norse expedient of slaughtering all his foes, decided the time had come to reassert his control over what had been Danelaw and sailed to England in 937, intent on taking York. The Scottish king, Constantine, probably smarting from his earlier defeat, joined up with him and they met at the Battle of Brunanburh, which nobody can seem to decide a location for, much less pronounce. It’s probably not that important. What is important is that Aethelstan kicked Viking arse and Olaf retreated, limping back to Ireland for a well-earned Guinness or ten, while Constantine f

ucked off back across the border, one son less. It was a great victory for Aethelstan and ensured his enemies, both foreign and domestic, would think twice before taking him on again.

Under his rule, the emerging England (land of the Angles, or Angle-Land) began to see the growth of a true government, with officials such as ealdormen at the top (often ex-earls or leaders from the Danelaw) who administered in the name of the king, then reeves, landowners who seem to have their closest contemporary in mayors or burghers, ruling over a town or estate in the king’s name, and the witan, or royal council, which was not set in any one place but could be convened by the king, a sort of travelling committee. He seems to have had a particular thing about theft, prescribing in his laws the death penalty for anyone over the age of twelve years caught stealing more than eightpence. Why twelve years, and why eightpence? I have no idea, but it seems that Aethelstan equated robbery with a breakdown of the laws of society, and he may, following his predecessors’ devout views, have considered that since it was a literal breaking of one of the Ten Commandments, that it deserved harsher punishment.

Aethelstan devised the system of tithing, which is nothing to do with giving away a tenth of what you earned to the Church, as happened almost a millennium later in Ireland, but was in fact a subdivision of a parish or manor. Tithingmen appear to have been the very first rudimentary police force in England, or at least a precursor to the Watch. Ten men would be sworn to ensure to keep the peace in a particular area, and would be responsible for anyone who broke the law, sort of in effect standing guarantor and vouching for them I guess. It’s a little complicated and I don’t quite understand it, so here’s what Wiki tells us:

“The term originated in the 10th century, when a tithing meant the households in an area comprising ten hides. The heads of each of those households were referred to as tithingmen; historically they were assumed to all be males, and older than 12 (an adult, in the context of the time). Each tithingman was individually responsible for the actions and behaviour of all the members of the tithing, by a system known as frankpledge. If a person accused of a crime was not forthcoming, his tithing was fined; if he was not part of the frankpledge, the whole town was subject to the fine.”

Yeah, still don’t get it really.

In Aethelstan’s time, and long after, there was no such thing as a separation of Church and State, the two intermeshed and bound together, and who could truly say where the real power lay? A king who lost or had not the backing of the bishops might not last long, while represtantives of the Church were chosen by Rome, where the Pope had very much a veto, and to go against him would not be good for any king. People of course were almost fanatically religious, obedience of the Church and obedience to their king one and the same in the minds of most folk, and heretics would be mercilessly dealt with, as we saw with the Druids and indeed the original Britons themselves, to say nothing of the Picts to the north. At that time, it was probably impossible to even contemplate the existence of one without the other - the Church supported and gave legitimacy to the Crown, and the Crown ensured the Church was revered and obeyed as a matter of law. It wasn’t of course until six hundred years or so later that this all changed when Henry VIII couldn’t get his way.

Aethelstan was free to appoint bishops to whichever diocese he preferred, though it seems likely that he would have to secure the permission, or at least agreement of the Pope for these appointments, and he certainly would not be able to ordain any new ones. That power rested solely with Rome. He also fostered closer relations with other countries, including Germany, the spiritual birthplace of the Saxons who now ruled England, and of whom he was a descendant. In a move which will seem insulting to us today, but was probably common practice in the tenth century, and perhaps for some time beyond, he sent one of his bishops with two of his half-sisters to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Otto, basically inviting him to take his pick, choose one for his wife. He probably didn’t care which, and I doubt the woman was allowed any say in the matter: this was all about building alliances and securing territories.

Aethelstan was the first real English king to establish the prestige and power of the young country outside of its own borders, his and his forebears’ victories against the Vikings making England quite the power in the west, and if there’s one thing kings and emperors and princes and dukes are drawn to it’s power. Aethelstan married off many of his sisters and half-sisters to foreign nobility, as we have seen above, and created strong bonds both military and political with countries such as France and Germany. He was also popular in Norway, where he helped Hakon Haradlsson reclaim his throne, and he is, probably more than any other English king before or since, responsible for the mixing of the royal bloodlines, and the eventual close relationship between England and Germany, as the latter assumed the English throne in the centuries to come.

When he died in 939, Aethelstan chose not to follow the example of Alfred and Edward, his father and grandfather, by being buried at Winchester, but chose instead to have his remains laid to rest in Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire, the only Saxon king to be buried there.

Unfortunately, all the good work he had done driving out the Vikings came undone after his death. York, rising again perhaps in confidence now that the king was dead, crowned Olaf Guthfrithson, who you may remember had been sent running defeated back to Dublin, and he immediately invaded the east midlands, as the Viking threat, thought subdued but really only brooding and waiting across the sea in Ireland, reared its head again.

Hybrid Mode

Hybrid Mode